José María Velasco was born in the village of San Miguel Temascalcingo in 1840; he lived through three Mexican republics, an empire, a dictatorship, a civil war, the invasion of his country by America and then by France and, in his last two years, 1910-12, a revolution.

When Mexico failed to resist American forces in 1847, Mexican jurist Mariano Otero lamented: “Mexico did not constitute, nor could it properly call itself, a nation.” Velasco helped the country see itself. Studying geology, zoology, botany and art, he combined them in his life’s work: paintings monumentalising Mexico’s unique topography, flora and fauna. His majestic landscapes “The Valley of Mexico” became his troubled young nation’s visual emblem.

Treasured at home and rarely loaned, 14 canvases plus a handful of works on paper arrive in London from Mexico for the National Gallery’s José María Velasco: A View of Mexico — its first ever show devoted to a Latin American artist. From Prague come another three, acquired by Czech pharmacist Frantisek Kaska, who accompanied Habsburg Emperor Maximilian’s ill-fated campaign in Mexico and survived. (Maximilian was executed in 1867; Manet’s painting imagining the event hangs in room 41.)

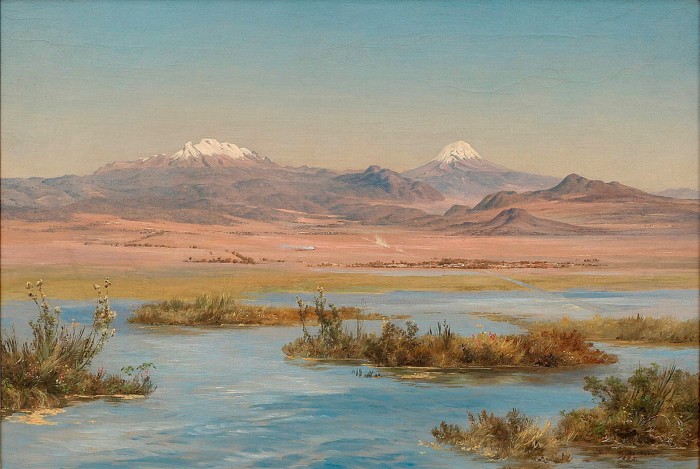

Kaska commissioned the luminous floating panorama “Lake Chalco” (1885) which opens the show and typifies Velasco’s strange fusion of European-derived academicism, scientific enquiry and Mexican lore and landscape. Chalco sustained rich plant and wildlife — Velasco wrote an essay on its salamanders — but it was about to be drained; the painting would be its picturesque memorial. Velasco places the viewer at water level, waves lapping lush vegetation, meticulously rendered leaf by leaf. But we gaze up at two snow-capped peaks, the volcanic cone Popocatépetl and the humpbacked Iztaccíhuatl. More than mountains, they are legendary characters in a pre-Hispanic tragic love story between an Aztec princess (Iztaccíhuatl, “white woman”) and a brave fighter (Popocatépetl, “smoking mountain”).

Velasco unites 19th-century romanticism, ancient romantic myth, and eco-warrior warning of destruction amid industrial expansion. Plumes of smoke unfurl from a train traversing the plain — change set against the peaks’ eternal presence. The painting’s precise lyricism displays the influence of Velasco’s teacher Eugenio Landesio, an Italian romantic painter who arrived in Mexico in 1855, but Velasco is a fiercer realist, thrilling to the force of nature, and also insistent on including contemporary motifs. These qualities made him the man for Mexico’s nationalist moment, and he brings a refreshing tropical mood to the European bastion of the National Gallery.

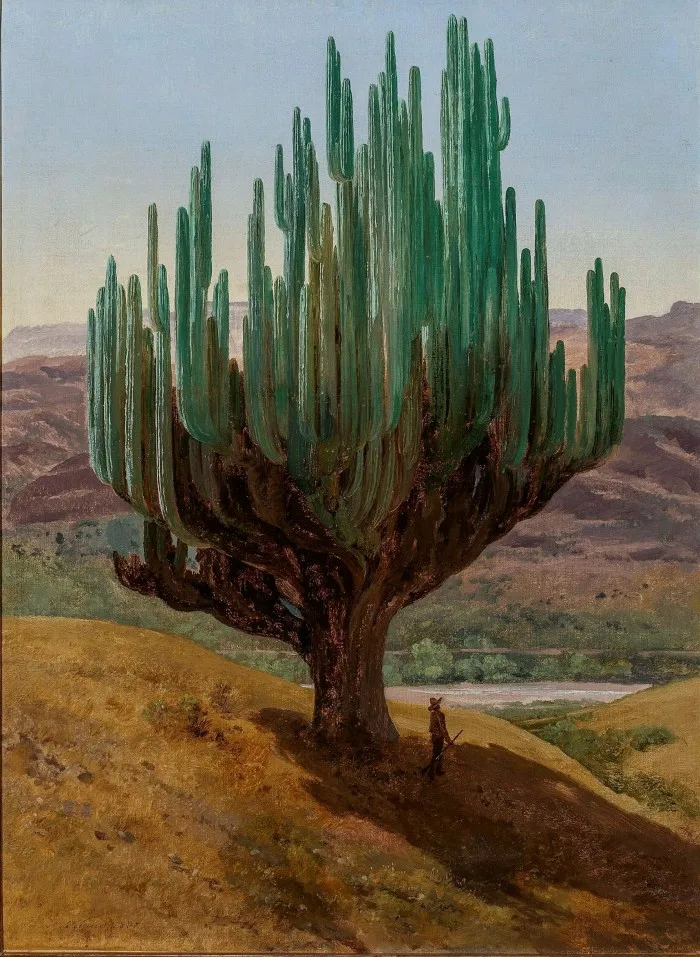

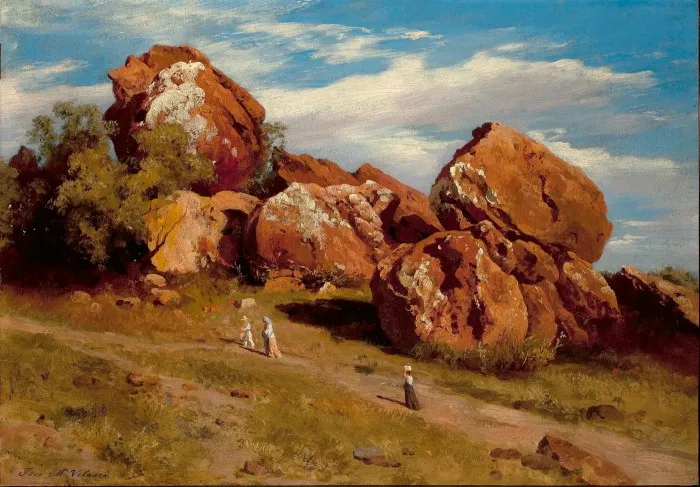

“The Forest of Pacho” (1875) plunges you into the jungle, the thick skein of ferns in variegated greens stifling in its horizonless splendour. The giant sculptural cactus “Cardón, State of Oaxaca” (1887), its spikes dwarfing hills and rivers, and the sharply delineated “The Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacán” (1878) in faltering evening light have a surrealist enchantment, prefiguring lo real maravilloso, the marvellous real, that Cuban Alejo Carpentier thought distinctive to Latin American art. In “Rocks” (1894), the intricate surface of a purple outcrop on the hill of Tepeyac confronts us like a severe portrait face.

But Velasco can be mystical too: in “The Great Comet of 1882”, its white tail reflected on a silvery lake dissolving into shadow, distant Mexico City becomes a mere grid of tiny lights, trembling awake at dawn to the blue-grey gradations of a huge sky. This was painted during political unrest in 1910, the comet a metaphor for the coming revolution and instability. It shows Velasco’s alertness to his times even in old age.

For, although little known outside Mexico, Velasco’s art is not an isolated phenomenon; he is an intriguing chapter in a story ranging across 19th-century Europe and the Americas: landscape’s triumph over history painting as the genre defining culture and nationhood.

The two vast bird’s-eye vistas “The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel” unfold distinctive Mexican life over centuries. In the 1875 version, our eye follows the Sierra de Guadalupe Mountains to the town Villa de Guadalupe. Here in 1531 Juan Diego, an indigenous convert, saw a vision of the Virgin of Guadalupe, who became a major Mexican cultural icon — not coincidentally, the area was associated with pre-Hispanic female deities.

In the distance, Velasco delineates the causeway connecting the shore to the Mexica city Tenochtitlan, founded in 1325 in the middle of lake Texcoco and the forerunner of Mexico City; the route was repurposed as the Spanish Calzada de los Misterios, dotted with baroque monuments to the mystery of the rosary. A woman carrying a basket of prickly pears represents indigenous communities. This painting travelled to the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia marking American independence; it symbolised Mexico’s.

A year later, amid fears of invasion when American troops massed at the border, Velasco painted a more austere, epic representation of the expansive valley cradling Mexico City. The mountains again surge, but instead of human figures, an eagle carrying a bird swoops towards a prickly pear plant; according to Aztec prophecy, a bird of prey alighting on a cactus would determine the site of Tenochtitlan. Velasco recasts ancient symbols as romantic realism, emphasising the painting’s present tense: he wrote that “the effect of the light in the picture is from one of the first days of June at three o’clock in the afternoon.”

Velasco revisited the motif for decades, always faithful to observed reality yet subtly reimagining space to blend imagery of the natural and man-made world into ample harmonies. The crystalline “Valley of Mexico from the Molino del Rey” (1895) features the castle where six young naval cadets sacrificed their lives in the 1847 Battle of Chapultepec against America; a colonial-era mill; an agave plant, used to make tequila, asserting tradition; and a smoking chimney demonstrating encroaching industrialisation.

Velasco could be more emphatically modern than this; it is unfortunate that his most audacious painting, the train rushing towards the viewer as it crosses “The Curved Bridge of the Mexican Railway over the Metlac Ravine” (1881) hasn’t travelled. On the evidence here, he seems in European context a throwback, oblivious to the painterly transformations of his contemporaries the French impressionists, sharing rather an aesthetic with earlier academic romantics such as Germany’s Caspar David Friedrich and Norway’s Johan Christian Dahl (both displayed in room 39). The similarities reinforce how romanticism and nationalism marched hand in hand through the 18th and 19th centuries, especially in nations coming into being.

When the show moves to Minneapolis in September, however, the conversation will be with Velasco’s direct American peers Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran, romancers of the wild west: a contrast between the American sublime, idealising a wilderness ripe for conquest, with scant reference to its Amerindian past, and the layers of history and geography with which Velasco skilfully celebrated Mexico’s resilient mixed identity.

National Gallery, London, March 29-August 17, nationalgallery.org.uk; Minneapolis Institute of Art, September 27-January 4 2026, new.artsmia.org