Astronomers were surprised to see evidence of notoriously hard-to-detect elements like oxygen and nickel using observations of adolescent galaxies from the James Webb Telescope.

(CN) — Why do different galaxies look so different? Why do they have different temperatures and different shapes? What happens to them along the way to make them like that? And, perhaps most crucially, is there anything unique about our own galaxy, the Milky Way, that might explain why we’re here? Or is ours merely an average, run-of-the-mill galaxy?

New research published Monday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters takes a small step toward answering some of these intriguing questions about the universe.

“We don’t have a really good idea of what causes different galaxies to turn out differently,” said the paper’s lead author, Allison Strom, a professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern University. “We understand the broad strokes, but the actual physics of how that happens is hard to understand.”

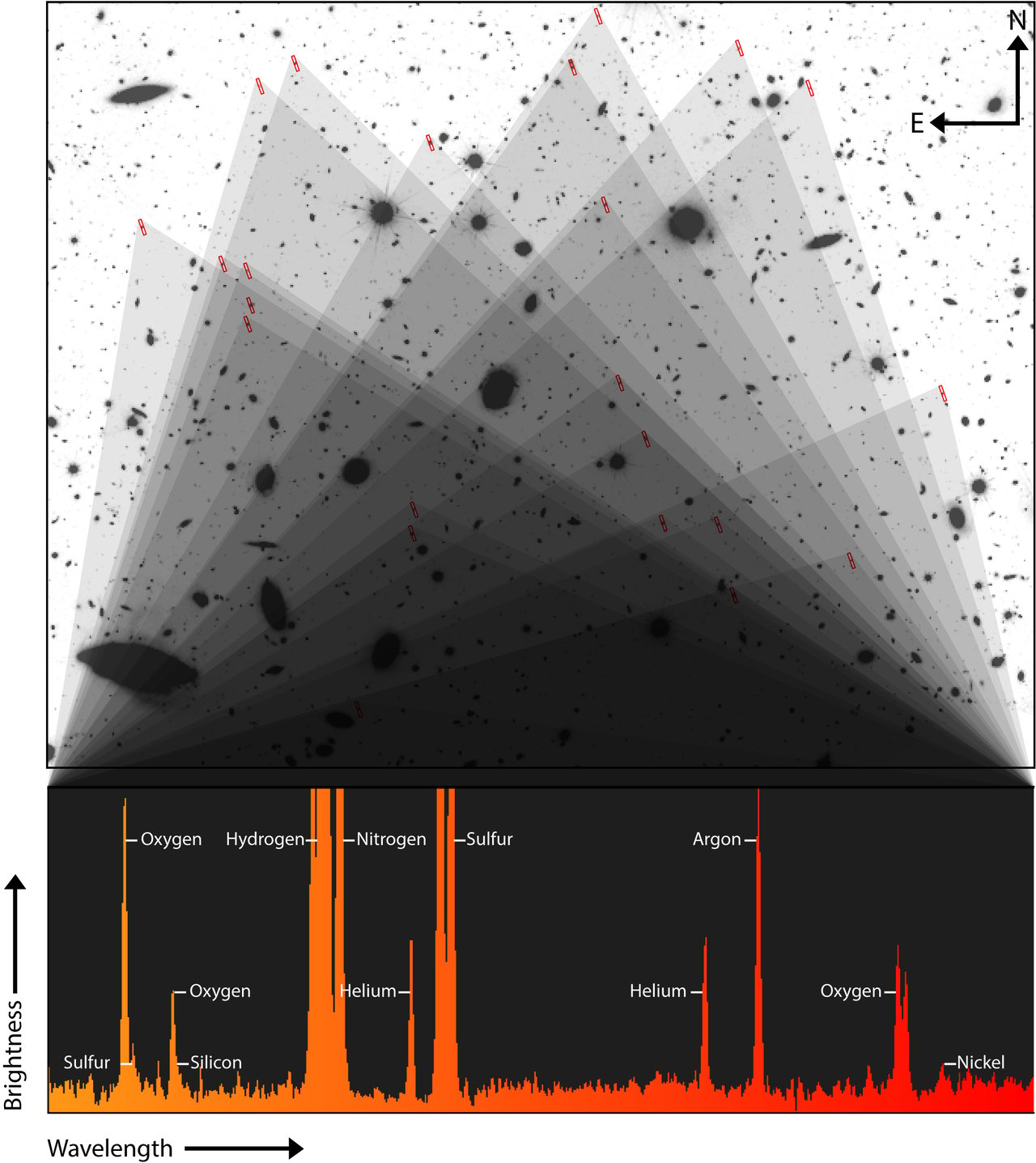

Strom and her team looked at the light spectrum from 23 distant galaxies, so far away that any light we see from them was emitted more than 10 billion years ago, two to three billion years after the Big Bang.

She calls them “teenage galaxies,” because of where they were in their stage of development when they emitted the light we’re only just now seeing. They weren’t young, per se — not in their “infancy” — but were in the midst of something of a growth spurt, forming many stars.

“It’s a very formative period for them,” said the paper’s co-author, Gwen Rudie, an astronomer at Carnegie Science. “And we actually think that a lot of the determining properties of what they’ll become probably get set during this period of time. But it’s something that we’re still trying to understand.”

The project uses light captured from the James Webb Telescope, launched in 2021 and currently orbiting around the sun. Astronomers were able to analyze the light spectra from the 23 different galaxies and isolate eight different chemical elements: oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, helium, sulfur, silicon, argon and, curiously, nickel, a metal heavier than even iron.

“We were really surprised” to see nickel, said Strom. “It’s very puzzling. We’re still not entirely sure what to make of it.” She added: “We think it might say something about how bright and how hot some of the stars are.”

The telescope picked up the light spectrum emitted by nickel in gas form, suggesting that the stars, along with the solar nurseries where stars are being formed in these teenage galaxies, are extremely incredibly hot. The teenage galaxies have fewer stars than, say, the Milky Way, but a greater number of hot stars.

The paper is the first in a planned series of seven or eight. The next one will look at the light spectra emitted by one single distant galaxy.

The project as a whole, helmed by Strom and Rudie, is dubbed CECILIA, standing for Chemical Evolution Constrained using Ionized Lines in Interstellar Aurorae survey. But the name is also an homage to Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, who was one of the first women to earn a Ph.D. in astronomy. Her 1925 doctoral thesis argued that the sun was made up primarily of hydrogen and helium, a groundbreaking work that cut against the conventional wisdom of the day, that the sun was like earth, made of rock, only glowing.

In order to use the James Webb Telescope for research, astronomers must submit an application and go through a competitive process. Strom and Rudie are part of the first round of researchers awarded time to work with the telescope, which uses infrared technology to see deep into space.

“Women are still underrepresented in astronomy,” said Rudie. “It’s rare to have two women leading something like this, still, to this day. And so we kind of wanted to celebrate that.”

Follow @hillelaron

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.