London label Jaded just dropped a technicolour rave-ready tribute to cult 90s publication Sleazenation. Curator Jamie Brett talks Teddy boys, emos, and why the link-up feels like perfect timing

It’s time to let bylines be bygones. Sleazenation and Dazed were famously not best-of-friends; Neil Boorman, the then-editor of that former style mag, once quipped about editorials that didn’t make the cut: “We forwarded everything to Dazed as a courtesy, so they might be in touch.” Rumour had it that Sleaze sent its writers to intern at this mag’s HQ and gather intelligence. Is it true? If we told you, we’d have to kill you.

Dazed didn’t take it to heart. This was, simply, the Sleaze way. First issued in 1996 as a club guide by Adam Dewhurst and Jon Swinstead – trivial trivium, the pub was literally started in a London pub – it became an iconic style bible for iconoclasts: those unmalleable Plastic People that didn’t fit society’s mould.

Dry, sarcastic and sardonic, its acidic voice was matched with base aesthetics and out-of-the-box box-outs. A cut-out ‘Lavatorial Security Aid’ in the first issue – ready to attach to a cubicle lock and let you “sniff away like a horny mongrel” – set the tone. Once reaching tens-of-thousands of readers, by 2003 it had folded, a victim of print media’s decline.

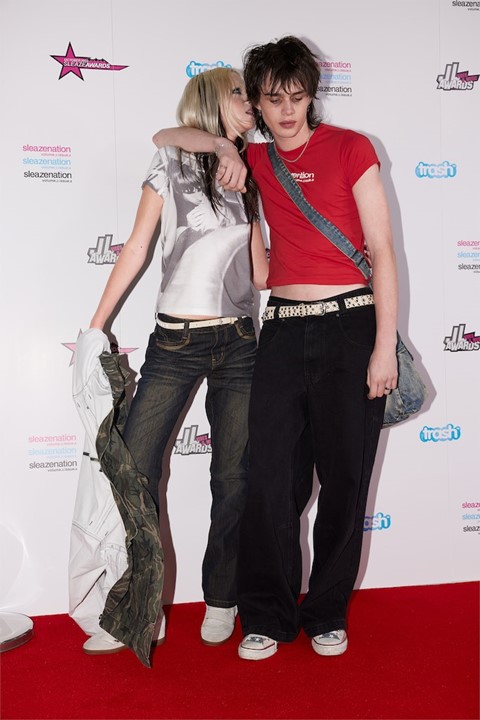

Now, Sleaze is back to make friends. Jaded London – which got some love in our style census – has just launched a new collection celebrating the zine’s most eyeball-pleasuring imagery. It features tees typeset with the Sleaze logo, sweats with cool kids pashing off in Pacha, literally cheeky hot pants emblazoned with “FUCKIN TUNE” and a pillow case for late night post-rave chats. The campaign sees scene kids shot in front of a fake awards show red carpet, poutily sucking on lollipops.

It’s made possible thanks to the Museum of Youth Culture, London’s archive of subcultural objects. “It’s the first time there’s been a museum dedicated to that teenage period of growing up,” says Jamie Brett, the head archivist. Founded by Swinstead, it holds the rights to the full slew of Sleaze imagery. “It’s untapped material that’s sitting in the vaults. We thought of perhaps launching an independent project or a book,” he explains.

Instead, Jaded got in touch, which is no wonder, since Sleaze has never felt more relevant. We are, after all, living in Sleazenation: The Sequel right now. “Jon said when they set the magazine up and were thinking of a name, the newspaper were saying “Tory Sleaze” plus there was quite a lot to take the piss out of as well,” Brett says.

Indie Sleaze has also given the word a new lease of life. “People are harking back to that irreverence and carefree, Cool Britannia attitude because times are so complicated at the moment,” says Brett.

Hear more from Brett below, talking about scene culture, Edwardian fashion, and trying to archive TikTok, and scroll through the Jaded London collection in the gallery above.

“People are harking back to that irreverence and carefree, Cool Britannia attitude because times are so complicated at the moment” – Jamie Brett

Hey Jamie! First of all, Why were Jaded and Sleazenation such a good fit?

Jamie Brett: I think what Jaded did is take us to somewhere that feels very powdery and glossy and a little bit trashy in a good way, all coming together for something that feels a really good fit. It’s very youth culture oriented.

I love that you chose to make most of the images full bleed. Why?

Jamie Brett: It’s full-on attitude. It’s about showing off your colours with pride basically. We’ve always said sometimes smaller images work quite well, if you have an exhibition, or it’s a really great rave image or whatever. But having it full-bleed is cool because it’s quite a technical thing to do as well. It requires a great supply network of people that know how to print. We’re really grateful to celebrate the archive in huge format.

It’s nice representing that contrast between print media and graphic prints…

Jamie Brett: Definitely, it’s been really interesting reaching out to photographers that have shot those images that we haven’t necessarily spoken to as much over the last few years. It meant we could reconnect with them. And they were all really excited to see their images, some they had forgotten about, being used. It’s interesting seeing that Sleazenation community that’s still going.

Is there anything about print media that’s not still going that you miss?

James Brett: There’s certainly a place for magazines, but I feel like they’ve become more of a voyeuristic sort of approach to what’s going on. It feels like they have become adjacent. That subculture of going to that local shop and picking up a mag or the record shop and clothes shop on the same road, or they’re in a certain area, that sort of gone and I think magazine is really integral part of that, as they connected them: where you go out at night, where you buy your clothes, and where you listen to music.

And there was that real mischievous rivalry, too.

Jamie Brett: There was a famous cover of Sleazenation which said “I’M WITH STUPID” and that pointed at magazines like i-D [on the shelves]. There were billboards that were bought above magazine offices making statements about them. I think there were magazines frozen in ice that were left outside of agencies and that, so they couldn’t open the door until it melted.

So yeah, there was a real playfulness about it. I mean, it’s something that we tried to continue with what we do at the museum. We still try to keep ourselves quite loose and entertaining. No one really wants to see a museum that just looks at youth culture as a thing of the past, it needs to be something that you use to inspire the next thing.

“It’s easy to be like, ‘there’s nothing and look how amazing these past scenes were’. But there’s so much digital innovation going on and people are expressing themselves emotionally and identity is becoming so much more nuanced. And I think that’s starting to create quite beautiful pockets of interconnected people” – Jamie Brett

In terms of the past, though, what do you miss about youth culture?

Jamie Brett: There’s so much. For me, Teddy boys were the pinnacle of style, there was a queerness to it since everybody was in double denim with a big heavy jacket over the top. The rave scene also has a nostalgic feel, you can always picture yourself in those hedonistic clubs and spaces and it was about painting a picture of the future. We’ve been thinking about emos recently.

Us too!

Jamie Brett: It ties in with lots of the Jaded style. We don’t have a huge amount of content at the museum from the emo and indie scenes. Back then, we still had to go to record shops and buy clothes from certain shops. It was trashy and it didn’t give a shit. We still have that attitude. But we’re losing the location, because it’s all moved online.

So are the kids alright?

Jamie Brett: It’s easy to be like, there’s nothing and look how amazing these past scenes were. But there’s so much digital innovation going on and people are expressing themselves emotionally and identity is becoming so much more nuanced. And I think that’s starting to create quite beautiful pockets of interconnected people.

How is the Museum of Youth Culture going to represent this in the future?

Jamie Brett: There are still going to be parties shot on film, plus digital stuff as well. With oral histories, you’ve always got a story in your head that you can tell, that hasn’t changed as a medium. It still has the same effect as someone talking about the 1950s.

The hardest thing is going to be how we index and catalogue the complexity of social media and things like TikTok. That’s not just a Museum of Youth Culture problem. I think it’s a Museum Everywhere problem. There are projects in Germany where there’s been like archiving social media stuff, and it’s mad. It takes teams of people staring at screens, trying to make sense of everything in context.

I remember reading about Mark Fisher’s thoughts on nostalgia and how it’s counterproductive to creating new subcultures. Is our revivalism part of this?

Jamie Brett: We’re always going to be looking at the past as nostalgia has a wide appeal. What’s interesting is that when I was a teenager, 20 years in the past was the 80s and that [seemed so outdated that it] felt like the 60s. Now we’re looking at the 2000s, which feels strange as it doesn’t feel very different to now.

We get sucked into something that never even happened. We weren’t even born. But we still feel it and we believe that it happened and then we embody it in some way. And sometimes that ended up being attended to a new subculture; like New Romantics dressing like Edwardians. But there’s a sort of a hauntology about subcultures, which is quite beautiful, really.