After World War II, a network of conservative politicians, religious leaders, sympathetic journalists and like-minded organizations in the United States devised a plan.

This plan sought to turn back the clock on gains made over the previous decade by African Americans, women, workers and others, believing that “real” American values were rooted in the past. To criticize America, in the eyes of this newly established network, was to “chip away at our confidences” to allow a “special brand of tyranny” to “creep into America.” Members of this network considered criticism of their agenda subversive—evidence of “diabolical plots to wreck the American way of life.” Their mission was straightforward: generate fear of ideas that diverged from theirs, brand their critics as Communists, and call for purges of government, education, labor and media.

This plan sought to turn back the clock on gains made over the previous decade by African Americans, women, workers and others, believing that “real” American values were rooted in the past. To criticize America, in the eyes of this newly established network, was to “chip away at our confidences” to allow a “special brand of tyranny” to “creep into America.” Members of this network considered criticism of their agenda subversive—evidence of “diabolical plots to wreck the American way of life.” Their mission was straightforward: generate fear of ideas that diverged from theirs, brand their critics as Communists, and call for purges of government, education, labor and media.

Fear is a volatile weapon, especially in the wake of a traumatic global event like World War II, requiring careful management of the flow of information. Anti-communists, as they would come to be known, had been monitoring radicals and liberals (who they labeled “fellow travelers”) in media for years. After World War II, they stepped up attacks on those who supported New Deal programs, like Social Security, fair labor practices and consumer rights, and condemned critics of U.S. domestic or global policy. In 1946, liberal commentators at a leading Los Angeles radio station were fired and the American Legion began coordinating campaigns against those who had been listed as subversive in the pages of CounterAttack, a newsletter established to provide “facts to combat communism.”

Chairman of House Committee investigating Un-American activities, proofs & reads his statement replying to Pres. Roosevelt’s attack on the Committee, Oct. 26, 1938. Harris & Ewing, official White House photographers, Library of Congress.

Since firing people for their political beliefs evoked the fascism only recently defeated in Germany and Italy, anti-communists were careful to emphasize that their fight against “Stalin’s stooges” was legal. The American Legion led the way in encouraging both a “vigilant public opinion and a struggle against communism within the framework of law and order.” This is where the blacklist came in. The playbook looked like this: the American Business Consultants – publishers of CounterAttack, an anti-communist newsletter – identified so-called Communists and “fellow travelers” in the newsletter. They then visited networks, advertisers, sponsors and individuals to offer their services for a fee to “clear” those they had identified. Typically, clearance required blacklisted individuals to cooperate with the FBI or the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) by providing names of other subversives and publicly renouncing all progressive political affiliations. If individuals did not comply, the FBI and anti-communist organizations then pressured organizations and institutions to eliminate blacklisted personnel by coordinating letter writing campaigns threatening negative publicity and boycotts. In the case of media industries—especially vulnerable to smear campaigns—these threats gave networks and advertisers justification for firing employees because, they maintained, the public had demanded it.

The media blacklist is often said to have begun in 1947, when a group of motion picture professionals identified as Communists by political rivals were called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

These men—the Hollywood Ten—refused to answer questions about their political affiliations on the grounds that being forced to answer violated their First Amendment rights. The court disagreed and a year later, the Ten were convicted of contempt of Congress and sentenced to up to a year in prison. In June 1950, having exhausted their appeals, the Hollywood Ten went to prison.

Charged with contempt of Congress, nine Hollywood men give themselves up to U.S. Marshal in December 10, 1947. From right: Robert Adrian Scott, Edward Dmytryk, Samuel Ornitz, Lester Cole, Herbert Biberman, Albert Maltz, Alvah Bessie, John Howard Lawson and Ring Lardner Jr. UCLA Library Special Collections, A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, CC.

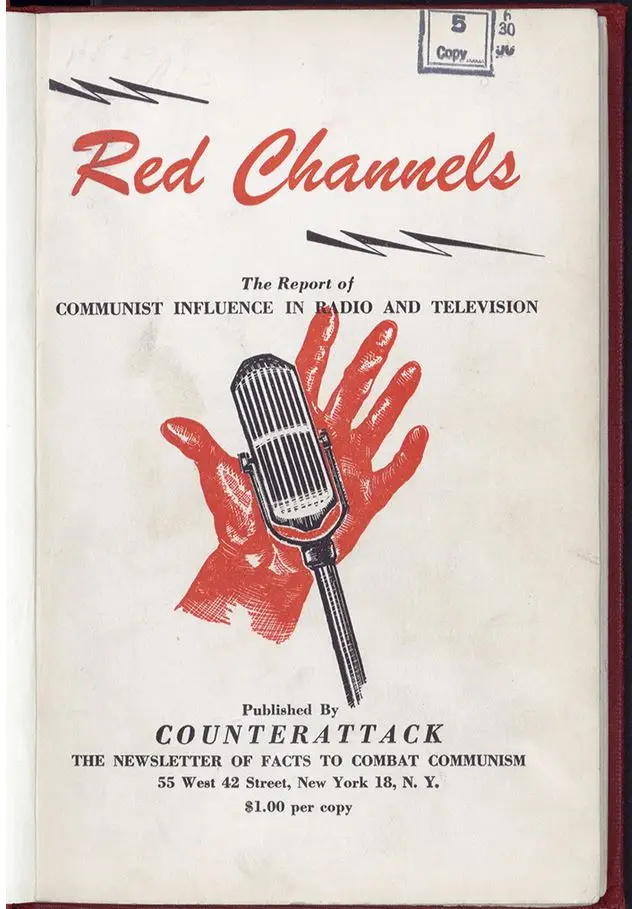

“Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television.” New York: Counterattack, 1950. Reproduction. General Collections, Library of Congress

That same month, days before the U.S. formally entered the Korean War, the three ex-FBI agents who owned the American Business Consultants published a slender volume that would soon become known as “the bible” of the broadcast blacklist. Titled “Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television,” the introduction was written by a former military intelligence officer turned aspiring radio writer turned FBI confidential informant.

“Red Channels” contained the names of 151 people working in media and related professions.

The book accused them of advancing Communist objectives “by indoctrinating the masses of people with Communist ideology and the pro-Soviet interpretation of current events.” Next to the names of the accused were lists of affiliations that “proved” they had been following the “Communist line of the moment.” Many on the list had supported efforts to address what anti-communists dismissively referred to as “racial discrimination,” like desegregating broadcasting, supporting anti-lynching legislation and criticizing police violence and death penalty sentences meted out to Black defendants by all-white juries. Anti-communists charged these critics with being dangerous and un-American.

This was not an attack on a political movement, so much as it was an offensive against political ideas, as the rhetoric of the anti-communist movement plainly showed. After stating that one news commentator had not been a member of the Communist Party, a report from a Los Angeles FBI agent added that the person “dwells at great length on subjects which go to make up the present Party line, namely racial discrimination, need for full employment legislation, the need for sharing the atomic bomb with Russia, withdrawal of troops from China, etc.”

![Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.) 1854-1972, August 28, 1950, Page A-8, Image 8 Image provided by Library of Congress, Washington, DC](https://static.beescdn.com/news.myworldfix.com/2025/02/20250301002519420.jpg?x-oss-process=image/auto-orient,1/quality,q_90/format,webp)

Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.) 1854-1972, August 28, 1950, Page A-8, Image 8 Image provided by Library of Congress, Washington, DC

The first high profile blacklisting case in broadcasting involved actress Jean Muir, hired to play the mother in sitcom “The Aldrich Family.” The American Business Consultants organized a letter-writing campaign alleging that Muir was a member of the Communist Party (General Foods, the network and sponsor, was said to have received fewer than a dozen messages). CBS promptly fired Muir. The station’s executives considered her to be “‘a controversial personality” whose presence “might adversely affect the sale of products advertised during the show.” Privately, FBI agents wrote that Muir had “been active in fighting racial discrimination.” An informant, agents said, had accused Muir of encouraging popular New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia (another target of anti-communist attacks) to organize a committee to investigate instances of discrimination.

Hazel Scott, 1936, Private Archive – Library of Congress

Made bold by Muir’s firing, anti-communists followed up with fresh attacks on African Americans listed in the pages of “Red Channels.” Hazel Scott’s groundbreaking new variety show—the first television show to feature an African American in a starring role—was cancelled just days after Scott read a statement condemning blacklisting before a panel of politicians committed to segregation and the belief in white supremacy.

Paul Robeson had made an impassioned plea for peace at a 1949 Paris conference that resulted in a backlash coordinated by government and media. In the wake of “Red Channels,” the U.S. government declared his passport invalid because his travels abroad were allegedly against the best interests of America.

Actor Canada Lee was also denied a passport, which would have allowed him to seek work in Europe after the blacklist made him unemployable in the U.S. Novelist and civil rights advocate Shirley Graham, author of novels chronicling African Americans’ contributions to history, had adapted her novel about poet Phillis Wheatley into a 1948 CBS teleplay. After being listed in “Red Channels,” Graham found herself unable to get contracts for her books.

Many listed in “Red Channels” refused to cooperate.

Actor Canada Lee was told that he could clear his name by identifying Paul Robeson as a communist. He refused. Writer Lillian Hellman told the House Un-American Activities Committee that she refused to name names and in so doing “bring bad trouble to people who, in my past association with them, were completely innocent of any talk or any action that was disloyal or subversive . . . . I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.”

Shirley Graham Du Bois, by Carl Van Vechten, 1946, Library of Congress.

In the end, blacklists succeeded because anti-communist individuals and organizations worked with the implicit support of the FBI. The Bureau had considerable evidence that the authors of “Red Channels” had stolen classified government files for use in their new business and were using illegal tactics (including wiretapping and rummaging through suspected subversives’ mail and trash). Anti-communists were also not afraid to threaten FBI retaliation to persuade blacklisted personnel to comply with their demands. For example, choreographer Jerome Robbins, already fearful that his homosexuality would be exposed, was told by the American Business Consultants that “it was to his definite advantage that he straighten himself out as soon as possible for if an Atom Bomb were to be dropped the FBI would no doubt pick up Robbins as the first of those rounded up.” Because the American Business Consultants was using information obtained from FBI files, the FBI also knew that much of what the business was presenting as fact in the pages of CounterAttack was not true. The Bureau took no action against their former agents.

By turning political beliefs into conditions for employability, the broadcast blacklist narrowed the range of political debate. Certain topics became indicators of subversive ideas that could get people fired. In spring 1950, CBS assured the FBI that the network was going to “clean out any people that would not be the right type of people there.” And clean it did. By December 1950, CBS had fired several members of its renowned documentary unit, including Mitchell Grayson (director of “New World a-Comin,” a radio program about issues facing African Americans) and Bill Robson (winner of a Peabody Award for his “Open Letter on Race Hatred”).

Prominent African American artists like Hazel Scott, Canada Lee, Shirley Graham, Fredi Washington and Paul Robeson disappeared from writers’ rooms screens and stages. These disappearances sent a clear message to the industry: conform to the anti-communist line or be subject to retaliation and loss of employment. A generation of liberal and radical actors, writers, directors, producers and filmmakers was silenced, forced out of the industry or made speechless by fear.

By equating dissent with un-Americanism, the blacklist made it dangerous to give voice to political alternatives within the powerful new medium of television. Claiming that media had been infiltrated by Communists and the all-encompassing category of fellow traveler, anti-communists infiltrated and intimidated media industries until they complied with their political demands. The ultimate success of the blacklist was to obscure the memory of the influential progressive movements and individuals of mid-20th century America, and with them, to obscure their hopes for a different, more just America.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer.