It’s taken more than four billion years for intelligent life to emerge by natural selection on Earth, but there are billions more years ahead in our planet’s lifetime. Over that time, intelligence could develop in entirely new directions.

Comment & Analysis

Lord Martin Rees is the UK’s Astronomer Royal, and is based at the University of Cambridge. His most recent books are If Science is to Save Us, and The End of Astronauts, co-authored with Donald Goldsmith.

We human beings may be near the end of Darwinian evolution – no longer required to become the fittest to survive – but technological evolution of artificially intelligent minds is only just beginning. It may be only one or two more centuries before humans are overtaken or transcended by inorganic intelligence. If this happens, our species would have been just a brief interlude in Earth’s history before the machines take over.

That raises a profound question about the wider cosmos: are aliens more likely to be flesh and blood like us, or something more artificial? And if they are more like machines, what would they be like and how might we detect them?

Not like us

Many assume that human beings are the peak of intelligence, but it’s possible that our species may represent a stage on the path towards minds that are more artificial. This could explain why the cosmos seems so empty of life like us. If an evolutionary transition to non-organic intelligence is inevitable across the Universe, our telescopes would be most unlikely to catch human-like intelligence in the sliver of time when it was still embodied in that form. It is perhaps more likely that the aliens would be the remote electronic progeny of other organic creatures that existed long ago.

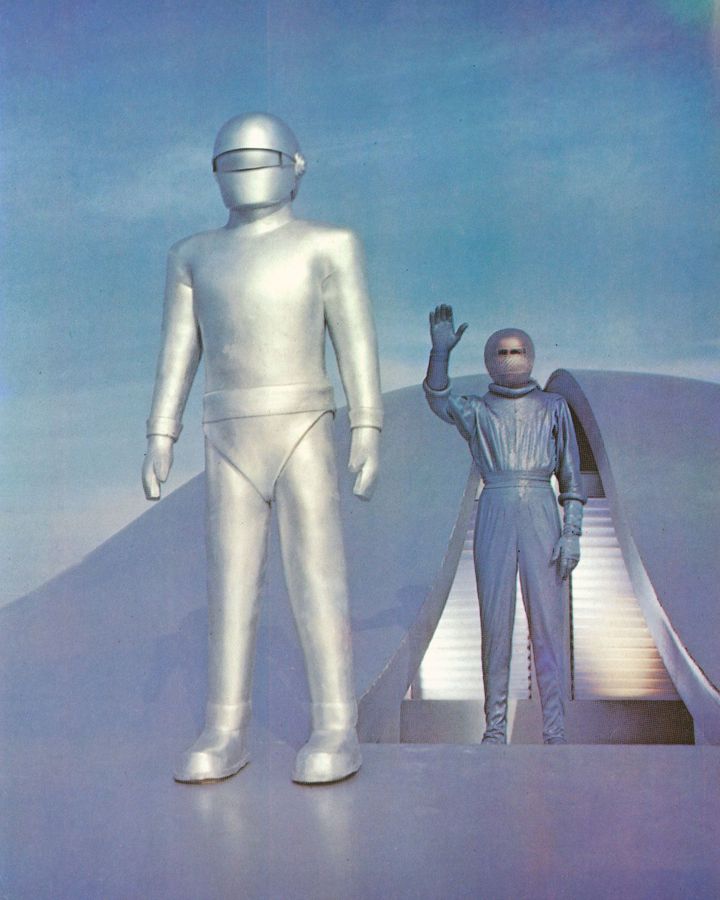

In the classic movie The Day The Earth Stood Still, one of the aliens is a robot – but still humanoid (Credit: Getty Images)

The prospect of inorganic alien intelligence raises some striking possibilities. If these beings are out there, they would act and think totally differently to us. They may not want to be detected. Indeed, their intentions may be impossible to fathom. To quote Charles Darwin, “A dog might as well speculate on the mind of [Isaac] Newton.” However, we might deduce a few things.

For one, non-organic intelligence may have no use for an atmosphere, or the planet on which they originated. Interstellar voyages – or even intergalactic voyages – would hold no terrors for near-immortals.

Indeed, they may prefer to live in zero-gravity, because there you can make very large, very lightweight objects. If you wanted to build a huge, elaborate gossamer-thin structure to harvest energy, for example, it’s easier in space than on a planet.

It’s also not obvious that they would need to live in orbit around a star. Perhaps they’d have new ways of getting energy that we just can’t envisage yet. If they have silicon-based brains, they might realise that the energy needed for processing “bits” is less at low temperatures, so they would expend less energy in colder regions away from planetary systems. They might even choose to hibernate for billions of years until the cosmic microwave background – the leftover radiation from the Big Bang – is further cooled by the continuing expansion of the Universe.

We look to the galaxies for life, but could AI aliens live in the cold inbetween? (Credit: STScI/Nasa)

They may not have the same base desires as us. We have evolved through Darwinian pressures to be an expansionist species. Selection has favoured intelligence but also aggression. But if Darwinian pressures do not apply to these artificial entities, there’s no reason why they should be aggressive. They may just want to think deep thoughts.

The fact we haven’t seen any, and haven’t been invaded by them, doesn’t mean there’s nothing out there. They may simply be more contemplative. We can’t assess whether the “great silence” of the cosmos signifies their absence, or simply their preference.

We also can’t assume that they’d even be a “civilisation”. On Earth, this term connotes a society of individuals: in contrast, ET might be a single integrated intelligence.

Pessimistically, they could be what philosophers call “zombies”. It’s unknown whether consciousness is special to the wet, organic brains of humans, apes and dogs. Might it be that electronic intelligences, even if their intellects seem superhuman, lack self-awareness or inner life? If so, they would be alive, but unable to contemplate themselves, or the beauty, wonder and mystery of the Universe. A rather bleak prospect.

Alternatively, their more advanced intelligence could well allow them to understand crucial aspects of reality that we cannot, just as a monkey can’t understand quantum theory. There could be complexities to the Universe that neither our intellect nor our senses can grasp, but electronic brains may have a quite different perception.

Implications for searching

If alien intelligence is more likely to be non-organic, what would this mean for the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (Seti)?

In a decade or two, there’s a realistic prospect that we’ll have the capability to detect biosignatures on other planets – atmospheric chemistry or vegetation, for example. But to detect artificial life, we would need to look for “technosignatures”, such as electromagnetic transmissions. (Read more about how astronomers are looking for life on other worlds.)

The Green Bank telescope in West Virginia has monitored a bizarre cigar-shaped object called Oumuamua (Credit: Getty Images)

The focus of Seti has been on the radio part of the spectrum. But of course, in our state of ignorance about what might be out there, we should explore all wavebands: the optical and X-ray band. Even if messages were being transmitted, we may not recognise them as artificial because we may not know how to decode them. Consider the difficulty a veteran radio engineer familiar only with the amplitude-modulation of the 20th Century might have decoding modern wireless communication.

Finding non-organic intelligence also means being alert to evidence of non-natural phenomena or activity – even within our own Solar System. It was right that the Green Bank telescope stayed pointed at Oumuamua, the anomalous object that passed through our neighbourhood recently and is believed to have originated from outside our Solar System. It’s also worth keeping an eye open for especially shiny or oddly-shaped objects lurking among the asteroids. We may also need to seek evidence for non-natural construction projects, such as a “Dyson Sphere”, a giant, hypothetical energy-harvesting structure built around a star.

In sum, astronomers like me should expect surprises. We ought to be open-minded and make sure that we wouldn’t miss anything odd.

You may also like:

- Could we find alien life via its pollution?

- The weird aliens of early science fiction

- Seven things science has revealed about aliens so far

Scientists still don’t know whether the origin of life is rare, and only happened here on Earth. But if that’s not the case, and if life gets started elsewhere, then intelligence could evolve in all sorts of ways. There are planetary systems out there that are at least a billion years older than our own, so it’s possible that intelligence has already developed into something nonorganic.

Perhaps whatever is out there doesn’t evolve by Darwinian selection: it would be what I call “secular intelligent design” that’s a bit like machines designing better machines. And while it may not be broadcasting its existence to us, it could be found throughout the Universe.

*This article is as told to Richard Fisher. Lord Martin Rees is the UK’s Astronomer Royal, and is based at the University of Cambridge. His most recent books are If Science is to Save Us, and The End of Astronauts, co-authored with Donald Goldsmith.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.