Abstract

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a public health emergency of international concern on 30 January 2020 and then a pandemic on 11 March 2020. In early 2020, a group of UK scientists volunteered to provide the public with up-to-date and transparent scientific information. The group formed the Independent Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Independent SAGE) and provided live weekly briefings to the public via YouTube. In this Perspective, we describe how and why this group came together and the challenges it faced. We reflect on 4 years of scientific information broadcasting and discuss the guiding principles followed by Independent SAGE, which may be broadly transferable for strengthening the scientist–public dialogue during public health emergencies in future settings. We discuss the provision of clarity and transparency, engagement with the science–policy interface, the practice of interdisciplinarity, the centrality of addressing inequity, the need for dialogue and partnership with the public, the importance of support for advocacy groups, the diversification of communication channels and modalities, the adoption of regular and organized internal communications, the resourcing and support of the group’s communications and the active opposition of misinformation and disinformation campaigns. We reflect on what we might do differently next time and propose research aimed at building the evidence base for optimizing informal scientific advisory groups in crisis situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

COVID-19 and science advice on the ‘Grand Stage’: the metadata and linguistic choices in a scientific advisory groups’ meeting minutes

The Dutch see Red: (in)formal science advisory bodies during the COVID-19 pandemic

Science communication as a preventative tool in the COVID19 pandemic

Introduction

In early 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in the United Kingdom, an interdisciplinary group of scientists came together to engage with the public both directly (using social media1) and indirectly (through the mainstream media). We called ourselves Independent Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Independent SAGE, not to be confused with SAGE, the UK Government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies). The Twitter (now X) feeds of these scientists quickly became points of reference for both lay people and scientists who sought to understand the layers of complexity across numerous fields including virology, epidemiology, public health, psychology, communications, mathematical modeling and immunology, and examine how this complex intersection of multiple knowledge sources was being used to inform governmental policies and guidelines. As the haunting images from across the world revealed the extent and immediacy of the danger that pandemics pose in a globalized world, the task for Independent SAGE public communication efforts was clear: we sought to provide clarity and transparency in a fast-unfolding situation of unprecedented magnitude in the modern era. From the earliest weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was evident that the appetite for direct, timely, open and honest communication was huge as the public and scientists flocked to social media in search of information and advice.

Now that the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic has come to an end, we discuss our experience on Independent SAGE in three sections covering the group’s inception, its development as an example of science–public dialogue and how it came to a natural close. We consider how the learnings from Independent SAGE might serve as guiding principles for other, similar, groups in future public health emergencies. We also reflect on the limitations of our approach and what we might do differently next time. Finally, we identify some evidence gaps that could be filled by research on science communication.

Context and origins

By late January 2020, the severity and scale of the novel coronavirus outbreak in China was evident. In the high-stakes, low-certainty context of a fast-unfolding global public health crisis2, policymakers worldwide had the unenviable task of weighing competing options with stark life-and-death implications—and deciding how and how quickly to act as more evidence emerged3. In those early weeks, openness around UK policy decisions was scarce4. There was much debate (some of it acrimonious) about how the UK government should respond. Should borders close? Should mass testing be introduced, and if so, how? Should masks be worn, and if so, by whom and in what circumstances? If the health service became overwhelmed, who should be prioritized for treatment? Should existing research infrastructure and personnel be redirected to address shortcomings in diagnostic services?

In the United Kingdom, the maxim ‘scientists advise, ministers decide’5 was much repeated but obscured two problems. First, the attempt to draw a firm distinction between science and policy ignores that the implementation of research findings is itself a scientific issue, whether it be discussed through the lens of implementation science6—the social science of research utilization by policymakers7,8—or as policy choices in the context of political economy9. Second, it begs the question of what (and whose) science was being used to advise the government.

Government policy drew most directly on input from SAGE, the official UK Government Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies. The membership of SAGE, along with subgroups on modeling, behavioral science and emerging respiratory viruses, was decided by the government’s Chief Scientific Advisor, working alongside the Chief Medical Officer.

Membership and deliberations of SAGE and its subgroups were initially not public, until the UK government began to disclose—from May 2020— their membership, minutes and reports4,10. This change in approach followed a series of ‘secrecy rows’ over the public disclosure of financial and other interests held by members of SAGE. Until then, no-one outside government and SAGE itself had any direct knowledge of either who offered advice to Government (and, consequently, which areas of science were underrepresented or excluded from the advisory process) or of what that advice involved (and, hence, whether the government really was ‘following the science’, as was being claimed11). Onlookers simply could not tell whether lessons from previous UK pandemics and pandemic exercises12,13,14, or from the experience of other countries15, had been learnt, remembered or actioned.

SAGE is a subgroup of Cabinet Office Briefing Rooms (COBRA), a cabinet office committee for national emergencies that sits in the national security secretariat, where confidentiality is expected. Such constraints notwithstanding, the prevailing lack of information about the scientific basis of government COVID-19 decision-making in early 2020, and a perceived lack of candor over uncertainty16, was troubling to those outside the corridors of power.

Transparency is a critical antecedent of trust17, and trust (in both scientists and government) is a powerful determinant of adherence to public health measures18. While overall public trust in the government in the early months of 2020 was high, it was lower in more highly educated people and fell significantly, especially in England, over the next few months19,20,21,22. Also, in the 2 years leading to the exit from the European Union (on 1 January 2020), public opinion on policymaking in the United Kingdom had been highly polarized. The pandemic, however, posed a threat where unity of intent across borders was needed and where perceptions of party politics was detrimental. At the same time, there was an overwhelming amount of scientific research being produced and a surfeit of scientific information circulating on social media, much of it in the form of scientific preprints and hastily prepared journal articles of varying quality, which were often discussed by the public with insufficient context23. It became clear that additional efforts were needed to help the public contextualize, understand and navigate the scientific evidence relevant to policy responses to the pandemic.

In April 2020, Pulitzer-nominated journalist Carole Cadwalladr had the idea of convening an independent group of scientists to assess the United Kingdom’s pandemic approach and to conduct a public discussion on options for moving out of lockdown. Cadwalladr had recently founded ‘The Citizens’, a not-for-profit journalism organization focused on democracy, data rights and addressing disinformation. Cadwalladr invited Sir David King (UK Government Chief Scientific Adviser, 2000–2007) to chair the group and asked Professor Anthony Costello (a global public health expert who had previously worked with the World Health Organization (WHO)) to suggest other potential members.

By May 2020, the inaugural group of UK scientists had been convened. They were drawn from a purposefully wide range of disciplines including public health, epidemiology, mathematics, immunology, virology, evolutionary biology, clinical medicine, primary health care, behavioral and social sciences and public engagement with science. An expert in race equality was also invited into the group. The group chose the title ‘Independent SAGE’, to communicate its aim to serve as an advisory group, but also to signify autonomy from the government and other potential sources of political interference

From its inception, Independent SAGE deemed that as much evidence as possible should be made publicly accessible and communicated clearly, allowing this to be examined collectively to inform public debate. Yet more than this, there was an urgent need to address critical questions about public health measures with the public. This meant establishing a two-way dialogue, answering questions, respecting public doubts and acknowledging uncertainties. This was an evidence-based approach in itself, given that health interventions are known to be more effective when there is mutual trust19 and cooperation between scientists and the public24.

The science–policy ecosystem in the United Kingdom

Official SAGE and Independent SAGE were by no means the only actors in what might be called the ‘science–policy ecosystem’ in the early phase of the pandemic. Other official actors included government advisory groups such as the Joint Committee on Vaccines and Immunisation (https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/joint-committee-on-vaccination-and-immunisation), New and Emergency Virus Threats Advisory Group (https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/new-and-emerging-respiratory-virus-threats-advisory-group), Public Health England (which had a public facing dashboard and gave regular briefings; it was replaced in 2022 with another body) and the Office of National Statistics (which ran a regular infection survey and produced weekly statistics on COVID cases). Other unofficial actors included fact-checking services (e.g., Full Fact (https://fullfact.org) and the #CoronaVirusFacts alliance (https://www.poynter.org/coronavirusfactsalliance/)), public-facing platforms set up by scientists to broadcast their own emerging research findings (e.g., the large REACT-1 study of changing COVID prevalence across the United Kingdom), and those established by research bodies (e.g., UK Research and Innovation’s ‘coronavirus explained’ website) and academic societies (e.g., the Royal Society’s Data Evaluation and Learning for Viral Epidemics and Rapid Assistance in Modelling the Pandemic initiatives, which also involved interdisciplinary groups of scientists who sought to produce data-driven advice and recommendations outside the official government space), initiatives led by mainstream media (e.g., the popular BBC radio program ‘More or Less’, which pivoted to explaining and fact-checking COVID-19 statistics during the pandemic) and the independent Science Media Centre, which showcased key research findings and collated expert commentaries on them in a public-facing website. Some individual scientists established citizen science initiatives, which recruited large numbers of participants (e.g., Professor Tim Spector repurposed the ‘Zoe app’ that had been developed for a previous research study and recruited over 4 million people in United Kingdom to record their symptoms (or lack of them) and test results, and also used the app for communicating advice and information).

In this complex ecosystem, the unique aspects of Independent SAGE were threefold. First, our live interactions with the public were frequent (weekly), intensive (60 min), driven by topics and issues proposed by the public and systematically recorded and archived. Second, and mainly because of this frequent and intense interaction with the public, we developed a particular focus on inequalities and vulnerable groups, including the socio-economically disadvantaged, minority ethnic groups and the clinically extremely vulnerable. These were the groups who most often sought further clarifications of facts and regulations. Third, as explained further below, we were responsive in our liaison with unions, advocates and campaign groups, striving to support them in pursuing their goals.

The Independent SAGE approach

The first official meeting of Independent SAGE was held on 4 May 2020, as a 2 h broadcast live-streamed on Twitter and YouTube, where the scientists discussed the UK response to date and options for the future25. Key themes were learning from abroad, contact tracing, addressing the pandemic’s unequal impact and (re)building resilience in the health system. It drew an audience of several thousand. After the meeting, the members produced a report of broad public health and policy recommendations. This initial meeting showed that there was high demand for public-facing, interdisciplinary science and the group held several live briefings over the following weeks on specific topics (e.g., education26 and contact tracing27) where people were invited to ask questions directly to the group.

When (from 23 June 2020) the UK government ended its daily public briefings, Independent SAGE committed to a weekly 1 h briefing live-streamed every Friday lunchtime, which soon evolved into a structured format:

-

The numbers: a presentation of the latest data and trends in the United Kingdom and globally

-

Topic of the week: a specialist segment presenting a new Independent SAGE report or covering a theme in detail, featuring expert guests

-

Live questions from the audience, submitted by a very broad range of people including members of the public with either a personal issue (e.g., concerns about vaccines and infertility) or a responsibility for others (e.g., a teacher seeking to make a classroom safe), press (both local and national), trade unions (e.g., for health and care workers) and journalists, politicians and policymakers from the United Kingdom and abroad

As the group became established, the aim of Independent SAGE became clearer: to scrutinize and communicate the best available scientific evidence; to listen to the experiences, concerns and perspectives of diverse members of the public; and to put these together in ways that would support those faced with difficult decisions. Many questions raised issues that we were not sufficiently expert to tackle (e.g., how best to control indoor air quality, support for mental health of young people), so we used those as prompts to seek additional expert guest speakers on the briefings. These individuals were selected based on their scientific reputation and publications and their willingness to enter into direct dialogue with the public.

Some members were involved in both Independent SAGE and official governmental SAGE, and gave the same advice in each setting. The main differences lay in whether and how they engaged with the public in these respective roles.

From mid-2020 to late 2023, briefings by Independent SAGE were broadcast live on YouTube and Twitter. The Citizens developed and supported the Independent SAGE website (www.independentsage.org) and Twitter account (@independentsage), facilitated the weekly briefings and fielded questions from the public and media enquiries. An example of the weekly briefing is described in Box 1.

Independent SAGE also produced numerous written outputs, shared on their website. These included downloadable reports and policy recommendations, short statements on emerging topics, fact sheets, visualizations (e.g., accessible graphs and diagrams) and a collection of short-format ‘myth-busting’ videos. Its members frequently contributed to broadcast and printed national and international media, as well as engaging on social media.

Independent SAGE came to be seen by many as an accessible and timely source of evidence-based advice and information, both inside the United Kingdom and internationally28. Its reports were cited and members quoted across the full range of both broadsheet and tabloid press, as well as in the UK Parliament and legislatures of the devolved nations (Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland).

Perceived impact of Independent SAGE

We were not resourced to comprehensively measure the impact of our activities and indeed because we were operating in a complex and fast-changing open system, this would have been difficult even if resources had been available. From a metrics standpoint, Independent SAGE produced ~150 weekly live briefings (all of which are recorded and archived on YouTube), over 50 in-depth scientific reports, 16 mythbuster videos and made over 500 appearances on live television and radio. At the height of the pandemic, for example, well over 100,000 people watched our live-streamed briefing every week (e.g., over 200,000 views for the 30 December 2020 briefing)29,30. Independent SAGE’s feed on Twitter/X attracted over 170,000 followers. Informal feedback from the lay public indicated strong support for our interactive sessions where they could put questions directly to us in real time. The weekly ‘numbers’ slot, in which experts presented figures graphically, explained their significance and discussed the associated uncertainties, was extremely popular. Subgroups of the population greatly valued our work on particular issues (e.g., those planning or going through a pregnancy appreciated nuanced discussions on the risks and benefits of COVID vaccines in pregnancy).

In addition, our collaborative activities with advocacy groups and unions generated a number of tangible outputs. For example, collaboration with health and safety specialists and trade unions drove two initiatives aimed at emphasizing, illustrating and signposting the need for infection-resilient environments in allowing safe return to schools, universities and workplaces. The ‘scores on the doors’ plan saw the design of clear signage to indicate the air quality within indoor spaces as well as their appropriate safe use. Later, the ‘COVID pledge’ (a manifesto for safe workplaces) expanded on infection resilient environments by involving multiple charities, trade unions and other stakeholders in the commitment to ensure all members of the public would have the best possible access to healthy indoor environments31. This initiative also contributed to the Scottish Government’s policy on clean indoor air.

Winding down the Independent SAGE initiative

The Independent SAGE group was assembled in response to the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nobody at the time knew how long it would be needed for. As the pandemic developed, Independent SAGE expanded, with additional experts joining from disciplines including virology, immunology, primary health care and social sciences.

Membership of Independent SAGE was entirely voluntary and unpaid, undertaken in addition to each member’s day job. At the height of the early pandemic, preparation for the weekly briefing could involve several days’ work, especially for a member presenting ‘the numbers’ or the special topic. Members balanced this in different ways, sometimes by aligning their Independent SAGE work with their remunerated day job and sometimes by carving out time outside office hours. To some extent, the global camaraderie of scientists responding to the pandemic energized us. Over time, however, some members stepped down, almost always because they were unable to commit further to the time required. Inevitably, in a situation characterized by considerable uncertainty with decisions that require complex trade-offs, there were some disagreements among members. These could almost always be reduced (though not always fully resolved) by discussion, though on one occasion, an unresolved disagreement precipitated a member’s decision to leave the group.

After more than 3 years of weekly briefings, and as COVID-19 transitioned from an acute to a long-term public health challenge, the sense of crisis diminished. In addition, many members had a backlog of other commitments that had been put on hold. While the group had not formally disbanded, the live weekly briefings moved to every 2 weeks in spring 2023 and ended in December 2023. The group established a Substack channel (‘Independent SAGE Continues’) and they are still in close contact with one another through social media channels and occasional online or in-person meetings.

Learning points from Independent SAGE’s development

As a voluntary unofficial group, Independent SAGE had a collegiate culture and little internal hierarchy, although chairs were assigned to oversee preparatory meetings and host the live sessions. Whilst this ethos of informal, nonbureaucratic scientific dialogue remained as the group grew and matured over time, several learning points emerged across scientific, ethical, practical and operational domains. We hypothesize that these learning points (which broadly reflect academic literature on science–public and science–policy dialogue1,18,32,33) are likely to be applicable, to some extent and with modification, to other public health emergencies. Importantly, however, the points should not be seen as a universal formula or blueprint, but rather as guiding principles. Independent SAGE emerged in a particular country at a particular time in response to a unique set of circumstances and events. Other emergencies, in other settings, will have their own priorities and constraints.

Clarity and transparency

High-quality science communication in a pandemic involves conveying complex concepts (e.g., the nature of viruses and their evolution, data on cases and transmission) effectively to a very large lay audience. This task is complicated when false or contradictory evidence is freely circulating, often without being contextualized. Clear and concise messages, supported by visual representations of data, are key. Public trust18,32 in science and science-based policy is diminished by secrecy, whereas it increases when both facts and uncertainties are openly shared with the public34,35,36,37,38.

It is also important to convey the estimated level of uncertainty around a scientific question or issue (a task on which much has been written34,35,38) and, where appropriate, to change position in the light of new evidence rather than sticking to one that was reached before key evidence was available. For example, we were initially cautious about the early proposals for repeated mass testing using lateral flow tests, given that the available documentation on what was termed a ‘Moonshot’ project was strong on ambition but deficient in detail. As improved tests became available, we revisited the evidence base and after reviewing data on test performance and experience in other countries, came to a more favorable conclusion.

Independent SAGE was also transparent about its collective values: it advocated for evidence-based policy that protected lives, reduced pressure on health services and took into account social influences on and consequences of health decisions. Members were asked to declare any conflicts of interest and agree to follow a code of conduct when they joined.

Engaging with the science–policy interface

The maxim ‘scientists advise, ministers decide’ overlooks how, in reality, policymaking (and especially crisis policymaking) requires a dialogue between scientists and policymakers2,39. Scientists must not only convey research findings, but also explain why they matter; what is at stake; how a situation is likely to unfold with, or without, implementing a particular policy; and how to implement scientific insights in ways that will be effective in achieving the desired ends. Policymakers must make clear to scientists that, in addition to academic concerns, they must take into account expectations, practical constraints, timescales and cost implications for key decisions, thus producing a two-way dialogue on the realities of implementing the best scientific practices4,39.

David Easton—an early advocate of systems theory in political sciences—defined policymaking as “the authoritative allocation of values for the whole of society”40. Under that premise, scientific ‘facts’ can be value laden in the sense that they can be mobilized rhetorically to support or advise against particular policies7. Independent SAGE sought to present scientific data not in a value-free bubble, but as inextricably tied to the values that informed particular policy options. Sometimes this meant challenging the government on policies that we did not consider evidence based or risked causing harm, such as when lifting all restrictions in the name of ‘freedom’, a decision that (in our view) placed vulnerable groups at risk.

Interdisciplinarity

In a fast-unfolding public health crisis, scientists and other scholars from a range of backgrounds and disciplines need to work together and understand each other. For example, questions about potential individual- and population-level impacts of the virus touched on genetics, medicine, immunology, virology, evolutionary biology, ecology, behavioral sciences, mathematical modeling, public health, actuarial sciences and sociology. New research findings from genetics, immunology or other fundamental science might suggest that a change in individual behavior is needed, requiring input from the behavioral and social sciences (e.g., strategies for building trust in science41 or addressing the reasons for vaccine hesitancy42).

Independent SAGE members covered a deliberately wide range of expertise and, because of interdisciplinary insights, the group’s outputs were more than the sum of its parts. Interdisciplinarity played out partly through allocation of topics and tasks (certain people were clearly experts on particular subjects and methods such as mathematical modeling) and also through group dialogue (as we discussed a multifaceted topic it sometimes became clear that an additional disciplinary lens was needed, for example, the psychology of how people interpret models). An example of an interdisciplinary output is our early report on test/trace/isolate, which drew on our collective expertise in public health, virology, addressing inequalities, behavioral science, communication and health policy43.

As the group worked together, each member developed a clearer understanding of how their own scientific contribution complemented that of other members, allowing us to draw flexibly on each other’s expertise and form small ad hoc working groups for particular reports and presentations. As noted above, if a particular discipline was needed for a topic but not present within the group, we invited an external expert.

One of the benefits of having an open multidisciplinary dialogue within Independent SAGE was the ability to counteract biases or tunnel vision that researchers may develop when focused on a narrow topic of interest. While individual members of Independent SAGE may each have their own positions, an open discussion of alternative points of view ultimately ensured that the group’s output remained balanced. These interdisciplinary challenges were further enhanced by regular live interaction with a broad range of lay people.

Addressing inequality

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing inequalities throughout society44,45. It disproportionately affected various marginalized and vulnerable groups including those in deprived areas, Black and minority ethnic communities, those with learning difficulties and clinically vulnerable people. Similarly, the COVID-19 response affected these groups in different ways, and policymakers’ failure to acknowledge this and mitigate against it (for example, by failing to provide learning resources to all children during school closures) only exacerbated those inequalities. From the earliest days of the pandemic, Independent SAGE were concerned that its impact would fall disproportionately on more vulnerable groups. We explicitly and proactively advocated for the cause of many such groups and featured their voices and experiences in many of the live sessions. One of our first ever reports was on the disproportionate number of Black and minority ethnic deaths from COVID-19 in early 202046.

More generally, we repeatedly raised the pervasive issue of inequalities both in written academic reports47,48 and in dedicated live sessions featuring expert guest speakers, including one on links between socio-economic deprivation and COVID-19 with Professor Michael Marmot and Debbie Abrahams MP49, and another on inequalities with Professors Clare Bambra and Arpana Verma50. We wrote many articles for the general press on the importance of welfare support (such as sick pay). We raised concerns both in our independent reports51 and in academic journals about vaccine inequity52,53. We covered the pandemic’s impact on children and young people and called for more action—including vaccination and attention to indoor air quality—to protect them54,55.

Interaction and dialogue with the public

Independent SAGE’s commitment to respecting and involving the public contrasted with a government response, which (some argue) saw the public as a problem56. Treating the communication of the different aspects of the scientific discourse as a genuine dialogue helped ensure that multiple voices were heard. This commitment to an open dialogue with the public reflects what has been termed ‘mode 2 science’—occurring, at least in part, outside the walls of the university33. This involves reflection on the role and ethical significance of science in society and celebrating the ‘agora’ (public space) where democratic discussion between scientists and the public occurs33,39. Some of these dialogues were brief and focused on information giving, such as answering questions posed by the public in our weekly briefings (e.g. “should I have the Astra Zeneca vaccine I’ve been offered or shop around for a different one?”), though not infrequently these questions promoted us to produce resources such as factsheets (e.g., on vaccination in young people), animations (e.g., on indoor air quality) or brief videos (e.g., our ‘mythbusters’ series). Other dialogues consisted of ongoing and collaborative interactions with groups or organizations.

Supporting advocacy and interest groups

‘The public’ and other bodies include well-informed and committed groups with particular expertise and/or interests on a variety of issues. Parents, for example, want schools to be safe. Trade unions seek to secure safe working conditions for their members. Members of Parliament have a duty to raise questions on behalf of their constituents. Clinically vulnerable people and their loved ones know that safe public spaces can be a matter of life or death. Long COVID sufferers understand how important research into the condition is. We found that early and respectful dialogue with such groups could hone the key questions that needed answering and create effective channels for disseminating key findings. Conversely, advocacy and pressure groups found that engaging with a group of respected scientists such as Independent SAGE increased their visibility and credibility. We worked with numerous groups, including:

-

Long COVID patient support groups

-

Clinically Vulnerable Families57, a network to support immunosuppressed, frail or those with multiple health conditions that may impair immunity, and who became core participants in the UK COVID-19 Inquiry

-

COVID-19 Bereaved Families for Justice, a UK pressure group fighting to ensure that the mistakes of the COVID-19 pandemic are never repeated

-

Trade unions (e.g., Unite, the leading workers’ union in United Kingdom and the Scottish Trade Union Congress) and worker support groups (e.g., Hazards, Doctors in Unite) to develop the COVID Pledge described above31

In some of these collaborations, the mode of interaction might legitimately be described as coproduction of outputs with advocacy and interest groups rather than production of resources for those groups.

Multiple communication channels and modalities

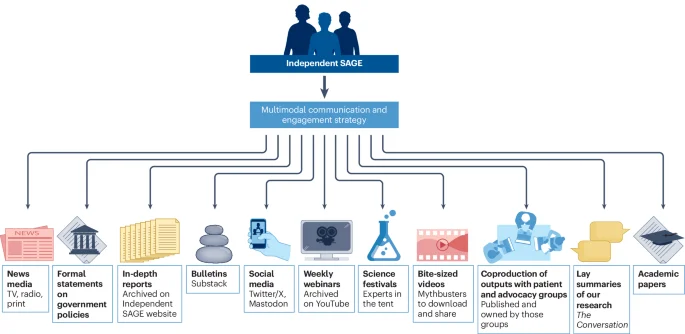

Different sectors of the population get their information from a wide range of different sources and in different formats. Independent SAGE members, facilitated by The Citizens, proactively engaged with diverse knowledge outlets, including social media microblogging sites (Twitter/X, Mastodon, Bluesky, YouTube), longer blogs, public-facing academic platforms such as The Conversation58,59, bulletins, podcasts and mainstream broadcast and print media (Fig. 1). Alongside the weekly live briefings, social and traditional media, Independent SAGE members also produced (for example) scripted team presentations as YouTube videos and video clips, blogs, infographics and animations. Members also wrote accessible papers and books aimed at a broad scientific and practitioner audience. Examples are given in Table 1.

Independent SAGE developed its relationship with the public via a broad range of complementary communication modalities. Transmitting across channels enabled to streamline the information for different audiences and helped widen the reach of Independent SAGE, reinforcing both the group’s learning ability and its science communication efforts.

Regular and organized internal communications

The scientists in the group did not have to publicly agree on every issue on every occasion, but they did spend time deliberating collectively on the significance of emerging data and learning from each other. For Independent SAGE, this ‘backstage’ activity typically occurred in prebriefing meetings and discussions via videoconference. These informal meetings facilitated scrutinizing content, setting the tone for forthcoming public presentations, allocating tasks, sharing ideas for guest speakers, flagging and dealing with concerns, shaping the collective identity and affirming its shared values.

A good example of this was how we prepared for a special briefing 1 year on from the United Kingdom’s ‘Freedom Day’ (19 June 2021, the day the UK dropped most protective measures) by considering various angles to cover (the impact on the incidence of COVID-19, the impact on clinically vulnerable people, sickness absence among health care staff, pressure on services, risk of emergence of new variants) and the disciplinary expertise needed to address them (modeling, statistics, clinical medicine, public health, evolutionary virology). Our ‘backstage’ meetings also provided shared learning and support for members who experienced abuse on social—or indeed traditional—media or via email. This experience was far more common for the women (particularly women of color) in the group and those promoting the scientific evidence on issues that became politicized, such as facemasks and vaccines. The rich internal communications helped members become more rounded commentators, able to field questions beyond their immediate expertise, for example, by acknowledging the importance of the topic and providing a steer as to what kind of expert would be needed to answer the question in more detail.

Resourcing and supporting the group communications

Even when scientists give their time for free, financial and human support is needed to run a website, stage live digital briefings, process questions and comments from the public, and make reports and publications accessible. ‘Amateur’ media clips such as short Tik-Tok videos have some advantages by being able to be made quickly, cheaply and may humanize the scientists. However, there is also a place for professional-quality multimedia presentations that can be showcased to policy audiences and widely shared across multiple platforms. Technical support for making such presentations can be costly, but if the scientists have national reach, crowdfunding is a possible source of support. Independent SAGE used two crowdfunder exercises to raise relatively modest sums (£15,000–20,000 each time) to continue supporting briefings and communication activity in 2022 and 2023. In each case, the crowdfunders were closed after a few days due to the rapid and generous responses. Fundraising efforts should be clear, transparent and focused as people need to know what will be done with any donations. These approaches can also enable the public and scientists to feel joint ownership of the collective endeavor.

Combating misinformation and disinformation

Pandemics provide fertile soil for misinformation (unintentionally misleading information) and disinformation (deliberate falsehoods)60,61, which potentially subvert the choices made by individuals or by society collectively. Behavioral and social scientists in Independent SAGE provided evidence-based strategies for responding to false and misleading information62. These included providing consistent and accurate messages, being honest if in doubt, communicating uncertainty, producing diagrams and infographics and tailoring messages to different social and cultural groups. One specific initiative we undertook was preparing 16 ‘mythbuster’ videos on topics (such as the benefit–harm balance of vaccines) that were characterized by mis/disinformation (Table 1).

Critical reflections on the Independent SAGE approach

The model of communication used by Independent SAGE had many strengths and (we believe) provided an important contribution to the science–policy ecosystem at a critical time. But it was not perfect and, in retrospect, there are things we would have done differently.

The name ‘Independent SAGE’ was chosen somewhat hastily and without full consideration of the consequences. In its favor, the name conveyed both authority (it was a ‘scientific advisory group’) and independence (of the UK Government), thus distinguishing it from official SAGE. But the name led to confusion among the lay public (some people assumed we were part of the official advisory process, while others believed the group was set up in opposition to official SAGE) and caused some offense in official circles. The confusion was perhaps exacerbated by the fact that three members of Independent SAGE also sat on a subgroup of official SAGE and, in many cases, both groups were putting out similar or identical advice, and Independent SAGE outputs often drew on SAGE reports. In hindsight, a different name might have been better.

The slogan ‘following the science’ was also somewhat ambiguous. The definite article (‘the’) implied that there was one (value-free) science that just needed to be identified and summarized, whereas the reality was of multiple scientific and science-related questions that were often value laden and could be framed in various ways, multiple streams of potentially relevant evidence on which there was little or no consensus among experts, and multiple implications of that body of evidence for different policy decisions. On reflection, a less definitive strapline such as ‘scrutinizing science policy’ might have been better.

We did not sufficiently clarify how wide our remit was in terms of topics. The clinical, epidemiological, virological, immunological, behavioral science and public health aspects of COVID-19 were clearly in scope for Independent SAGE, but there was ambiguity (for example) about how far we should engage with the impact of the pandemic on the economy, the ethics of crisis policymaking or the influence of political affiliation on policy decisions. As the pandemic played out, we made various decisions on how to cover these issues and invited various experts onto the weekly briefings to be interviewed by us. But, notwithstanding the need to adjust our aims in response to a changing situation, it might have been better to have set clearer boundaries on our remit early in the pandemic, or at least been clearer when remits changed or broadened over time.

While we addressed misinformation and disinformation about COVID-19, we were, perhaps, insufficiently proactive in responding to misleading information and deliberate untruths about Independent SAGE and its members. A leading UK medical journal depicted us as ‘rebel scientists’, implying (incorrectly) that our views were radical and heterodox63. Some people incorrectly depicted us as politically motivated and wedded to particular extreme policies (such as pursuing an uncompromising ‘zero COVID’ agenda, which included closing all schools, extending lockdown and imposing universal masking). In fact, our position on all these topics was far more nuanced. For example, we argued that targeted quarantine, test-and-trace, masking and attention to air quality might be adopted judiciously to help avoid school closures or prolonged lockdowns. In retrospect, we could have done more to make that nuanced position clearer and actively address the malicious caricatures propagated by some of our critics.

A final limitation of our work at Independent SAGE is that, as noted above, we did not formally set out to measure the impact of our work, and this goal was probably not realistic given our prevailing circumstances (e.g., having demanding full-time jobs) and resources (we were reliant on crowdfunding). In the future, we believe it would be worthwhile to anticipate the need for independent research on the role of informal actors in the science–policy ecosystem. Owing to the nature of this ecosystem (multiple actors emerging, responding and influencing one another), deterministic study designs seeking to measure the impact of actor X on outcome Y are unlikely to be helpful. But it should be possible to develop system-oriented mixed-method designs that can begin to tease out the strengths, contribution and synergies (as well as the limitations and caveats) of different kinds of actor, official and unofficial, in this complex ecosystem.

Conclusions

Global public health crises provide unique conditions for innovation in how scientific findings are debated and explained to a lay audience and among experts across disciplines. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way scientists and policymakers work together to produce evidence-based decisions in crisis situations and it has provided the impetus for developing innovative models for visualizing and explaining emerging scientific findings to the public in real time. This is essential because the often-complex science has far-reaching implications for individual lives and freedoms and individuals wish to exercise agency in moments of crisis.

We believe that the informal approach taken by Independent SAGE, applied adaptively to different contexts and situations, has much to offer in public health crises as part of a wider knowledge ecosystem of scientific and policy actors. Such informal models are designed to progress the science–policy–public dialogue in ways that complement (and, where appropriate, challenge) official structures and positions. In some ways, for example, official SAGE existed to provide formal advice that informed policy, whereas Independent SAGE existed to provide informal advice that could include challenging policy.

While honesty and transparency are important rules of thumb, questions such as “what level of secrecy should official scientific advisory bodies follow during fast-unfolding pandemics?”, “how much scientific and policy uncertainty should be shared with the public?” or “from whom, if anyone, should governments seek advice in addition to their official advisors?” cannot be answered definitively or for all time, we believe that in any particular unfolding crisis, such questions should be kept alive through vigorous public debate to which scientists can, and should, contribute.

In situations where the stakes are high, the facts uncertain, the values in dispute and the need for decisions urgent, it is more important than ever that scientists engage directly and democratically with the public. Their role must surely be to present the state of knowledge, ignorance and uncertainty on issues of the day, to support, inform and engage with the public, link with a wide range of advocacy and campaign groups and—where necessary—speak truth to power.

References

-

McKee, M. et al. Open science communication: the first year of the UK’s Independent Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies. Health Policy 126, 234–244 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Boin, A., Stern, E. & Sundelius, B. The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership under Pressure (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2016).

-

The Precautionary Principle: Decision Making under Uncertainty https://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/precautionary_principle_decision_making_under_uncertainty_FB18_en.pdf (European Commission, Brussels, 2017).

-

Michie, S., Ball, P., Wilsdon, J. & West, R. Lessons from the UK’s handling of COVID-19 for the future of scientific advice to government: a contribution to the UK COVID-19 public inquiry. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 17, 418–433 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Koch, N. & Durodié, B. Scientists advise, ministers decide? The role of scientific expertise in UK policymaking during the coronavirus pandemic. J. Risk Res. 25, 1213–1222 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Bauer, M. S., Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H., Smith, J. & Kilbourne, A. M. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 3, 1–12 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Weiss, C. H. The many meanings of research utilization. Public Adm. Rev. 39, 426–431 (1979).

Google Scholar

-

Oliver, K. & Cairney, P. The dos and don’ts of influencing policy: a systematic review of advice to academics. Palgrave Commun. 5, 1–11 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Shiffman, J. & Smith, S. Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. Lancet 370, 1370–1379 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Freedman, L. Scientific advice at a time of emergency. SAGE and COVID‐19. Political Q. 91, 514–522 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Colman, E., Wanat, M., Goossens, H., Tonkin-Crine, S. & Anthierens, S. Following the science? Views from scientists on government advisory boards during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative interview study in five European countries. BMJ. Glob. Health 6, e006928 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Goddard, N., Delpech, V., Watson, J., Regan, M. & Nicoll, A. Lessons learned from SARS: the experience of the Health Protection Agency, England. Public Health 120, 27–32 (2006).

Google Scholar

-

Report: Exercise Alice Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Public Health England, 2016).

-

Hine, D. Independent Review into the Response to the 2009 Swine Flu Pandemic https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-into-the-response-to-the-2009-swine-flu-pandemic (UK Cabinet Office, 2010).

-

Han, E. et al. Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 restrictions: an analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. Lancet 396, 1525–1534 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Pearce, W. Trouble in the trough: how uncertainties were downplayed in the UK’s science advice on Covid-19. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 7, 122 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Tyler, T. R. Why People Obey the Law (Princeton Univ. Press, 2006).

-

Cairney, P. & Wellstead, A. COVID-19: effective policymaking depends on trust in experts, politicians, and the public. Policy Des. Pract. 4, 1–14 (2021).

-

Weinberg, J. Trust, governance, and the COVID‐19 pandemic: an explainer using longitudinal data from the United Kingdom. Political Q. 93, 316–325 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Fancourt, D., Steptoe, A. & Wright, L. The Cummings effect: politics, trust, and behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 396, 464–465 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Enria, L. et al. Trust and transparency in times of crisis: results from an online survey during the first wave (April 2020) of the COVID-19 epidemic in the UK. PloS ONE 16, e0239247 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Newton, K. Government communications, political trust and compliant social behaviour: the politics of COVID‐19 in Britain. Political Q. 91, 502–513 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Capodici, A., Salussolia, A., Sanmarchi, F., Gori, D. & Golinelli, D. Biased, wrong and counterfeited evidences published during the COVID-19 pandemic, a systematic review of retracted COVID-19 papers. Qual. Quant. 57, 4881–4913 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Scheinerman, N. & McCoy, M. What does it mean to engage the public in the response to covid-19? BMJ. 373, n1207 (2021).

-

Independent SAGE. Indie_SAGE 04.05.20 – first committee meeting. Independent SAGE Youtube Archive https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L7uBwyr0sdg (2020).

-

Independent SAGE. Independent SAGE 22nd May interim report on schools. Independent SAGE YouTube Archive https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=32OFgfH17KU (2020).

-

Independent SAGE. Independent SAGE 09.06.20. Independent SAGE YouTube Archive https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g34W-j9h0nI (2020).

-

Rajan, S. et al. In the Wake of the Pandemic: Preparing for Long COVID Policy Brief No. 39 (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021).

-

Independent SAGE. Independent SAGE is calling for an immediate national lockdown. Independent SAGE Twitter Feed https://x.com/IndependentSage/status/1344222227961548800?s=20 (2020).

-

Independent SAGE. Independent SAGE public briefing 30th December. Independent SAGE YouTube Archive https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kIcCUY5vWc (2020).

-

The COVID-19 safety pledge. COVID Pledge https://covidpledge.uk (2022).

-

Pielke, R. A. The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007).

-

Nowotny, H., Scott, P. B. & Gibbons, M. T. Re-thinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty (Wiley, 2013).

-

Van Der Bles, A. M. et al. Communicating uncertainty about facts, numbers and science. R. Soc. Open Sci. 6, 181870 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Fischhoff, B. & Davis, A. L. Communicating scientific uncertainty. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13664–13671 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Warren, G. W. & Lofstedt, R. Risk communication and COVID-19 in Europe: lessons for future public health crises. J. Risk Res. 25, 1161–1175 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Rajan, D. et al. Governance of the COVID-19 response: a call for more inclusive and transparent decision-making. BMJ. Glob. Health 5, e002655 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Renn, O. et al. Making Sense of Science for Policy under Conditions of Complexity and Uncertainty https://doi.org/10.26356/MASOS (Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (SAPEA), 2019).

-

Greenhalgh, T. & Engebretsen, E. The science-policy relationship in times of crisis: an urgent call for a pragmatist turn. Soc. Sci. Med. 306, 115140 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Easton, D. The Political System (Knopf, 1953).

-

Rolin, K. in The Routledge Handbook of Trust and Philosophy (ed. Simon, J.) 354–366 (Routledge, 2020).

-

Machingaidze, S. & Wiysonge, C. S. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nat. Med. 27, 1338–1339 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

A Blueprint to Achieve an Excellent Find, Test, Trace, Isolate and Support System https://www.independentsage.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/New-FTTIS-System-final-06.50.pdf (Independent SAGE, 2020).

-

Scambler, G. COVID-19 as a ‘breaching experiment’: exposing the fractured society. Health Sociol. Rev. 29, 140–148 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Bambra, C., Lynch, J. & Smith, K. E. The Unequal Pandemic: COVID-19 and Health Inequalities (Bristol Univ. Press, 2021).

-

Disparities in the Impact of COVID-19 in Black and Minority Ethnic Populations: Review of the Evidence and Recommendations for Action (Report 6) https://www.independentsage.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Independent-SAGE-BME-Report_02July_FINAL.pdf (Independent SAGE, 2020).

-

Douglas, M., Katikireddi, S. V., Taulbut, M., McKee, M. & McCartney, G. Mitigating the wider health effects of covid-19 pandemic response. BMJ. 369, m1557 (2020).

-

COVID-19 and Health Inequality (Report No. 21) https://www.independentsage.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Inequalities-_i_SAGE_FINAL-draft_corrected.pdf (Independent SAGE, 2021).

-

The COVID-19 Crisis and Inequalities. Independent SAGE Weekly Briefing 4th March 2022 https://www.independentsage.org/weekly-briefing-4th-march-2022/ (Independent SAGE, 2022).

-

COVID-19 and the Implications for Health Inequalities. Independent SAGE Weekly Briefing 9th December 2022 https://www.independentsage.org/weekly-briefing-9th-dec-2022/ (Independent SAGE, 2022).

-

How to Achieve Global Vaccine Rollout. Report No. 35 https://www.independentsage.org/how-to-achieve-global-vaccine-rollout/ (Independent SAGE, 2021).

-

Burgess, R. A. et al. The COVID-19 vaccines rush: participatory community engagement matters more than ever. Lancet 397, 8–10 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Haque, Z. Vaccine inequality may undermine the booster programme. BMJ. 375, n3118 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Gurdasani, D. et al. Vaccinating adolescents against SARS-CoV-2 in England: a risk–benefit analysis. J. R. Soc. Med. 114, 513–524 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Gurdasani, D. et al. Mass infection is not an option: we must do more to protect our young. Lancet 398, 297–298 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Coronavirus: Lessons Learnt To Date (Health and Social Care Committee and Science and Technology Committee, 2022).

-

Clinically Vulnerable Families https://www.clinicallyvulnerable.org/ (accessed 8 November 2024).

-

Greenhalgh, T., Jimenez, J.-L., Milller, S. & Peng, Z. Here’s where (and how) you are most likely to catch COVID—new study. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/heres-where-and-how-you-are-most-likely-to-catch-covid-new-study-174473 (2022).

-

Michie, S. et al. New COVID variants have changed the game, and vaccines will not be enough. We need global ‘maximum suppression’. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/new-covid-variants-have-changed-the-game-and-vaccines-will-not-be-enough-we-need-global-maximum-suppression-157870 (2021).

-

Iyengar, S. & Massey, D. S. Scientific communication in a post-truth society. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7656–7661 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Lee, C., Yang, T., Inchoco, G. D., Jones, G. M. & Satyanarayan, A. Viral visualizations: how coronavirus skeptics use orthodox data practices to promote unorthodox science online. In Proc. 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 1–18 (ACM, 2021).

-

Ecker, U. K. et al. The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 13–29 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Clarke, L. COVID-19’s rebel scientists: has iSAGE been a success? BMJ. 375, n2504 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Signs and ‘Scores on the Doors’: Communicating About Ventilation https://www.independentsage.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Independent-SAGE-SotD-March-2022-FINAL-3-1.pdf (Independent SAGE, 2022).

-

Statement on the Management of NHS Test and Trace https://www.independentsage.org/statement-on-the-management-of-nhs-test-and-trace/ (Independent SAGE, 2020).

-

Independent SAGE Statement on the UK Government’s Roadmap for Ending All Restrictions https://www.independentsage.org/indie-sage-statement-on-the-uk-government-roadmap-for-ending-all-restrictions/ (Independent SAGE, 2021).

-

Independent SAGE. Vaccines, variants and immunity. Independent SAGE 1st July 2022. Independent SAGE YouTube Archive https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a3ymXVpE8Lc (2022).

-

Katzourakis, A. COVID-19: endemic doesn’t mean harmless. Nature 601, 485–485 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Pagel, C. & Yates, C. Role of mathematical modelling in future pandemic response policy. BMJ. 378, e070615 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Independent SAGE. A seven point plan to suppress covid infections and reduce disruptions. BMJ. 378, o1793 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Cruickshank, S. COVID-19 immunity: how long does it last? The Conversation https://theconversation.com/covid-2019-immunity-how-long-does-it-last-152849 (2021).

-

Williams, S. N. & McKee, M. How austerity made the UK more vulnerable to COVID. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/how-austerity-made-the-uk-more-vulnerable-to-covid-208240 (2023).

-

Yates, K. ‘The models were always wrong’ (Independent SAGE Mythbuster series no. 5). YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QQkjMb0-d3g (2022).

-

Pagel, C. ‘It’s lockdown or nothing’ (Independent SAGE Mythbuster series no. 4). YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=02zgVKXptDI (2022).

-

Cruickshank, S. ‘Vaccines were rushed through’ (Independent SAGE Mythbuster Series 7). YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yZl47u8psXw (2022).

-

Independent SAGE at BlueDot. BlueDot https://discoverthebluedot.com/profile/indie-sage/ (2023).

-

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Coronavirus. Evidence session: easing of restrictions. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bOWUW55wMPU (2022).

-

English, C. Ripples: the forgotten 500,000. Spotify https://open.spotify.com/show/2c3b8fVp1JTWAGPbFniAiX (2022).

-

Pagel, C. The Astra Zeneca vaccine saved millions of lives globally. Substack https://christinapagel.substack.com/p/the-astra-zeneca-covid-vaccine-saved (2024).

-

Independent SAGE. COVID-19 situation report, May 2024. Substack https://independentsage.substack.com/p/covid-situation-report-may-2029-2024 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support, collaboration and intellectual input from other current and previous members of Independent SAGE, and from numerous additional scientists and advocates who have acted as advisors, guest speakers and critical friends to Independent SAGE the past few years. We thank C. Cadwalladr for her inspiration and energy in initiating Independent SAGE, and The Citizens for their unfailing support and guidance on how best to communicate complex science to (and with) diverse audiences. Finally, we thank patients and the public—both individuals and groups—for their crucial input to ongoing debates about science and how science should influence policy. The authors, who are all current members of Independent SAGE, thank all current and former colleagues on Independent SAGE for interdisciplinary and collegial dialogues, which have shaped and enriched their thinking. A fill list of past and present members of Independent SAGE is available at https://www.independentsage.org/who-are-independent-sage/. Responsibility for the present article, including any errors or omissions, rests with the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors are members of Independent SAGE. T.G. is an unpaid advisor to the philanthropic group Balvi. M.M. is Past President of the British Medical Association and European Public Health Association, Research Director of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policy, a partnership of governments, international agencies, and universities, and an advisor to the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Director for Europe. He is a former chair of WHO Europe’s Advisory Committee on Health Research and a former member of the European Commission’s Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health. He is a current member of the Advisory Committee of Friends of the Global Fund Europe and the European Health Forum Gastein and is President of the European Public Health Conference Foundation. S.M. participated in the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group in Emergencies (SAGE) and its behavioural science sub-group, ‘SPI-B’. S.R. is a member of the UK’s Independent Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviours and the Scottish Government COVID-19 Advisory Group. A.R. is a freelance broadcaster and author and Past President and current Vice-President of Humanists UK.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Protocols thanks Nicole Grobert, Tommi Kärkkäinen, Jaakko Kuosmanen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greenhalgh, T., Costello, A., Cruickshank, S. et al. Independent SAGE as an example of effective public dialogue on scientific research.

Nat Protoc (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-024-01089-6

-

Received: 05 June 2024

-

Accepted: 08 October 2024

-

Published: 12 December 2024

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-024-01089-6