No history-defining look is complete without hair and make-up, a sentiment that London’s ‘Blitz Kids’ pioneered to the extreme during the late 1970s and 1980s. Spearheading this movement was Australian performance artist and fashion designer Leigh Bowery, who had a strictly enforced code of entrance for his short-lived but infamous Soho nightclub, Taboo: ‘Dress as if your life depends on it, or don’t bother.’

Yesterday (4 October 2024) Outlaws: Fashion Renegades of 80s London opened at the Fashion and Textile Museum in Bermondsey, paying tribute to Taboo and those who inhabited the world around it. Alongside Bowery, they included the likes of John Galliano, Pam Hogg, Stephen Jones and Judy Blame; musicians Steve Strange, Rusty Egan and Boy George; dancer and choreographer Michael Clark; and clubbing royalty Princess Julia, Philip Salon and Susanne Bartsch.

How Leigh Bowery and the Blitz Kids defined 1980s subculture with make-up

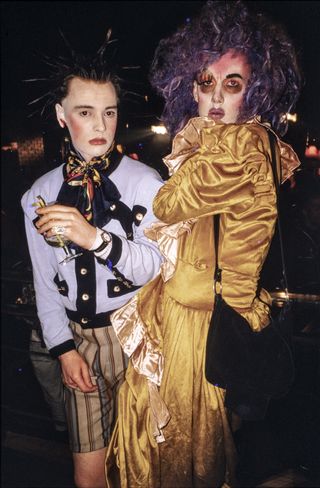

Trojan and Mark at Taboo, 1986

(Image credit: © Derek Ridgers courtesy of Unravel Productions)

Taboo was held in a dimly-lit corner of Leicester Square between 1985 and 1986. It followed in the footsteps of Covent Garden’s Blitz Club, where the New Romantics and Blitz Kids originated.

The club’s name was particularly ironic, considering that absolutely nothing that went on inside was considered as such, with Bowery injecting an intoxicating blend of avant-garde sleaze, sex and chaos into the space. His rule for loud, all-out looks was enforced by the notorious doorman Mark Vaultier, who would hold up a mirror to those vying for entrance and ask: ‘Would you let you in?’

‘Dress as if your life depends on it, or don’t bother.’

Leigh Bowery

Gaynor at Matthew’s flat

(Image credit: Courtesy of Gaynor Prior)

The Fashion and Textile Museum exhibition is curated by Martin Green and NJ Stevenson. Green, who was a regular on the 1980s club circuit, is the co-founder of Duovision Arts, a Liverpool-based organisation which produces exhibitions by undervalued artists, photographers and designers engaged with the LGBT+ community. Stevenson, is a fashion curator, author and lecturer at London College of Fashion.

Together, they have also produced a book to accompany the show titled Outlaws Fashion Renegades of Leigh Bowery’s 1980s London, which delves further into the role that make-up and hair played in shaping London’s counterculture.

Mike Nichols and Matthew Hawkins

(Image credit: Courtesy of Joan Burey)

‘Make-up became another tool in the quest for reinvention and individuality. Clubbers practised at home until they reached professional levels of application and experimentation.’

NJ Stevenson

‘Charles Fox, the theatrical costumier in Covent Garden, stocked Kryolan make-up which produced Aquacolour – a staple of club looks,’ says Stevenson. ‘In the early 1980s, Charles Fox had a huge sale and the Blitz Kids snapped up period pieces which raised the bar of club dressing up. Leigh Bowery used Aquacolour for his extreme looks at Taboo; the drips look was Copydex glue mixed with pigment.’

‘Make-up became another tool in the quest for reinvention and individuality. Clubbers practised at home until they reached professional levels of application and experimentation,’ she continues. ‘Competition and rivalry meant nothing was too extreme.’ This would range from artist Matthew Glamorre painting his teeth with nail polish to the experimental work of Swedish make-up artist Jalle Bakke, whose diaries are on show in the new exhibition. Bakke, who died of AIDS in 1996 at the age of 35, brought the avant-garde aesthetic of Taboo to Michael Clark productions, covers of I-D and The Face and music videos for ABC and Neneh Cherry.

Make-up artist Jalle Bakke

(Image credit: Courtesy of Corrine Charton)

‘Do you want to be a 1930s starlet or do you want to be Victorian punk? Make-up is the vehicle in that. It’s so important when turning looks,’ says icon of New York nightlife, Susanne Bartsch. Born in Bern, Switzerland, Bartsch moved to London as a teenager during the late 1970s, becoming a key player on the Soho scene.

It’s midday in the Big Apple when we speak over a call and the 59-year-old Bartsch is planning her look for a party she’s hosting later that night. ‘I often plan the make-up first. I’ll do the make-up and then I’ll see what I have in my closet,’ she says, with a Siouxsie Sioux-inspired wig at the ready.

David Walls, Leigh Bowery and friends in London, 1983/4

(Image credit: © Michael Costiff)

Bartsch has lived in New York since the 1980s. On her return from London, she saw a gap in the market for the mischievous, maximalist spirit of the Blitz Kids. ‘People weren’t doing looks in New York. If you had a flower in your hair you were dressed up. It was very Calvin Klein, very minimal, very chic. People were well dressed but it wasn’t colourful and expressive,’ she says.

Through starting her weekly underground parties inspired by the energy of Taboo, the city’s own club kid movement was born, of which Amanda Lepore, Michael Alig and James St James were a part. ‘I think I brought that whole movement to New York, through what I experienced in London with Blitz and the New Romantics,’ says Bartsch.

‘I first met Leigh in his apartment. His face was painted blue and he had off-centred, abstract lips.’

Susanne Bartsch

Nicola Tyson

(Image credit: Courtesy of Joan Burey)

She also introduced New York to London’s most extravagant club kid of all, Bowery, who was by then a close friend of hers. She vividly remembers Bowery’s singular looks, which ranged from those signature drips of coloured Copydex running down his bald head like candle wax to absurdly spiked wigs and gimp masks with lightbulbs for ears.

‘I first met Leigh in his apartment. His face was painted blue and he had off-centred, abstract lips,’ she recalls. ‘We just clicked. I asked to buy some of his stuff and so he started making things for me. I took him to Japan, then I introduced him to New York. [His look] was very strong. His personality and charisma had a lot to do with it. But the look was very new to me, I hadn’t seen anything that was put together like he put it together.’

Leigh Bowery and friends at Taboo

(Image credit: Courtesy of Scarlett Cannon)

The important role that Taboo played in the time of Thatcher’s Britain cannot be overstated. LGBT+ people faced rampant homophobia and discrimination, the AIDS pandemic was sweeping the globe, and the introduction of the 1988 Section 28 law preventing councils and schools from ‘promoting the teaching of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship’ was on the horizon.

Spaces like Taboo provided a dark, dingy, but beloved queer utopia. Those who were unable to express their truest self during daylight hours could become whoever they wanted to be under the cover of nighttime. Through fashion, make-up and hair, wearers were able to experiment with different – and perhaps more accurate – representations of their inner beings, with a vital sense of playfulness.

Jeffrey Hinton, Lanah Pellay and Richard dancing at Taboo

(Image credit: Courtesy of Scarlett Cannon)

Though Bowery died in 1994, his and The Blitz Kids’ influence on culture has endured to this day. Make-up artist Val Garland has frequently referenced his overdrawn lips and fearsome face paint in runway shows for Alexander McQueen, Rick Owens and Gareth Pugh. Dame Pat McGrath – who as a twentysomething used to follow Bowery, Strange and Boy George down the King’s Road in awe – has dedicated make-up palettes from her namesake beauty line to the club kids of the 1980s and beyond.

‘It’s an art form; it’s embracing yourself and using your body as a canvas,’ says Bartsch, of the ritual of dressing up. ‘It’s a lot of work putting together a look, then executing it is like making a sculpture. It’s a way to show your talents and have fun. The bottom line is that it’s fun. You’re reinventing yourself and seeing how far you can go.’

Outlaws: Fashion Renegades of 80s London is open at the Fashion and Textile Museum from 4 October 2024 to 9 March 2025.

fashiontextilemuseum.org

Princess Julia and Scarlett Cannon

(Image credit: Courtesy of Scarlett Cannon)