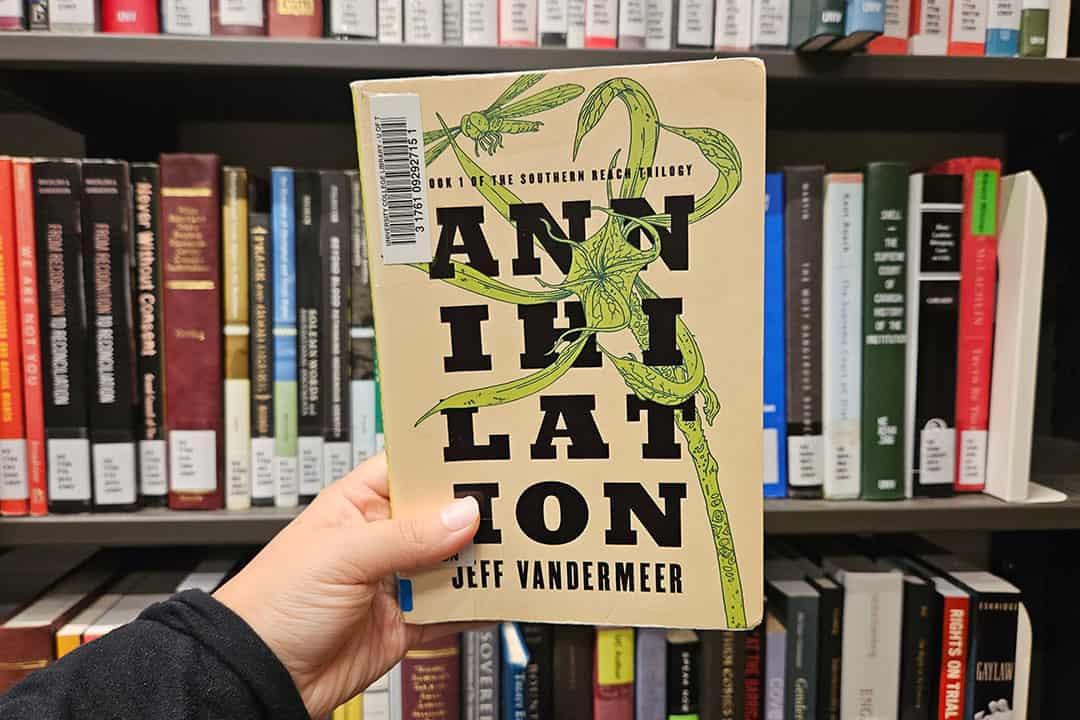

Annihilation takes the reader on a journey into the unknown horrors of nature. Margad Sukhbaatar/THE VARSITY

A review of Jeff VanderMeer’s 2014 novel Annihilation

The word “annihilation” rang fresh as pricked blood to me as I picked the book off my bookshelf. In approximately a quarter of a breath, Jeff VanderMeer had conjured in my mind a million racing images of existence and obliteration — of what, I didn’t know. Maybe nature, maybe humanity, maybe the world.

The story begins with a biologist. You never learn her name, just that she is on an expedition to an uninhabited region in the United States called ‘Area X.’ Her journey is funded and commanded by a mysterious government organization: the ‘Southern Reach.’ This alone could have compelled me to read it, but when I learned that Area X was based on the author’s 14-mile hikes through St. Marks Wildlife Refuge in North Florida, I was sold. According to VanderMeer, “It’s a place where you need to live in the moment, and yet can also, by doing so, be transported deep into memory and catharsis.”

The origins of Area X

The biologist is travelling with three other women — a psychologist, an anthropologist, and a surveyor — and old technology. They, too, are nameless, cautioned to leave behind even the most immaterial artifacts from their personal life. Their purpose in Area X is to explore, or so they think.

Make no mistake; this is not your average ‘human versus nature’ story. We follow the biologist as she uncovers the mysteries of the land she is on before it swallows her whole. Her fear of the land is always mixed in with awe, scientific fervour, and VanderMeer’s vivid descriptions of nature. Area X is not normal, but it is not supernatural either. VanderMeer’s construction of it is imbued with a deep respect for even the most terrifying natural landscapes.

The biologist is interested in transitional ecosystems, and as the story develops, you understand why Area X consumes her mind. It is an ecosystem constantly in transition, with reedy marshes, rivers, forests, and coasts all within a few miles.

Early in the story, the expedition group discovers a tower with writing on its walls. It’s human writing, legible for the entire group to read. However, what piques the biologist’s interest isn’t the contents of the words themselves but the ecosystem they beget. The words are made of fungi-like creatures shaped like tiny hands — a miniature ecosystem within an ecosystem.

Each creepy turn of the novel signals to the reader that the ecosystem is alive, not just in individual organisms but as a whole. This novel is about the biologist’s survival but not always in the ways that one would expect.

The edge of life

One of the things that entranced me the most about Annihilation was the biologist’s obsession with finding beauty in the smallest, most neglected, and changeable ecosystems. As someone who pauses to identify tree saplings between the pavement cracks, I resonated with this. At one point, the biologist describes how she observed a tide pool at night, where she saw a rare starfish: “The longer I stared at it, the less comprehensible the creature became. The more it became something alien to me, and the more I had a sense that I knew nothing at all — about nature, about ecosystems.”

This incomprehensibility, however, only drives her to discover more. She constantly dissects the relationships between these foreign organisms that coexist together, understanding that elements of ecosystems are interactive rather than isolated pieces.

I couldn’t help but think about the study of ecosystem processes through the frame of their biogeochemical cycles. In most ecosystems, these cycles are far less baffling than the ecology of Area X, and studying them allows you to see the ecosystem as a whole. In doing this, it’s much easier to solve real-life ecological puzzles about how the most intricate parts of a biome interact. A British Columbia’s Ministry of Forests pamphlet says it best: “A degraded stream channel is not a problem in and of itself, but rather a symptom of a degraded water cycle.” In other words, small-scale changes in an ecosystem can be traced to its larger systems.

Annihilation is a tale about the way that ecosystems change, and the ways that humans have — or have not — been able to change nature. It’s about an ecosystem as one being, as a whole, split into infinite parts. It’s a love letter to North Florida landscapes, to ecology, and to nature. It’s a novel that changed my view of nature forever.