Michigan Supreme Court Justice Richard Bernstein wants to keep his seat on the high court until he’s kicked off at age 70. But to do it, he needed to leave the bench and treat his depression.

Bernstein, who already broke one barrier by becoming the first blind person to ascend to the Michigan Supreme Court, publicly announced in April that he’d temporarily leave the bench to seek out-of-state mental health treatment. This unprecedented action was a breakthrough, experts told Bloomberg Law.

LISTEN: Reporter Alex Ebert discusses this story on our weekly On The Merits podcast

“I didn’t like that I didn’t have the love or the excitement or the energy or the enthusiasm for life that I had,” Bernstein told Bloomberg Law. “I’m not going to live without loving life.”

Click the Listen button to hear an audio version of this story.

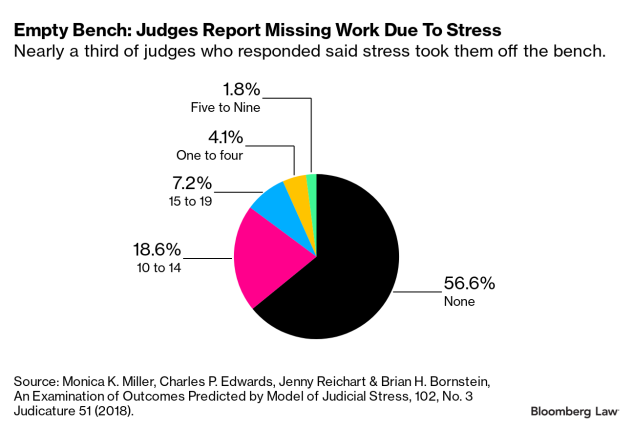

Bernstein is opening up about his struggles in the hope that his example will make it easier for other judges to seek help. Under the black robes are people facing perpetual stress, long work hours, and exposure to human tragedy. Surveys indicate roughly a quarter of judges missed at least 10 work days in the last year due to stress—though they gave other reasons to their bosses—and nearly 50% of judges believe they’ve suffered secondary traumatic stress from exposure to heartbreaking court testimony and gruesome photographic evidence.

However, fear of damaged reputations and voters’ rebukes lead judges to struggle in silence, with the public paying the price, experts say.

Michigan alone has roughly 550 trial court judges. If a quarter miss 10 days due to mental health struggles as research suggests, that’s the equivalent of 1,375 days, or 11,000 hours, reducing the efficiency of dockets and courts’ ability to work through backlogs generated during the pandemic.

“The suppressing of help-seeking behavior is so consistent across the legal system,” said Bree Buchanan, an internationally renowned judicial wellbeing researcher and advocate, “because reputation is all.”

Buchanan worked a national treatment hotline for judges. She said it was like being the lonely Maytag repairman, sitting by a phone that rarely rang. And while states are working to expand and publicize confidential mental health programs for judges, lawyers, and law students, those programs will continue to be under-utilized unless others like Bernstein step forward.

“There’s a lot of fear among leaders to take this topic up because it can potentially cast a dark shadow over the judiciary,” she said. “What Bernstein did is profoundly helpful in breaking down the stigma.”

‘Almost Unlimited’

Bernstein’s days are full of long hours in chambers, long miles on treadmills, and long flights to international summits. His life’s work is to improve the world for disabled people through the legal system—having notched wins as a lawyer with football stadium accommodations, wheelchair public transit accessibility, and revamped airline policies.

“When you live with that sense of purpose, sense of mission, and sense of passion it really does drive you,” he said. Then depression “robbed him of his joy.”

Without treatment, Bernstein knew he couldn’t find joy in the work.

After a month working remotely during his treatment, Bernstein was back to early workouts and late courtroom hours. He starts by running several miles on a treadmill, training for his next marathon. He’s completed 26, as well as an Ironman Triathlon, with the help of guides. Then he’ll get a ride to court, where 12-hour days are the norm, filled with writing and memorization work with his clerks.

When court isn’t in session, Bernstein travels the country and the globe with the US State Department, giving speeches and advocating for those with disabilities on the international stage.

“We usually work six days a week, seven days if there’s oral argument. It’s like a conveyor belt. The work just keeps on coming; you have to keep running as fast as you can to keep up with it,” he said.

For Bernstein, there another added level of difficulty—he was born with retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited eye disorder. Bernstein, now 49, was blind from birth, meaning to prepare for oral arguments and meetings he has to memorize immense amounts of legal material because reference materials in Braille would fill up an entire court conference room.

“The amount of reading and writing that has to be done to discuss the pending cases with your colleagues is almost unlimited,” said Bridget McCormack, a former Michigan chief justice who worked with Bernstein for the better part of a decade.

“I never in 10 years on the court had a weekend off,” McCormack, the president and CEO of the American Arbitration Association, said. “I always needed evenings and the weekends to do just the reading and writing that had to be done to keep up with the job.”

‘A Blessing’

Bernstein said a trifecta of issues plagued him.

Chronic pain was the first headwind. He was struck by a cyclist in New York’s Central Park more than a decade ago, shattering his hip and pelvis. He emerged from a 10-week hospital stay with pain that’s never left.

The second was isolation during Covid-19. Bernstein, who relies on people, was prevented from being around them, which he said stole the “energy” he got from them. The third was some personal trauma, which Bernstein declined to discuss.

“It had really taken away the love, and the joy, and the enthusiasm I had for everything,” he said. “And I wanted to get that back, because it’s who I am.”

Lawyers, and especially judges, have unique stressors and needs, said Molly Ranns, a counselor, addiction clinician, and director of the State Bar of Michigan’s Lawyers & Judges Assistance Program. In presentations across the state and country, she addresses the pressure of the field—including compassion fatigue and isolation—and discusses how therapy can help.

“It really is a mirror for someone to look into and to see how they are in the world and what changes they want to make,” she said. The state’s confidential assistance program saw a 9% increase in 2022, and a record-high number of requests for confidential services. In its last fiscal year, the program has also had a 23% jump in presentations on these services for professional organizations.

Bernstein said after treatment he returned even better than before—his depression gone.

“It gives you a greater understanding and a greater appreciation of life,” he said. “And now, when people come before me, I have a greater sense of empathy, a greater sense of compassion, a greater sense of understanding. And maybe it is a blessing.”

‘Lose Your Name’

Bernstein’s transparency raises a new question in judicial politics: will voters care about a judge’s mental health treatment?

After a failed 2010 bid for state attorney general, Bernstein shifted his target to the state high court, winning election in 2014 and re-election in 2022. His dream is to hold onto his seat until forced retirement at 70. To do that he’ll have to win elections for the next two decades.

Public perception, Buchanan said, is the biggest hurdle for lawyers seeking treatment because they worry others will find out. Law students worry they’ll never get jobs; associates worry they’ll never make partner; partners worry they’ll lose clients; and judges worry voters won’t re-elect them. This can give lawyers—and especially judges—a feeling of isolation and a sense that they can’t confide in anyone.

“When you’re elected, you lose your first name. You’re no longer ‘John,’ you’re ‘judge,’” said Buchanan. “That can become a breeding ground for issues like depression, anxiety, and substance abuse trying to medicate these things.”

Yet research indicates modern judicial campaign messaging hinges mostly on the decisions judges have authored or policies they’re supporting, Southwestern Law School Professor Richard Jolly said. In politically purple Michigan, one of the highest-spending states for judicial elections, attacks on Bernstein’s treatment would likely backfire like attacks on Pennsylvania Sen. John Fetterman (D), who is recovering from a stroke and publicly took leave of Congress to receive mental health treatment.

“Our state Supreme Court elections are more politicized today than they were in decades passed, and maybe that means Justice Bernstein will face political attacks based on his treatment,” he said. “But attacking an unsighted person for seeking mental health treatment is not a good political tactic.”

Bernstein said his dealing with situational depression has made him a better judge and candidate.

“I bet I’m going to do better because people will connect. They’ll identify with how human you are.”