It was the middle of the night when the phone call came.

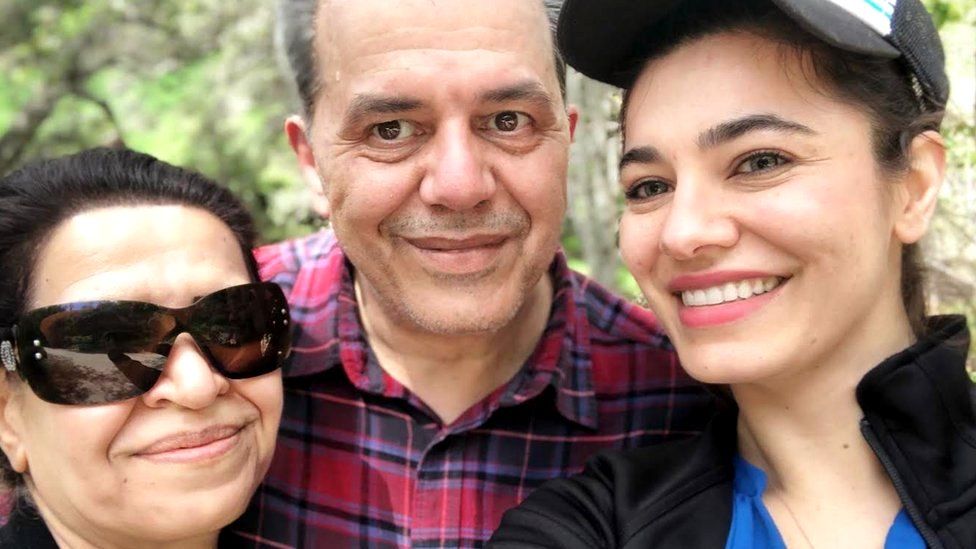

Gazelle Sharmahd was woken up by her mother, who told her that her father, Jamshid, was calling from his jail cell in Iran. Gazelle hadn’t been allowed to talk to her father, an Iranian-German businessman, for two years.

“We didn’t even know if he’d already been executed and they hadn’t told us,” she told me from her home in Los Angeles a few days later.

Iran sentenced Jamshid Sharmahd to death last February for so-called “corruption on Earth” – a vague catch-all term the Iranian regime uses for any expression of opposition. Amnesty International condemned his trial as a sham.

His daughter was overjoyed to talk to her dad again, but she is tormented by the fear that this phone call was allowed in order for her to say goodbye before his execution.

For almost three years the 68-year-old has been in solitary confinement in an Iranian jail, cut off from the world. During the one-hour phone conversation his daughter suddenly realised he hadn’t even been told about his death sentence.

Earlier this month Gazelle Sharmahd launched a criminal complaint here in Germany, calling on German state prosecutors to investigate eight high-ranking members of the Iranian judiciary and intelligence service for crimes against humanity, because of the way her father has been treated.

Her father has lost his teeth – either through malnutrition or violence – so he can’t eat. He can’t walk or talk properly because he suffers from Parkinson’s and is not being given his correct medication.

“They’re killing him softly in solitary confinement in this death cell. But even if he survives that, they’re killing him by hanging him from a crane in public,” she said. “They want a public execution for my dad, to send out this message of terror: that anybody who speaks out against the regime, we can do this to you – look at this person that’s hanging there.”

Jamshid Sharmahd was born in Iran, grew up in Germany and has dual nationality. He worked as an engineer for Siemens before setting up his own tech business in the US in the early 2000s.

It was only when he became the target of an Iranian hacking attack that he started publicly voicing his opposition to the Iranian government.

Then, three years ago, while on a layover in Dubai during a business trip, he was abducted and taken to an Iranian jail. The list of accusations became endless, from spying for the Americans, the British and the Germans to numerous supposed terror attacks. German and EU politicians say the charges are bogus.

“Even in Iran, you can’t sentence someone for terrorism without proof,” said Gazelle Sharmahd, which is why the death sentence is for “corruption on Earth”.

Gazelle, who grew up in Germany and is now an intensive care nurse in the US, has long campaigned for her father’s release, but says she got little support from the German government.

That is why she launched her criminal complaint, using the principal of universal jurisdiction to target senior officials in Iran’s judiciary and intelligence. This enables crimes against humanity or war crimes to be prosecuted anywhere in the world, regardless of where the crimes were committed.

Gazelle Sharmahd’s German lawyer, Patrick Kroker of the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, used this principle last year to prosecute a former official of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad for torture and murder committed in Syria. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in Germany.

Mr Kroker believes such cases can act as a deterrent and prevent human right abuses because perpetrators can’t be sure they won’t be arrested as soon as they travel.

“High-level government officials are used to having a lifestyle that enables them to visit the niece who’s studying in Paris, or go skiing in Sweden. And this is not possible any more – at least they cannot be secure of that,” he said.

But it’s not clear how the Iranian authorities will respond and Gazelle Sharmahd still fears that her father could be executed at any minute.

Germany has the largest Iranian diaspora in Europe. But Iranian-Germans tell me they feel ignored by the German government.

At a protest at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, I met Alina, an Iranian-German, who was impressed by Gazelle Sharmahd’s dedication to free her father. “It brings tears to my eyes and I get goosebumps when I think of how Gazelle is fighting for her dad,” Alina said.

Like many people I spoke to, she didn’t want her full name or photograph to be publicised because of fears that she, or her family, will be targeted by Iran.

But she was outraged by what she regarded as a lack of political support for Jamshid Sharmahd – and that has left her feeling vulnerable too.

Despite being a German citizen, Alina believes that if the same thing happened to her, or anyone in her family, the German government would not help.

“I know my country doesn’t have my back. I’m alone.”

Some Iranian-Germans suspect racism, asking whether Mr Sharmahd is not seen as a “real” German citizen, despite having grown up here. Others accuse Berlin of prioritising trade over human rights.

I put those allegations to the German Foreign Office, which replied that Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock had repeatedly stated that the death sentence was “absolutely unacceptable”.

“The German government sees the death sentence as a massive violation of the rights of a German citizen,” the statement said.

It also pointed out that Iran views Mr Sharmahd exclusively as an Iranian citizen, and refuses Germany diplomatic access.

“We continue to advocate for Mr Sharmahd with the utmost effort – at a high level, through all available channels and at every opportunity. Carrying out the death sentence would have serious consequences.”

But the Iranian-German community remains frustrated.

Many feel threatened and persecuted by Iran. But not necessarily protected by Germany either. Just forgotten.

Related Topics

- Germany

- Iran

- Capital punishment