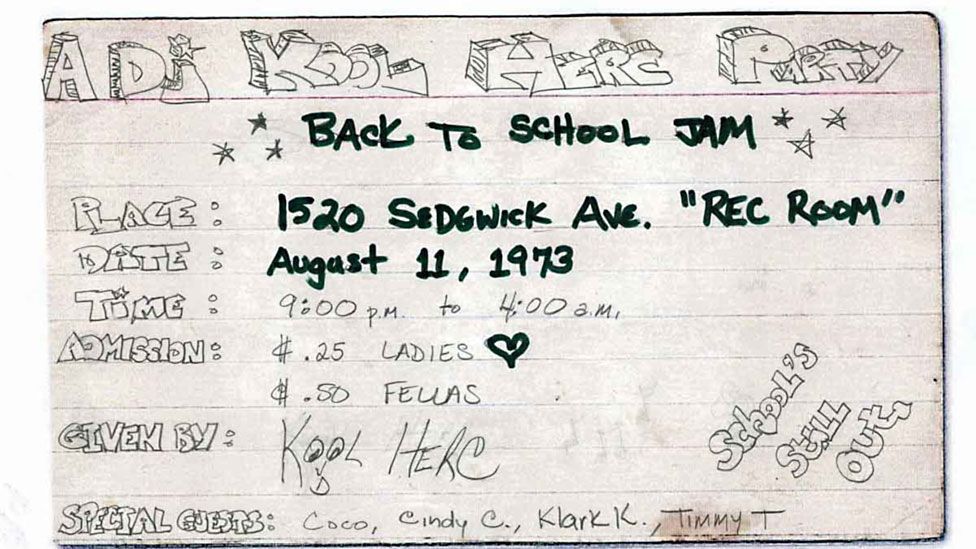

On a hot August night in 1973, Clive Campbell, known as DJ Kool Herc, and his sister Cindy put on a “back-to-school jam” in the recreation room of their apartment block at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in New York City’s West Bronx. Entrance cost 25c for “ladies” and 50c for “fellas”.

The party wasn’t special for its size – the rec room could only hold a few hundred people. Its venue and location weren’t particularly auspicious. Yet it marked a turning point, a spark that would ignite an international movement that is still here today.

More like this:

– The forgotten ‘godfathers’ of hip-hop

– Eight people who rapped long before hip-hop

– How hip-hop is saving a dying language

The legend is a simple one – but the factors leading to the creation of a hip-hop culture were a fusion of social, musical and political influences as diverse and complex as the sound itself.

The original invitation for Cindy Campbell and DJ Kool Herc’s ‘back to school jam on 11 August, 1973 (Credit: Getty Images)

In his award-winning 2005 book, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, the journalist and academic Jeff Chang locates the foundations of hip-hop in the social policies of “urban renewal” pioneered by the city planner Robert Moses and the “benign neglect” of US President Nixon’s administration. The Moses-conceived building of New York’s Cross Bronx Expressway razed through many of the city’s ethnic neighbourhoods, destroying homes and jobs and displacing poor black and Hispanic communities in veritable wastelands like East Brooklyn and the South Bronx, while the government turned a blind eye to those affected.

Completed in 1972, Robert Moses’s Cross Bronx Expressway tore through the South Bronx, destroying homes and shops, and contributing to the area’s decay (Credit: Getty Images)

“Hip-hop did not start as a political movement,” Chang tells BBC Culture. “There was no manifesto. The kids who started it were simply trying to find ways to pass the time, they were trying to have fun. But they grew up under the politics of abandonment and because of this, their pastimes contained the seeds for a kind of mass cultural renewal.”

Break with the past

Following the waning of gang wars and the FBI’s suppression of radical black groups in the late 1960s, the emergence of hip-hop in the early ’70s represented a profound shift. Rather than taking direct political action, a new generation was expressing itself through DJing, MCing, b-boying/b-girling (breakdancing), and graffiti, the “four elements” of hip-hop. Brooklyn-born artist Fab 5 Freddy, who is credited with bridging the gap between New York City’s music and visual art worlds, argued that the looping interactivity of the four elements proved hip-hop went beyond a purely musical or artistic movement – it was an entire culture.

Marcyliena Morgan, Ernest E Monrad professor of the Social Sciences and founding director of the Hip-Hop Archive at Harvard University, asserts the importance of celebrating the positive narratives generated by the hip-hop generation. “Hip-hoppers literally mapped onto the consciousness of the world a place and an identity for themselves as the originators of an exciting new art form,” she tells BBC Culture. “They created value out of races and places that had seemed to offer only devastation.”

Finding the breaks

Kool Herc, along with Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash, is known as one of the “three kings”, the “holy trinity” of the early days of hip-hop. But Herc’s story, insists Chang, is where it all started: “Without DJ Kool Herc, we wouldn’t be talking about [hip-hop] now… all around the world,” he says.

In the early 1970s, the b-boys and b-girls developed dance moves built around the music’s breakbeats. (Credit: Getty Images)

Clive Campbell was born in Jamaica in 1955, moved to New York in 1967, and picked up the nickname “Hercules”, (shortened to “Herc”) for his impressive stature. His father Keith had a diverse record collection, and as the technician for a local band – and importantly for Herc’s burgeoning DJ career – access to sound equipment. Herc began DJing at house parties, where he made some important technical innovations. He found a way to make his set-up the loudest around, using two turntables and a mixer to switch between records. Inspired by a youth spent watching rival sound systems in Kingston, Herc brought Jamaican culture with him to the Bronx – the booming bass and dub sound, and the custom of “toasting” or talking over records, which his friend Coke La Rock used to powerful effect at the Sedgwick Avenue party.

Even more importantly, Herc observed that the b-boys and b-girls were going wild for the instrumental breaks in the records, and he began searching for the tracks – and the breaks – to please the dancers. His most famous musical discoveries, Bongo Rock and Apache by The Incredible Bongo Band, were purely instrumental: the bongo and conga beats kept the crowd dancing for longer. It was a simple observation, but the creation of the “breakbeat” was one of the key innovations in contemporary dance music.

Such was the popularity of his block parties that by the end of 1973, Herc could no longer DJ in spaces as small as the Sedgwick Avenue rec room. He moved into bigger clubs and the Bronx’s Cedar Park, and for a few years – with his crew the Herculoids – was the main draw in the area’s music scene. But by 1977, his star had waned and other rival New York DJs, notably the South Bronx’s Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash, were waiting in the wings.

In 2007, Kool Herc was involved in a campaign to stop the 1520 Sedgwick Avenue block being sold to developers. The recreation room was officially recognised by NYC Housing Preservation as “the birthplace of hip-hop”. In 2023, DJ Kool Herc was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Creation myths

The story of hip-hop’s genesis is a legend as much shrouded in mythology as that of punk and the Sex Pistols’ gig at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester three years later. That gig has become legendary as the birth of post-punk, indie and the entire Manchester scene. Thousands have since claimed they were there – although the actual number that attended is better estimated at between 40 and 100. What makes these tales so important?

“Every culture needs a creation myth,” says Chang. “These stories tell us about the kinds of values we want to transmit. I think the story of Herc and Cindy’s party, in ways we perhaps don’t realise, speaks to the need for joy amidst turmoil, the power of creativity against destruction, the ‘started from the bottom’ ethic that youth will always find a way to express itself.”

In 2023, DJ Kool Herc (pictured in 2008) was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (Credit: Getty Images)

Remembering and preserving the legacy of 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, DJ Kool Herc and the night of 11 August 1973 are ways to keep these positive values alive. “The Bronx won the rights to DJ history through constant repetition of the first time DJ Kool Herc connected his sound system and mixed records,” says Morgan, arguing that hip-hop’s pioneers transformed “the land of the ghetto into the land of myth and the future.”

Jeff Chang agrees. For him, looking back to hip-hop’s early days is also a way of looking forward.

“I’m not a purist or a nostalgist,” he says. “But I believe in the values that have sustained hip-hop from the beginning: inclusion, recognition, creativity, and transformation. In the end, hip-hop is about teenagers, it’s about youth. And as long as they are taking those values forward, hip-hop won’t die.”

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.