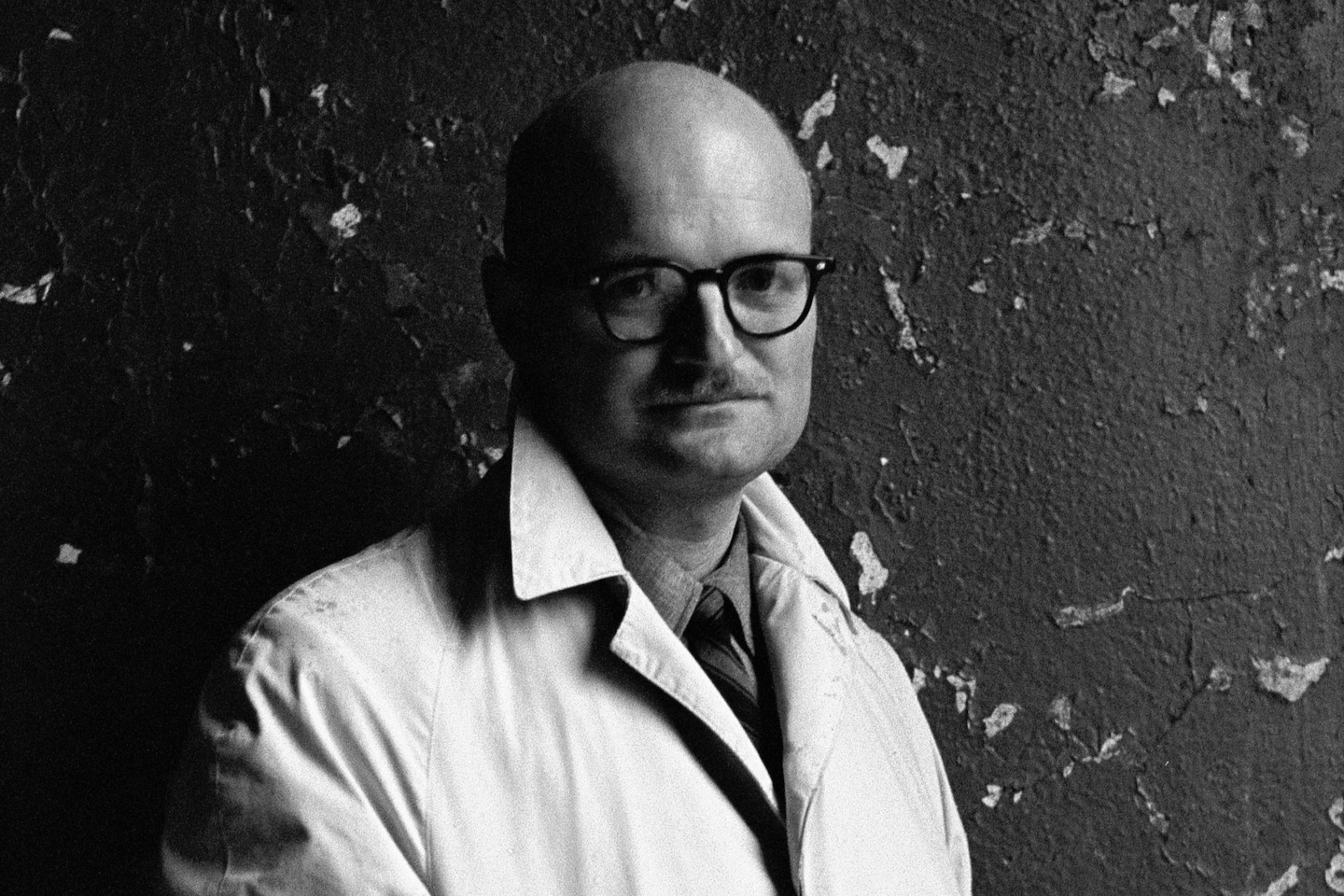

John Barth, a novelist who crafted labyrinthine, fantastical tales that were at once bawdy and philosophical, placing him on the cutting edge of the postmodern literary movement, died April 2. He was 93.

His death was announced in a statement by Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he was a longtime faculty member. The statement did not say where or how he died.

Mr. Barth was the author of about 20 books, among them the short-story collection “Lost in the Funhouse” (1968), a landmark of experimental fiction, and the comic novels “The Sot-Weed Factor” (1960) and “Giles Goat-Boy” (1966).

The former was included on Time magazine’s 2010 list of the 100 greatest English-language novels, and in 1973 Mr. Barth won a National Book Award for “Chimera,” a collection of three interrelated novellas that retold the mythical stories of Perseus, Bellerophon and Scheherazade. (Mr. Barth, not for the last time, appeared as a character in the work, making a cameo as a smiling genie who offers Scheherazade, or “Sherry,” fresh material for the stories she tells each night.)

Despite such acclaim, Mr. Barth’s books were sometimes criticized by peers as academic, pretentious and willfully obtuse. Where novelist John Updike offered praise, favorably comparing the marital dramas of “Chimera” to his own work about domestic discontent, writer Gore Vidal offered a scathing assessment: Mr. Barth’s books, he said, were “written to be taught, not to be read.”

Mr. Barth was, in fact, for many years a professor, teaching English and creative writing at his alma mater, Johns Hopkins. While he saw himself as a teacher as much as an author, he believed he was writing squarely in the tradition of storytellers such as Homer, Virgil and the imprisoned character of Scheherazade, whose storytelling prowess led her captor to spare her life.

He was, he said, a kind of literary arranger, enacting in literature what he had briefly done in his youth as an orchestrator for a jazz band.

“An arranger is a chap who takes someone else’s melody and turns it to his purpose,” Mr. Barth told the Paris Review in 1985. “For better or worse, my career as a novelist has been that of an arranger. My imagination is most at ease with an old literary convention like the epistolary novel, or a classical myth — received melody lines, so to speak, which I then reorchestrate to my purpose.”

Mr. Barth’s “reorchestrations” made him one of the foremost practitioners of postmodern literature, a movement that he helped define as the blending of straightforward storytelling techniques with the involuted, playful, frequently self-referential devices of modernists such as James Joyce and Samuel Beckett.

He was perhaps at his postmodern best — or worst, depending on one’s tastes — in “Lost in the Funhouse,” the title piece of his first story collection and a formative influence on the late David Foster Wallace.

The story shifts seamlessly between a traditional narrative — about a young boy’s trip to a hall of mirrors, located at a beach resort near Mr. Barth’s hometown on the Eastern Shore of Maryland — and observations on the nature of narrative itself.

A story, Mr. Barth seemed to suggest, was itself a kind of funhouse, one in which readers are made to believe that they are experiencing something real and true, rather than an artifice constructed out of words on a page.

“So far there’s been no real dialogue, very little sensory detail, and nothing in the way of a theme,” the story’s narrator observes early in the piece. “And a long time has gone by already without anything happening; it makes a person wonder. We haven’t even reached Ocean City yet: we will never get out of the funhouse.”

John Simmons Barth, whose father owned a candy store, was born in Cambridge, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, on May 27, 1930. He went by Jack, complementing his twin sister, Jill.

Mr. Barth played the drums in a local jazz group and briefly studied orchestration at Juilliard music school in New York before transferring to Johns Hopkins.

“As an illiterate undergraduate,” he once told the New York Herald Tribune, “I worked off part of my tuition filing books in the Classics Library at Johns Hopkins, which included the stacks of the Oriental Seminary. One was permitted to get lost for hours in that splendiferous labyrinth and intoxicate, engorge oneself with story.”

His interest was in narrative: sprawling epics such as “The Ocean of the Rivers of Story,” a multivolume work originally written in Sanskrit; Giovanni Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”; and Richard Burton’s translation of “The Thousand Nights and a Night,” which taught him how to pace epics and led to a fascination with stories within stories.

After graduating from Johns Hopkins with a bachelor’s degree in 1951 and a master’s in English in 1952, he planned a trilogy of short realist novels to address themes of suicide and nihilism.

The first two volumes — “The Floating Opera” (1956) and “The End of the Road” (1958) — were well-received but left Mr. Barth feeling unsatisfied. While teaching at Penn State, he later told The Washington Post, “I realized that realism was tying my hands.”

He responded by ditching plans for his third novel and — finding the playful, parodic voice that dominated most of his later work — launching himself to literature’s experimental fringe.

The result was “The Sot-Weed Factor,” a darkly funny, 800-page satire of Colonial Maryland that drew inspiration from a 1708 poem of the same name. In Mr. Barth’s telling, the poem’s author — a “rangy, gangling flitch called Ebenezer Cooke” — was a naive idealist grappling with the growing awareness that human existence is grim, fraught with violence and lacking in apparent purpose and meaning.

Written in the style of picaresque novels such as Henry Fielding’s “Tom Jones” and Laurence Sterne’s “Tristram Shandy,” the novel was “not for all palates,” the novelist and critic Edmund Fuller wrote in a review for the New York Times: “The plot itself is a parody in its incalculable complexity; a tissue of intrigue and counter-intrigue, ludicrous mock-heroic adventure, masquerades and confusions of identity.”

Mr. Barth’s follow-up, “Giles Goat-Boy,” was nearly as lengthy and even more outlandish. The book, its author once explained, was “a farcical allegory . . . of a goat sired by a virginal librarian on a computer.”

Improbably, it landed on the Times bestseller list for 12 weeks, helped along by praise from literary critics such as Robert Scholes, who hailed Mr. Barth as “a comic genius of the highest order” in a front-page review in the Times Book Review.

Mr. Barth continued his hyper-intellectual strain of writing in “Letters” (1979), a parody of epistolary novels that featured imagined correspondence between Mr. Barth and characters of his previous works, before turning to a more straightforward style in “Sabbatical” (1982).

The book was Mr. Barth’s most openly political work, and included about 20 pages of news clippings from the Baltimore Sun about John Paisley, a former CIA official whose body was discovered in the Chesapeake Bay in 1978, spawning conspiracy theories that he was silenced by the intelligence agency.

It also seemed to include elements of autobiography. Its protagonists were a husband and wife who, like Mr. Barth and his own wife, the former Shelly Rosenberg, sailed across the Chesapeake. (Mr. Barth, the owner of a 25-foot fiberglass sailboat, once told The Post that “one of the purposes of art is to give you boats you can’t afford.”)

A previous marriage, to Harriet Anne Strickland, ended in divorce. He had children, but information on survivors was not immediately available.

Mr. Barth received some of the most glowing reviews of his career for “The Tidewater Tales” (1987), a sequel of sorts to “Sabbatical.” The novel featured another husband and wife, this time with a male protagonist who appeared to be Mr. Barth’s literary opposite: a minimalist author who finds Shakespeare’s remark “Brevity is the soul of wit” to be “five-sixths too garrulous.”

The book, like his earlier work “Chimera,” featured a cameo from the mythical Scheherazade, whom Mr. Barth described as his “literary patron saint.”

“We like to imagine that our lives make sense, and storytelling is one way of ordering events,” he told the Times in 1982. “Of course, Scheherazade literally has to keep telling stories or she’s kaput. In a less dramatic way, that’s true of every writer in the world — you’re only as good as your next story.”