Directors of the college’s three schools share their stories

Kinh Vu is known for his animated classroom style, but nobody saw the directors dance party coming.

Vu popped on the BeeGees’ “Stayin’ Alive” so everyone could loosen up at the start of a recent session of Doing, Making & Knowing: The CFA Experience (CFA FA 100). The 150 or so first-year College of Fine Arts students stretched and shimmied, and for a moment or two, watched the directors of all three CFA schools—there is no other way to say this—getting down. As much as possible at 10 am, anyway.

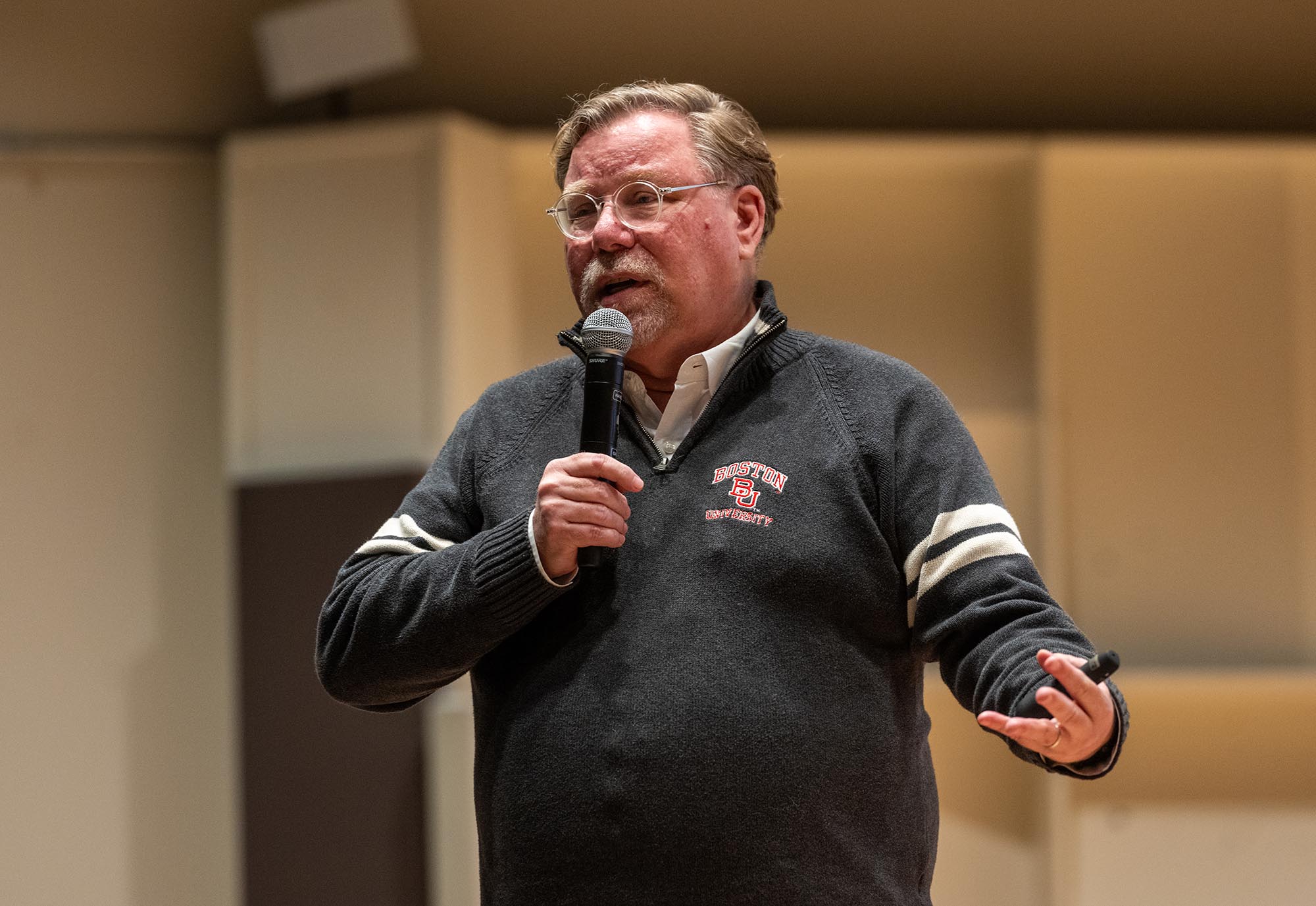

Guest speakers Gregory Melchor-Barz (School of Music), Dana Clancy (School of Visual Arts), and Susan Mickey (School of Theatre) were there to share their experiences as artists working in the world. “It is vital for students to hear directly from these educator/artist/administrators about why it’s so important to be courageous and caring creatives in the world today,” Vu, a CFA assistant professor of music, says.

The impromptu disco breakout “was a beautiful and fun way to kick off the class,” he says, because it gave the students a chance to see the three leaders just enjoying themselves as people.

Required of all CFA first-years, FA 100 is an unusual class: it’s not about how to make a particular kind of art, but rather, more broadly, how to make an artistic life. The course also fulfills a single unit in the BU Hub area Philosophical Inquiry and Life’s Meaning. Other speakers this semester have included Carrie Landa, executive director of Student Wellbeing, and Andre de Quadros, a CFA professor of music. Assignments can range from a “walkabout” reimagining various campus locations as public arts spaces to a wide-open final project demonstrating students’ development as artists.

The syllabus is extensive, but some of the lessons are intangible, which also proved true with the three directors.

Lately the class has been working with questions drawn from Elizabeth Gilbert’s book Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear (Riverhead Books, 2015): What have I been called to do? How am I getting in my own way? How can I best live out my destiny?

Melchor-Barz, a professor of ethnomusicology, offered a story about how he eventually learned to get out of his own way.

He told the class he came out of conservatory in the 1970s and being “so interested in knowing how to know music, to know the arts, that I never took the time to focus on how to be the arts, how to be music.”

Having learned Swahili, he said, he went to do research in Tanzania, where a great drummer and teacher said to him, “‘Gregory, you keep saying muziki, what is that term?’ So I pulled out my Oxford Swahili/English dictionary, and looked it up. ‘Muziki means music.’”

The drummer noted that the dictionary was published in England, land of the colonizers, not Africa. “And he looked down at the village, and pointed out this little Anglican church. There was some choral singing coming out of the church, and he said, ‘That’s muziki, that’s music.’”

Confused, Melchor-Barz picked up his ngoma drum and began to play. “And I said, ‘Teacher, what is it that I am doing now? Is that music?’ And he said, ‘That’s not music, that’s ngoma.’ And he started dancing, and I said, ‘What is that?’ And he said, ‘That’s ngoma.’ And he started singing. ‘What is that?’ ‘Ngoma.’”

Melchor-Barz made a ka-boom sound. “My head explodes. Because there is something about being musical in East Africa that doesn’t involve western harmonies, western music. There’s a way of being musical, from an African perspective, that is different from anything I was ever taught in my conservatory training in New York. I had to get rid of my ways of understanding how I was in the world musically, in order to understand how somebody else was in the world musically.”

I had to get rid of my ways of understanding how I was in the world musically, in order to understand how somebody else was in the world musically.

Next, Vu showed slides of work created during the pandemic by Clancy, a painter, who in a very meta choice used pages of the Sunday New York Times for canvases that she covered with portraits of artist friends she gathered with regularly on Zoom.

“This is a project that evolved very organically. I had the New York Times under my computer because I didn’t want to get paint all over my desk while I was having Zooms,” Clancy, an associate professor of art, painting, said. “The news is in the foreground. How do I bring this large abstract world of very pressing political issues, very pressing health issues, into my studio? What do I do with it? Being a painter means asking questions with painting.”

The pictures are also covered with text, sound bites from Clancy’s conversations, such as “You learn by doing.” Asked for his interpretation, one student misread it as, “You learn by dying,” which, given the context—George Floyd’s murder and COVID—was met with nervous laughter.

Mickey, who is also a professor of costume design and has a long record of success on stage and screen, had the most crowd-pleasing visuals, a slide show of her costumes for a variety of plays and operas around the world, variously outrageous, funny, and grim.

“At parties and dinners, I get asked, ‘What do you do?’ And they always say, ‘Oh, that seems so fun!’” Mickey said. “I used to get a little miffed. It sounded a little condescending. But what I say now is, ‘Yes it is! I have more fun than anyone.’”

That doesn’t make it any less serious, however.

“I just did an opera in Sweden this summer,” Mickey said (read about it here). “Normally the costume shop is not where the singers are working. But in this space the opera singers’ studios and dressing rooms were on the same floor, and I could hear them rehearsing and tuning their instrument of their voice, every day, all day long. It was so stunning to me the amount of work.

“As you look around you these days, there’s a lot going on that is really difficult. You want to ask yourself, what does my designing a bunch of fluffy dresses have to do with how messed-up the world is?” she told the class. “I had a student, an actor, a couple of years ago, and amid all of the heartbreaking stuff that was going on, he was in a children’s play, singing a silly song, and he just says, ‘Why am I doing this? It feels like I should be doing something more.’

“I told him, if you can make somebody laugh today, it may change everything for them. It could mean the world. I truly believe that art and education will change the world, will make this a better place. The things you create elevate the conversation. It makes our souls and minds better. It may be fun and fluffy sometimes, but also, it is the world.”