This summer, every day seems to bring another headline of tourists around the world behaving badly.

Last week, it was two drunk Americans sneaking into a closed section of the Eiffel Tower and sleeping off their bender high above Paris. The previous week, a French woman was arrested for carving a heart and her initials into Italy’s iconic Leaning Tower of Pisa. A Canadian teen defaced a 1,200-year-old Japanese temple last month, just after a Bristol-based man etched two names into Rome’s Colosseum and told authorities he was unaware of the arena’s age. And who could forget the German tourist who crashed a performance inside a sacred Bali temple and stripped naked – after having previously run out on the bill at several local hotels?

It feels like the whole world has forgotten how to act in other people’s homes. But while this may seem like the summer of bad tourists, it could just represent a rather uncomfortable truth: as long as people have travelled, we’ve misbehaved.

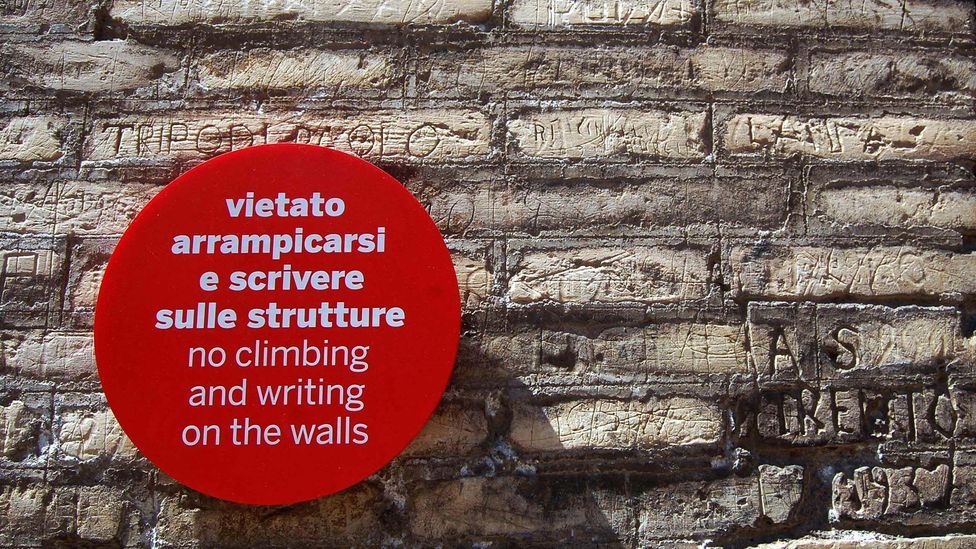

Signs at many of Italy’s famous monuments now beg tourists to not deface them (Credit: mark mcconkey/Alamy)

From Pompeii to the Egyptian pyramids, some of the world’s most famous man-made wonders are scarred with millennia-old graffiti etched into their walls by ancient sightseers. It’s no secret that many of the world’s “greatest” travellers – like Christopher Columbus and Hernan Cortes – were among its worst. And according to Lauren A Siegel, a tourism and events lecturer at the University of Greenwich in London, as recently as the 18th and 19th Centuries, it was common for British nobles taking the Grand Tour of Europe to belittle and disregard the people and places they were visiting.

What’s different about this summer is we’re increasingly hearing about bad travellers – and ultimately, this could be a good thing. With each new report of cringeworthy, tone-deaf or just plain disrespectful behaviour, our collective outrage seems to be rising, leading to what could just be a moment of reckoning for bad tourists.

In an age of heightened awareness about privilege and how we treat others from different cultures, this increased focus on entitled and boorish travellers may seem like a natural progression from other recent social movements. But experts suggest a combination of factors are driving bad behaviour abroad, and the newfound attention we’re giving it.

According to Siegel, unlike in years past, many travellers today are competing for social media likes and views. “People are reverting to more extreme actions for their Instagram or TikTok feeds,” she noted. Ironically, social media accounts like the massively popular Passenger Shaming are also being used to call out insensitive and disrespectful behaviour.

Accounts on social media are increasingly documenting bone-headed traveller behaviour (Credit: Imaginechina Limited/Alamy)

David Beirman, an adjunct fellow at the University of Technology Sydney, noted that nearly 1.5 billion people travelled internationally in 2019. With travel now surging to its highest levels since before the pandemic, he said it’s inevitable some tourists will think “it’s cool to pose nude in front of a temple in Bali, get drunk at an Islamic holy site or dance in front of a Nazi concentration camp”.

Gail Saltz, host of the How Can I Help? podcast, said she sees other factors at play too, including “revenge travel” following years of pandemic lockdowns and anxiety. “People have this feeling that it’s only fair that I now get to do things that I didn’t get to do [during lockdown], and I get to do them in spades,” she said. “They come with a mindset that [foreign countries are] a great big party and I get to do what I want.

In particular, Saltz isn’t surprised by the number of people caught engraving their names on ancient monuments. “They think this is a chance to immortalise themselves.”

Yet, this summer’s shameful headlines may offer an opportunity for change. With each new offense, we’re reminded that international travel is a privilege.

It’s not uncommon to see travellers posing for selfies at Berlin’s Holocaust memorial (Credit: Nacho Calonge/Alamy)

Nowhere has this inherent truth been more evident recently than in Hawaii. As the deadliest wildfires in modern US history tore through parts of Maui (one of the most popular tourism destinations in the US), thousands of beach-seekers have continued to fly in, with one local telling the BBC that tourists were swimming in the “same waters that our people died in three days ago”.

Privilege brings responsibility, and one can only hope that, just as we may recoil at a #passengershaming image of a traveller whose bare feet is resting on another’s head, we learn to collectively shudder at the thought of travellers complaining they can no longer go ziplining in Lahaina amid a natural disaster.

The beautiful thing about travel is the world’s wonders become even more wonderful after you visit them yourself. We care more deeply about what we know and are more prone to help protect it – or at least not destroy it.

The recent film Oppenheimer acutely makes the point. In a memorable scene, US Secretary of War Henry Stimson pointedly removes Kyoto from the list of cities targeted for the atomic bomb. The ancient Japanese capital, with its temples and monasteries, was too precious to destroy. He knew this, he said, because he had honeymooned there. In the movie, it’s a laugh line, but the message is real. We don’t harm what we hold dear.

Kyoto was saved by a potential atomic bomb blast because the US Secretary of War had honeymooned there (Credit: RichLegg/Getty Images)

Several destinations have taken a proactive approach to this idea. Tourism hotspots like Bali and Iceland now formally ask tourists to promise to respect their culture and environment after visiting it. Palau requires visitors to sign an eco-pledge on arrival. Bucket-list locations are also increasingly regulating tourists. Visitors to Australia can no longer climb Uluru (Ayres Rock), because the country recognises it as an Aboriginal sacred site. Meanwhile, Amsterdam recently launched a “stay-away” ad campaign targeting drunk Brits.

Siegel applauds these stricter guidelines, and what she sees as a growing recognition of the problem by fellow travellers.

She points to a new “Instagram vs Reality” trend in social media, where people purposely show the behind-the-scenes crowds and chaos common at tourism hotspots often omitted from influencers’ perfectly composed images and videos.

Amsterdam has been actively trying to discourage drunk Brits from visiting (Credit: Roger Coulam/Alamy)

And each time that happens, our global treasures will be a little safer.

Larry Bleiberg is past president of the Society of American Travel Writers.

—

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.