How do you make a museum show about Indigenous culture when the very idea of the museum, an invention of European enlightenment, has its roots in colonialism? This question rumbles behind but is never quite resolved in Indigenous Histories, the new show at Museu de Arte de São Paulo. It is also central to an indicative work in the exhibition: Peruvian artist Susana Torres’s decision in 1999 to start collecting and exhibiting commercial products and consumer packaging featuring Inca imagery.

The curators at MASP present just one such example from Torres’s Museo Neo Inka series (1999-2011): a sack of wheat flour that shows the head of an Inca man printed above the legally required nutritional table. For Torres it was ironic that the marketing people behind the flour, and brands such as Inca Kola (created by a British man in the 1930s) and Inca cigarettes (a favourite of poet Allen Ginsberg), were using the imagery to invoke a sense of tradition, while contemporary Peruvian Indigenous people were economically maligned and cut from the cultural conversation.

If this sprawling exhibition of 170 artists is an attempt to correct that, bringing Indigenous production into the canon, then it is certainly ambitious in its geographical spread. Programmed in collaboration with Norway’s Kode Bergen Art Museum, where the show travels next year, it is divided into eight sections: seven devoted to regions in South America, North America, Oceania and Scandinavia, as well as a first room for pan-global examples of Indigenous resistance to colonialism and capitalist exploitation.

It opened as Australians voted against recognising Aboriginal communities and Torres Strait Islanders in the country’s constitution and guaranteeing them a voice in decision-making but also as, more positively, Brazil’s supreme court rejected a law limiting what might be considered Indigenous peoples’ land. Indigenous issues are live today.

In the global room, a 2012 photograph by Alexander Luna feels symbolic of this never-ending fight for first peoples’ rights. It shows Máxima Acuña dressed in the traditional clothing of the Peruvian Andes, holding her fist aloft. Acuña is smiling, but her story is deadly serious. In the years after the portrait was taken, Acuña faced legal proceedings from American gold-mining company Newmont Corp, which said her home illegally occupied land it had purchased for a new development. She also claims to have been assaulted by Peruvian police after eviction proceedings began. Her torment only ended after a higher court found in her favour and stopped her eviction.

The activist’s tale is a particularly dramatic one, but it is a similar fight for survival that unites the disparate communities present in the rest of the show. Just above Luna’s photograph is the Tino Rangatiratanga Flag (1990), designed by Linda Munn, Hiraina Marsden and Jan Dobson as a symbol of Māori struggle in New Zealand; on facing walls are posters by Arvid Sveen illustrating Sámi political consciousness across Norway and Sweden. Documentary photography by Edgar Kanaykõ Xakriabá shows the Free Land Camp, a meeting of Brazilian Indigenous communities that occupies grounds near government ministries annually.

Inviting guest curators to programme each of the different sections, while pragmatic, means the exhibition loses this initial cohesion. One gallery organised by Mexican artist Abraham Cruzvillegas is packed full of works from the early 20th century, tracing how the representation of Mexican Indigeneity was used to establish a national identity after the revolution of 1910-20. Paintings including “Our Ancient Gods” (1916) by Saturnino Herrán and “Indian Wedding” (c1931) by Alfredo Ramos Martínez are both complementary to Indigenous dignity and exoticising to modern eyes.

From there, the viewer can either enter a gallery of Western Australian “desert painting” or a gallery dedicated to the home culture of Canadian Inuit, First Nations and Métis communities. In the former, Yala Yala Gibbs Tjungurrayi’s “Wirrpi” (1997) is an intoxicating abstract painting of interconnecting ochre, brown and orange orbs, while Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula’s “Mitukatjirri” (1986) displays similarly beguiling patterning.

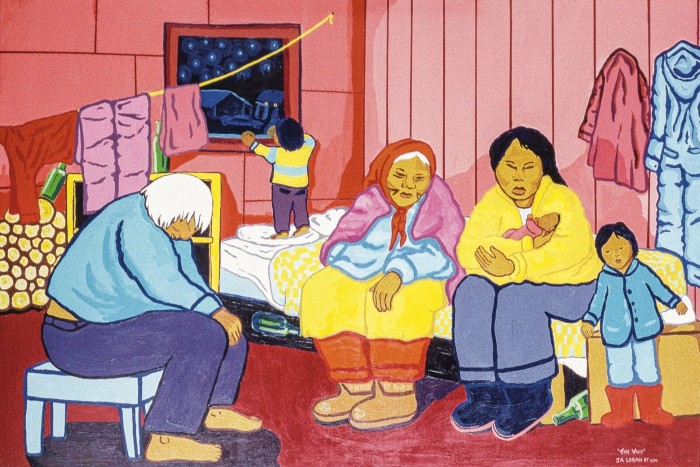

In the latter, Canadian Indigenous artist Jim Logan’s deeply evocative painting “The Visit” (1987) hangs, depicting several generations of a family gather in a single room, wrapped up warm but steeped in poverty, the presence of beer bottles suggesting social problems. Kananginak Pootoogook’s nearby bird’s-eye painting of a boiling pot of berries is more idyllic in sensibility.

All three displays, from the sultry Modernist visions of Mexico to this frozen scene, are strong in their own right, but aside from a common enemy, the connection of these communities, separated by climates, continents and history, is tenuous.

In Brazil it is only in the past few years that artists from Indigenous groups have gained recognition. This year MASP dedicated a survey to the Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin, a collective of artists with Huni Kuin ethnicity from western Brazil. A painting by one member here, Acelino Huni Kuin, shows the “bridge alligator”, a giant creature of myth who lay across the Bering Strait to allow passage between the Americas and Asia, the story subverting notions of the “old” and “new” world. Meanwhile, the stick-figure pen drawings by Taniki Yanomami depict the circularity of birth and death in Yanomami culture. In uncompromising fashion, both present the Indigenous understanding of time as being fundamentally non-linear.

In gaining recognition, however, Indigenous artists have made sacrifices to western art markets. Waxamani Mehinako paints the rhythmic patterns the Xingu peoples traditionally use in body painting, textiles and basketry, but while he uses local pigments, he applies them to canvas, an easier sell within a westernised art market. Maintaining hierarchies of what is art and what is not, just one basketry object is included in the exhibition, a Waláya basket of arumã fibre, by the Bainwa people, but the museum shop is full of lesser examples available to purchase.

The Peruvian artist Sandra Gamarra often hangs her own work, portraits of Spanish colonial nobility, upside down to upset the historic power dynamic between her subject and her Indigenous identity, and tasked with curating a section dedicated to her own country she chose to hang the work similarly. Facing the contemporary Indigenous work, all upside down, is a series of 18th-century oil paintings, only one of which, a Cusco school portrait of St Francisco Javier owned by MASP, is turned on its head. The lenders of the others, a Spanish museum, refused the request on conservation grounds: a signal that for all the progress evident in Indigenous Histories, an important show, if not a perfect one, there is some distance left to run in art’s decolonising mission.

To February 25, masp.org.br

Follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen