In new collections by Yiyun Li, Claire Keegan, Alexandra Chang and Lore Segal, interpersonal bonds are created and destroyed.

The short-story writer “can’t create compassion with compassion, or emotion with emotion, or thought with thought,” Flannery O’Connor wrote. “When you can state the theme of a story, when you can separate it from the story itself, then you can be sure the story is not a very good one.” By this metric, Claire Keegan’s SO LATE IN THE DAY: Stories of Women and Men (Grove, 119 pp., $20), a collection of one novella and two short stories all exploring misogyny through the eyes of women who react to it and men who blister with it, is nothing short of a masterpiece. Through narratives of a canceled wedding, a writer’s interrupted residency and a woman’s dangerous infidelity with a stranger, Keegan’s delicate hand directs the reader away from obvious moralizing to the banality of bigotry.

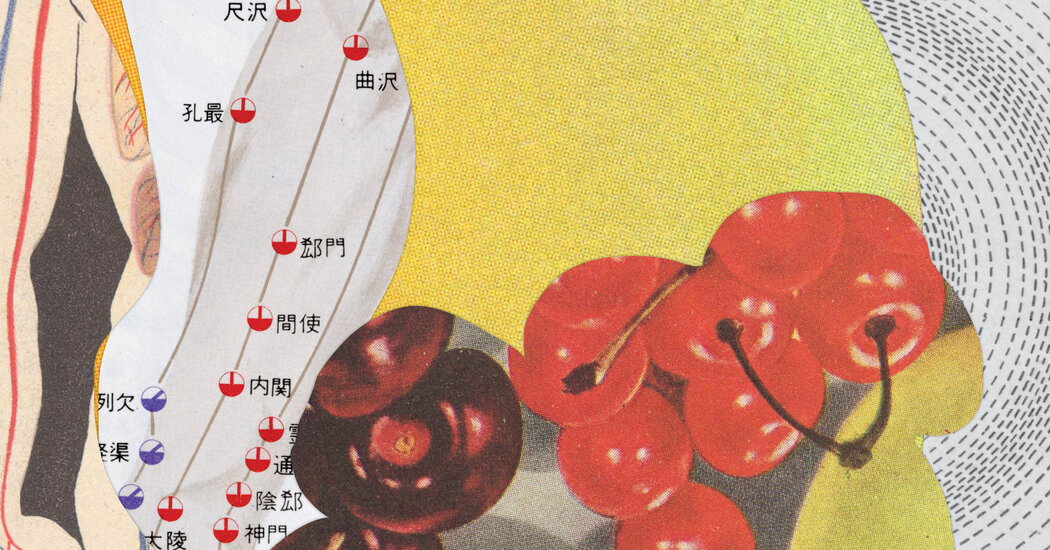

In the title novella, the Irish author of “Small Things Like These” and “Foster” portrays the jilted Cathal just after his fiancée, Sabine, has left him. He tallies up their relationship as a ledger of costs and burdens: cherries he begrudgingly paid for when she forgot her wallet, the catalog of possessions she moved into his home “as though the house now belonged to her also.” By withholding Sabine’s accusation of his chauvinism until the second half, Keegan circumscribes the reader within the small obsessions of Cathal’s bitterness, pitilessly rendering the most insidious biases held by those who cannot see themselves.

As if to imply that such hatred and repression defy figurative comparison, the closest the fiction comes to poetic metaphor is in Cathal’s avoidance of small talk with a stranger on a bus, his clipped replies “threading the speech into a corner, where it might go no further.”

By contrast, TOMB SWEEPING: Stories (Ecco, 239 pp., paperback, $18.99), Alexandra Chang’s follow-up to her debut novel, “Days of Distraction,” evinces little in the way of memorable character, emotion or conflict. Though the stories’ thematic concerns with the slipperiness of class in America, particularly as experienced by immigrant communities, are necessary and compelling — characters painfully move up and down the rungs of housing security, education, employment and documentation — the collection mostly fails to convincingly situate these themes within the emotional particulars of each protagonist’s life. Feelings are baldly stated, rather than tendered through illustrative action: “She loved her mother so much it scared her”; “I haven’t felt so deeply for a friend since.”

In a book about the bonds between individuals who are trying to balance their own survival with the debts they owe to one another, an excess of dialogue is to be expected; but Chang’s relies too heavily on wooden exclamations like “geez,” “hmmm,” “yay!” and “duh,” dulling opportunities for insight.

Though Chang occasionally follows a formal curiosity to interesting effect — “Li Fan” charts a narrative of homelessness backward, questioning assumptions about exactly whom misfortune can strike — conclusions can read as faint and anodyne. At the end of “Klara,” the narrator thinks she feels her phone buzz with a text from her titular erstwhile friend, only to realize the vibration was a “phantom feeling.”

Slight dialogue belies gravity beneath in Lore Segal’s mysterious, mesmerizing collection LADIES’ LUNCH: And Other Stories (Melville House, 131 pp., paperback, $18.99), whose linked stories mostly follow a group of friends in their 80s and 90s living in New York City. A less careful reader may be charmed by these old women — struggling to recall certain facts, stowing their canes on their way to find martinis at a shiva — but Segal deftly undercuts society’s impulse to infantilize, even dehumanize, the elderly.

Her often hilarious characters display a depth of understanding that goes beyond the pedantry of forgotten details. “I will never understand why something made to look three-dimensional or virtual excites us more than the real thing in front of our noses,” Lotte says. “Mimesis,” her friend Farah replies. “Is it Aristotle or is it me who said we like a likeness, in which, I guess, we search for ourselves?”

If little happens in “Ladies’ Lunch,” the women’s sometimes schmaltzy conversations about their pasts and other people give way to rewarding portraits of who they are alone. The gradually diluting bond between Lotte and her oldest friend Bessie forms the shattering emotional center of the book; what seems in some stories like an innocuous distance between them reveals itself in others as an icy estrangement. In a letter to Bessie, Lotte describes her distaste for her friend’s wealthy, xenophobic husband, comparing his fenced lawn to “a toy garden kept inside the box it came in.”

Segal is a great manipulator of stereotypes, insisting that aging is less like a blithely layered painting than a gallery of conflicting portraits, often excruciating to entertain in the same mind.

Yiyun Li’s WEDNESDAY’S CHILD: Stories (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 241 pp., $27) is another triumphant, if more oblique, excavation of aging. In the simultaneously barbed and tender “Such Common Life,” the narrator swims easily between the minds of a middle-aged practitioner of Eastern medicine and an 88-year-old biologist who is skeptical of the former’s expertise. A skilled impressionist, Li juxtaposes sensuous images — an older woman ice-skating with an attendant’s hands on either side of her, “his role that of the sepals to her blossom” — with aphoristic daggers: “One’s way of living determines one’s way of dying.” The tight scope of the stories keeps sentimentality at the fence, and the real lives of the characters in quarrelsome proximity.

Though a virtuoso in more traditional, omniscient third-person narration, Li is at her finest in the modern, first-person register of the final story, “All Will Be Well,” told from the distance of decades and in the wake of losing a child. The narrator, a professor and mother raised in Beijing, remembers having long ago found herself “addicted to a salon” in California where she pretended not to understand the Cantonese spoken by its staff, telling them she was adopted by Dutch parents and raised mostly in the United States. The narrator never explains her reason for lying, or why she grew resentful as she listened to the salon owner’s stories of love left behind in her native Vietnam. This fascinating discontinuity between inner and outer lives reminds the reader that the best short fiction, even when it comments on the world at large, operates most powerfully on the level of the individual characters — complicating their visions of themselves and clarifying our understanding of the behavior that great pain makes possible.