We all know the saying “Less is more.” Over the past century, the aphorism has become a battle cry for architects and designers, defining a modernist aesthetic that champions the minimal and the refined over the busy and the ornamental as a path toward better living. But has our understanding of minimalism itself become a little too reductive? And does it even fit with our collective ethos here in 2024?

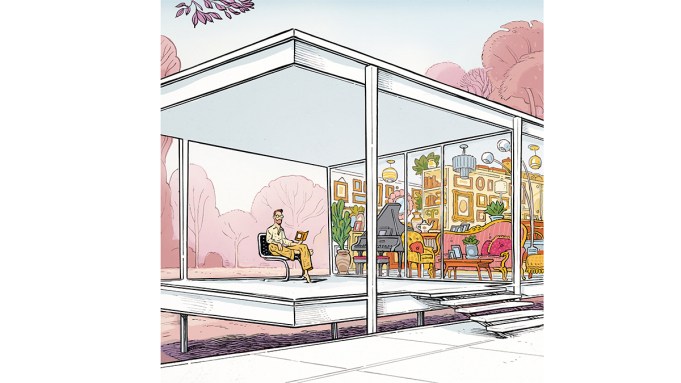

While the pithy phrase was popularized by the 20th-century German American architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, it doesn’t apply to the way many of his clients actually lived in his buildings. Photographs of Farnsworth House, his modernist glass-box icon, show a space arranged as Mies had envisaged it, with his streamlined furnishings and pared-back interiors.

In fact, the home was inhabited quite differently by the physician and poet who commissioned it and for whom it is named: Dr. Edith Farnsworth—a lover of music and travel—enlivened her weekend house with eclectic furnishings and mementos that, in sum, were anything but minimal.

What this example illustrates is that maximalism has always existed alongside minimalism. While history loves a linear progression from one clear idea to another, the reality is that culture is far more complex and multifaceted. The past century has been defined in many circles as an era of minimalism, peaking in recent years with the rise of declutter advocates such as Marie Kondo and Fumio Sasaki, but “More is more” has always been bubbling beneath the surface. Today, it just might be boiling over.

In 2019, Swedish sociologist Ylva Uggla analyzed the core ideas behind the growth of minimalism in contemporary Western culture. She found the minimalist lifestyle, with its celebration of downsizing, had been trending in countries such as Japan, the U.S., and Sweden over the previous decade. Although it often manifested itself in people’s physical environments, Uggla discovered it was driven by psychological factors.

“Minimalism,” she posited, “is primarily an individual approach to dealing with situations of discontent.” Examining the writings of famous pro-minimalist bloggers and authors, Uggla ascertained that while the forms of minimalism being advocated took various shapes, they shared a common core aim: to shift away from dissatisfaction and toward a more meaningful life. In short, decluttering our spaces and buying less “stuff” became a means, in a culture increasingly defined by consumption, to take back autonomy.

That consumerist culture now resides online and, rather than overwhelming us with endless options for products and experiences, digital algorithms increasingly feed back to us what we already like. Kyle Chayka, author of Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture, recently stated: “The problem with this ecosystem we’ve developed [where we are] surrounded by algorithmic recommendations is that it prevents us from being challenged and surprised. Everything is molded to our preferences that we’ve already expressed.”

The result? Ubiquity. And so, the very consumerist culture that ignited a yearning for a less-is-more aesthetic—one in which decluttering and disavowing excess stuff signaled freedom and independence—is now swinging in the opposite direction: In the spaces where we spend our lives, the more discerning among us are craving something outside the algorithmic formula.

“Today, maximalism is emerging as a refreshing departure from the mundane, repetitive, and predictable paths of minimalism,” says Amanda Jacobs, an interior designer based in Louisville, Ky. “Maximalism celebrates mistakes and encourages bold self-expression without being bound by rigid formulas. It leads to intriguing combinations that reflect one’s unique taste and personality, and it’s never monotonous, because no two individuals are the same.”

For Jacobs, the shift reflects a deep cultural longing for authentic personal expression—something the algorithms can’t feed us. In an age when we can push a button and have any number of home furnishings delivered to our doorstep, we seem to be coveting objects and designs that help us feel something deeper within ourselves.

“An interior with character and soul acts as a reflection of its inhabitant; it conveys their identity,” says Leah Harmatz, founder of San Francisco design studio Field Theory. And designers are responding to this need. Just as interiors filled with personal mementos and heirloom furnishings or walls lined with shelves of favorite books and artworks can inspire sentimental meaning for their owners, many designers today are gravitating to maximalist projects because they allow for more creative expression.

“I love working with people who know what they want and don’t care what their friends are going to say when they come over—I never like to do the same thing twice,” says Florida-based interior designer Elizabeth Ghia. The more individual people are with their interiors, she maintains, the more interesting they are.

And why shouldn’t our spaces, where we go to find respite and warmth, reflect back to us our idiosyncratic interests and desires? There’s no better place to display expressions of our individuality—not to mention memories—than our homes. Of course, it’s ultimately less important whether we appreciate minimalism or jump headfirst into maximalism. What matters most is that we consciously choose what rings true to us.

Lauren Gallow is a Seattle-based journalist—and an adviser at Pacific Northwest design platform Arcade—whose graduate studies in architectural history inform her writing today about design in all its forms.