Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Popular Music

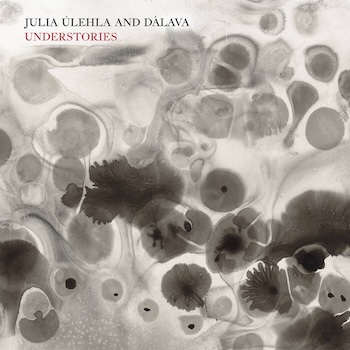

The weight of history looms behind Julia Úlehla and Dálava’s interpretations of traditional songs from the Czech region of Moravia. An American whose family originated in the Czech Republic, Úlehla is reaching back, with a modern sensibility, to the music that her great-grandfather grew up with. Understories (PI Recording) evokes roughhewn musical images of a desolate rural European landscape. The production’s uncanny sound design deploys reverb and loops.The band includes guitarist Aram Bajakian, who is Armenian-Canadian, Peggy Lee on cello, and Josh Zubot on violin.

Úlehla’s training in opera is audible. She works in the higher parts of her register. Dálava’s music carries the rural emotions of the past proudly, but those feelings tend towards the doom-laden. Their inclusion of drones and noise in folk music is hardly unprecedented: the Irish band Lankum are the most high-profile artists to work in similar territory. That said, Understories is a radically stripped-down example of the genre; Bajakian’s piercing chords echo off samples of creaky percussion.

“bowed low” ends with a menacing rumble of distorted guitar and scraped strings. “open your ear to the earth below” sets Úlehla’s voice atop volcanic blasts — with little other support. The vocalist sings opposite herself to great effect. In “escape velocity,” several incarnations of her voice overlap, jostling against each other. Overdubbing and reverb enhance her range and depth. In “the way up,” her voice is eloquent without words. Bajakian switches to violin for the arctic gloom of “entanglement.” “phase transition” dramatizes desperation.

Dálava can rock out, as its 2017 song “The Rocks Began to Crumble” proved, but Understories hews to the sound of counterculture wanderers such as Nico and Tim Buckley. Their current label, Pi Recordings, is associated with jazz, so this album is a departure for the company. But Understories exudes the same spirit of freedom as the label’s releases by Steve Lehman, Henry Threadgill, and Tyshawn Sorey, which are united by refusing the limits of genre and national boundaries.

— Steve Erickson

Matmos’ M.C. Schmidt and Drew Daniel. Photo: Obie Feldi

Each Matmos album has a simple concept. Most often, the Baltimore electronic duo construct their music from samples taken from one source: 2001’s A Chance to Cut Is a Chance to Cure drew on the sounds of surgery. Although Metallic Life Review (Thrill Jockey) incorporates live instruments, most of its sounds come from a variety of metal objects. Among other kinds of percussion, the group bowed and struck aluminum rods, pots and pans, cemetery gates, and aluminum cans.

Sampling allows Matmos to create imaginary instruments. (They also worked with live musicians on this album, including the late pedal steel guitarist Susan Alcorn.) This antic approach to sonic transformation is most effective on “The Rust Belt,” where noise that initially suggests a factory transforms into what sounds like an after-hours dance club. The duo concocted an enormous drum kit accumulating endless variations via hammers slamming on metal. The gleeful, childish melody of “Steel Tongues” turns a glockenspiel into a giant music box. “Changing States” inserts a slow, uncanny drone over lickety-split percussion and then introduces the album’s first melody. The track is also faintly Latin, its metal instrumentation warped into approximations of congas and maracas.

The pair are careful songwriters, creating music that ebbs and flows. There’s no lazy pasting of loops on top of one another. In other words, along with Matmos’s mischievous experimentation, the band has an ear for tunes and grooves. “Norway Doorway” references Pierre Henry’s composition “Variations on a Door and Sigh”: it kicks off with a gong, which is joined by a squeaking door. The latter is manipulated into a whining noise redolent of a squawking saxophone, while an anxiety-inducing soft pulse grows louder and louder.

The title indicates the album’s private meaning for the duo. It’s not apparent from listening to the album, but Matmos recorded it with sounds that they have heard throughout their lives. They even banged away on pots and pans dating from their childhoods. This is a clever conceit, but the record’s shifting textures reflect a depth that goes well beyond a witty idea.

— Steve Erickson

What Did The Blackbird Say To The Crow? (Nonesuch) is a spirited reunion of former Carolina Chocolate Drop members Rhiannon Giddens, on banjo, and Justin Robinson, on fiddle. The album is both a loving homage to the jigs and reels of the Carolina Piedmont and a celebration of Black roots music as a genre of folk unto itself.

As Giddens explained to Variety: “Justin came to me. He hadn’t been doing music for years, and then I saw him out playing again, and I was like, ‘Oh, come and let’s play these tunes we haven’t played in a while.’ I was just struck with how beautiful the thing that we do is, just fiddle/banjo. We were trained by a string-band musician connected to deep history [

What Did The Blackbird Say To The Crow? (Nonesuch Records) is a spirited reunion of former Carolina Chocolate Drop members Rhiannon Giddens, on banjo, and Justin Robinson, on fiddle. The album is both a loving homage to the jigs and reels of the Carolina Piedmont and a celebration of Black roots music as a genre of folk unto itself.

As Giddens explained to Variety: “Justin came to me. He hadn’t been doing music for years, and then I saw him out playing again, and I was like, ‘Oh, come and let’s play these tunes we haven’t played in a while.’ I was just struck with how beautiful the thing that we do is, just fiddle/banjo. We were trained by a string-band musician connected to deep history [the late Joe Thompson, the legendary North Carolina Piedmont musician who was their mentor]. It was the apprentice model, learning this style, which we don’t play with anybody else. And I just realized, if one of us gets hit by a bus tomorrow, this is gone. Obviously, Joe Thompson taught a lot of people, but the fact that our fiddle-and-banjo interlocking does what it does is because we sat with Joe. It’s one thing of many that is worth preserving. And I thought, we need to capture it in an old-time way. We wanted it to sound like you wandered up onto our porch and sat down and we just played some tunes.”

And that describes the aural vibe here. You can hear the roots of Black string band music in both bluegrass and traditional country, but the joyous and evocative music here precedes both. Recorded outdoors (during a locust brood), you hear birds sing, insects buzz, and gentle breezes blow as Giddens and Robinson play and sometimes sing traditional tunes with a warm and engaging virtuosity. “Hook And Line,” with its tight yet loose arrangement and call-and-response vocals, is a standout, as is “Pumpkin Pie,” where Giddens exclaims, “This is the sound!” Robinson takes the lead in a majestic take on “Little Brown Jug,” and they harmonize vocally on “John Henry,” Giddens’ propulsive playing alluding, with passion, to the lyric “dying with a hammer in his hand.” Her plucking really shines on “Marching Jaybird” and his fiddling soars as it drives “Ryestraw.” “Walkin’ In The Parlor” is an apt capstone to the album — this down-home hoedown is as satisfying as a snack of cornbread and buttermilk.

— Mark Hanser

Jazz

In his liner notes for Unclassified Affections, the new disc (PI Recordings) from the Dan Weiss Quartet, drummer/composer Weiss concludes that he could have played the ending to “Dead Wall Revelry,” the last cut on the disc, “for thirty minutes without being bored.” That would have made for great listening, but this disc is more disciplined than that — it supplies briefer but still affecting snippets of sublimity.

In his liner notes for Unclassified Affections, the new disc (PI Recordings) from the Dan Weiss Quartet, drummer/composer Weiss concludes that he could have played the ending to “Dead Wall Revelry,” the last cut on the disc, “for thirty minutes without being bored.” That would have made for great listening, but this disc is more disciplined than that — it supplies briefer but still affecting snippets of sublimity.

Acclaimed vibraphonist Patricia Brennan, guitarist Miles Okazaki, and trumpeter Peter Evans join the leader on eight of his originals.

Brennan, since she emerged a few years ago, has specialized in maintaining a strong presence, juggling intensity with a sort of ethereal ebb and flow that alternately mystifies and entices. She leads off the disc’s title track with an arpeggiated solo before Okazaki and Evans enter with bursts of spontaneous sputters. Weiss joins for a passage of collective improv and the parameters of the band’s approach to the repertoire have been set. That is, the musicians lean toward a mesmerizing mellowness that is occasionally interrupted by spates of assertiveness. (This is, after all, a drummer’s record, so there has to be some thump here and there.)

The band cuts loose a bit on “Holotype,” a track that hops and skips through a winding path of free-bop to free-form, wrapped up by the leader’s solo, a percussive recap that is followed by resolution. In “Mansions of Madness,” Okazaki’s distortions go staccato while Evans displays his always interesting tempestuousness. Off-kilter funk defines “Existence Ticket,” which floats around Evans’ muted trumpet. Brennan, again, proffers plenty of mystery.

Brennan creates a chamber-like feel with chiming overtones in “Perfection’s Loneliness.” “Consoled Without Consolations” gives us the foursome embracing a collective lighter touch that reaches the album’s peak of delicate interaction.

The aforementioned “Dead Wall Revelry” is propelled by urgent syncopations before it calms down into a dreamy close. The track makes you long to hear a little bit more from a fine band that is inclined to churn out moments of dazzle rather than settle in and focus on the rewards of long-form coherence.

— Steve Feeney

Visual Art

George Romney, “John Flaxman Modeling the Bust of William Hayley,” 1795 to 1796, Oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The title — Romney: Brilliant Contrasts in Georgian England — suggests the contradictions the exhibition aims to illustrate. Installed in a single room high in the labyrinth of the Yale Art Gallery, the exhibition was created to complement the new installations at the recently reopened Yale Center for British Art nearby.

As the son of a provincial cabinetmaker, George Romney was once the most fashionable portrait painter in Georgian London. Yet he refused to join the Royal Academy or participate in its mutually self-congratulatory politics. He aspired to be a history painter, but rarely got beyond the planning stages. His fifteen-foot composition illustrating Shakespeare’s The Tempest contained more than twenty figures, but it was destroyed in the 1950s “due to poor condition,” according to the show’s curators. A study of Miranda, Prospero, and Caliban in the midst of the titular storm, quickly sketched in swirling, dark ink washes, hangs in the show.

The exhibition includes portraits in Romney’s relaxed, glassy-surfaced, neo-classical style, but the real stars are the drawings. Rapid, vigorous, expressionistic, dark, and sometimes nearly abstract, they seem to leap ahead a generation, diving into the thick of English Romanticism. Artists William Blake and John Flaxman were close friends and admirers of Romney, as illustrated in his last major painting, John Flaxman Modeling the Bust of [the poet and biographer] William Hayley. Several of Flaxman’s atmospheric drawings are hung nearby to underscore the Romney influence. Blake referred to his friend as “our admired sublime Romney.”

Today, Romney is less well known than many of his contemporaries and competitors, including the academicians Gainsborough and Reynolds. Yet this show, small as it is, suggests that he was far more than an also-ran and, on the whole, might have been the most interesting of the three leading portraitists of the era.

— Peter Walsh

Design

“Seated Cabinet,” John Dunnigan, 2024, white oak. Photo: Gallery NAGA

Gallery NAGA, one of the few remaining art galleries on Boston’s Newbury Street in the Back Bay, was founded as an artist cooperative in 1977. In 1982, Arthur Dion was hired as the director of Gallery NAGA. Often considered the godfather of studio furniture, Dion led the gallery for thirty distinguished years. Meg White now serves as director, continuing the gallery’s legacy.

NAGA’s primary focus is contemporary painting, as well as exceptional contemporary photography and printmaking. It has also assumed a special position in the local, regional, and national art world as a premier showcase for studio furniture, presenting unique and limited-edition handcrafted pieces.

Studio furniture combines furniture design and sculptural creativity with a painterly flair. Studio furniture practitioners are master craftsmen dedicated to making handmade functional objects of the finest quality. These pieces, while usable, also reflect a distinctive intellectual and emotional vision. The best studio furniture is aesthetically complex, marked by individual expression, metaphorical resonances, and even a touch of social conscience. For decades, Gallery NAGA has represented one of the world’s premiere studio furniture creators — Judy Kensley McKie.

From June 6 through July 11, Gallery NAGA will present recent work by John Dunnigan. A longtime professor at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), where he co-founded the Department of Furniture Design, Dunnigan has worked as a studio furniture artist for over five decades. His works in the show “Possible Necessities” demonstrate brilliant craftsmanship, exemplary technical skill, and an eye for physical grace. However, the pieces, which include chests and chairs, while extremely elegant, also reveal a certain soullessness. The titles of the pieces—such as “Rising Water Chairs,” “H2 Chairs,” and “Wildfire Loveseat”—suggest a strong concern about climate change, though this does not necessarily translate into an effective environmental message. A chair remains a chair; three chairs stacked together do not serve as an effective warning about global warming. Still, the finely wrought objects in this exhibit are well worth appreciating for their beauty.

— Mark Favermann

Books

“Beautifully written, charming, honest and melancholy in equal measure, this book is both a delight and deeply thought provoking.”

“Beautifully written, charming, honest and melancholy in equal measure, this book is both a delight and deeply thought provoking.”

So says Simon Rattle, the renowned British conductor, about the new memoir from American composer Allen Shawn.

I keep my own remarks brief, because I know Shawn somewhat and suggested that he send the manuscript to University of Rochester Press, though of course it went through the usual process of pre-publication review by Confidential Outside Readers.

I want to say something about this wonderful book because I know that lots of Arts Fuse readers will find this account of how a composer finds his way informative and engaging. This will not be a surprise for anybody who knows Shawn’s first two memoirs: Wish I Could Be There: Notes from a Phobic Life and Twin (Viking; Penguin paperback). Shawn has also written elegant, insightful books on Arnold Schoenberg (Farrar, Straus & Giroux; Harvard paperback) and on Leonard Bernstein (Yale).

In short, this is a composer whose prose conveys the substance and specificity of a creative musician’s feeling-world. Shawn came with major advantages, including an excellent education (his teachers included Leon Kirchner, at Harvard, and Nadia Bloulanger), plus contacts with the worlds of literature and theater through his father, New Yorker editor William Shawn, and brother, actor-playwright Wallace Shawn. But he also came with a near-crippling fear that prevented him, at times, from accepting what now seems obvious: he was born to compose music and to write.

Now, with dozens of commissioned and recorded works (he composed the background score for his brother’s famous 1981 movie My Dinner with André) and a long teaching career at Bennington College (in Vermont), he has earned the right to relax—if that’s possible for a person with his emotional makeup.

I’ll let you know soon about his latest CD release, containing his Piano Sonatas 6-8 and three sets of no less remarkable Etudes for Piano.

— Ralph P. Locke

Paul Elie’s The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) focuses on the relationship — harmonious as well as fractious — between religion and art during the Reagan era, paying special attention to what he calls the “crypto-religious”: words, images, and motifs in artworks that “express something other than conventional belief.” The book isn’t divided into essays or chapters but into “tales” that examine artists that include Warhol, Basquiat, William Kennedy, Toni Morrison (Beloved), U2, The Smiths, and Martin Scorsese. Elie studies how, in a post-secular world, they drew on crypto-religious tropes to complicate and complement their creative — and often controversial –visions.

Paul Elie’s The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) focuses on the relationship — harmonious as well as fractious — between religion and art during the Reagan era, paying special attention to what he calls the “crypto-religious”: words, images, and motifs in artworks that “express something other than conventional belief.” The book isn’t divided into essays or chapters but into “tales” that examine artists that include Warhol, Basquiat, William Kennedy, Toni Morrison (Beloved), U2, The Smiths, and Martin Scorsese. Elie studies how, in a post-secular world, they drew on crypto-religious tropes to complicate and complement their creative — and often controversial –visions.

Elie’s analysis is unerringly thoughtful as he explores the narratives and history of Warhol’s Modern Madonna series; Scorsese’s explicit The Last Temptation of Christ; U2’s “Gloria” and their war songs; The Smiths’ album Meat is Murder; and Kennedy’s novel Ironweed (along with icons like Madonna and Prince). The argument put forward by the “tales” reflects the writer’s solid understanding of theory, theology (Christian and otherwise), and ’80s history, but there’s no set structure. The writing is stream-of-consciousness, so readers must accustom themselves to jumps in Elie’s trajectory. The Neville Brothers’ legal woes give way to rock legend Leonard Cohen’s use of biblical quotes. Czesław Miłosz’s and Daniel Berrigan’s poetry is discussed alongside best-selling conservative journalist Tom Wolfe’s rise to fame during Pope John Paul II’s reign and the AIDS crisis. Regarding the volume’s title, Warhol’s The Last Supper series is probed because it delves into Catholic doctrines surrounding the problem of homosexuality in the Church. But it doesn’t receive deeper consideration than what’s found in any of the other “tales.”

Problems with organization aside, The Last Supper does a good job of dissecting the tempestuous cultural politics of the 1980s, from the hateful strategies employed by the conservative religious backlash to the refreshing response posed by Pop art. This is an essential read for those interested in how art can take a stand when spirituality takes the form of a repressive ideology.

— Douglas C. MacLeod

J. Hoberman, for years the reigning film critic at the Village Voice, might be the Siegfried Kracauer of the 21st century. Plus, he’s more entertaining.

Like the renowned expatriate German film theorist whose From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film (1947) remains the consummate text on the historical and cultural interpretation of cinema, Hoberman has applied similar acuity — with his own brand of sardonic irony — on how Hollywood has reflected US political turmoil. His so-called “Found Illusions” trilogy — The Dream Life (2003), An Army of Phantoms (2011), and Make My Day (2019) — traced the secret history of the Cold War from 1945 to 1990 on the silver screen, while Film After Film (2013) took a sneak peek at the new millennium.

But his latest book, Everything Is Now: The 1960s New York Avant-Garde—Primal Happenings, Underground Movies, Radical Pop (Verso Books), has both a broader and narrower focus. In it, he covers the extended play version of the 1960s — from 1958 to 1971– as refracted in the avant-garde art scene in New York City. The national and world historical events have an eerily familiar feel, while the artistic echoes are works and movements far more ambitious, subversive, absurd, and assaultive than anything our tepid culture could dream of today.

The former includes an unending litany of assassinations, war crimes, riots, corruption, oppression, outrages, massacres, cruelty, censorship, and stupidity that reminds us that, as awful as things are now, they were just as bad before. The latter boasts a line-up of some of America’s most significant — and at times, silliest and most sanctimonious — artists: John Cassavetes, Ornette Coleman, Andy Warhol, Bob Dylan, Shirley Clarke, Norman Mailer, Amiri Baraka, Yoko Ono, Yayoi Kusama, Allen Ginsberg…

At times, Hoberman gets bogged down in the details. That’s understandable. A native New Yorker, he lived through this chaos as a young observer, and his occasional cameos in the book are always pointed and amusing. Like at the end, when he bumps into Alejandro Jodorowsky at a bookstore in 1971 after a second viewing of the director’s hallucinogenic Western El Topo (I ended up seeing it myself five times) and finagles a visit with the director in Mexico. He wrote a hilarious piece about it and, to his surprise, the Village Voice accepted it. That was in 1972 — he’d continue writing there for the next four decades.

–Peter Keough

Journalist and novelist Omar El Akkad’s One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This (published by Penguin Random House) is a scathing cross between a cri de coeur and a J’accuse. His target is the grievously apathetic American and European response to the deaths of women and children during Israel’s ongoing campaign against Hamas. El Akkad sees this blithe acceptance—or routine denial—of collateral damage as symptomatic of what he describes as “the mild, ethics-agnostic emptiness of modern Western liberalism.”

Journalist and novelist Omar El Akkad’s One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This (published by Penguin Random House) is a scathing cross between a cri de coeur and a J’accuse. His target is the grievously apathetic American and European response to the deaths of women and children during Israel’s ongoing campaign against Hamas. El Akkad sees this blithe acceptance—or routine denial—of collateral damage as symptomatic of what he describes as “the mild, ethics-agnostic emptiness of modern Western liberalism.”

An award-winning novelist (American War, What Strange Paradise) and journalist, El Akkad diagnoses what he argues is yet another damning revelation of the political and spiritual hollowness at the core of the Western world. He excoriates the amoral, profit-driven forces that are panicked by even the thought of disrupting the status quo: “The fear of some comfort disappearing collides with a different fear—a fear that any society whose functioning demands one ignore carnage of this scale for the sake of artificial normalcy is by definition sociopathic.” The latter fear is systematically repressed, by the media, political parties, et al.

With passion and poignancy, the volume argues that liberal society’s indifference to the plight of the people of Gaza—driven by the belief that some minorities’ existence is deemed expendable—is part of a process of desensitization that will be called upon in the future, as mass deaths from wars and the climate crisis become more frequent. Fortressed Western countries, El Akkad posits, will need to accept—without troubling guilt—the decimation of many in order to maintain their illusion of productive stability.

This valuable book will anger and discomfort many on the left who would rather not talk about Gaza or America’s complicity in war crimes. That is its Orwellian virtue, and El Akkad brings personal experience as well as fact and reason to his indictment of our moral retreat. [Those seeking a more intellectually and historically expansive study of how Gaza is challenging the facade of Western liberalism should read Pankaj Mishra’s The World After Gaza.] El Akkad’s advice may feel insufficient. He is vague about what to do if we choose to reject both greater and lesser evils, suggesting that the disgusted should take no part in what’s happening and simply walk away. Perhaps to create their own political parties or movements? It remains unclear.

But One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This succeeds as an eloquent polemic aimed at our growing collective callousness, a voice declaiming what poet Joseph Brodsky called “the unacceptability of the world.”

— Bill Marx

Classical Music

Beatrice Rana’s silver medal in the 2013 Van Cliburn Competition has, over the last twelve years, been more than justified. Indeed, in that time the Italian pianist has emerged as a bona fide artist, a fact that’s gracefully underlined in her latest recording, Beatrice Rana plays Bach (Warner Classics), which features four of J. S. Bach’s seven solo keyboard concertos with the Amsterdam Sinfonietta.

Beatrice Rana’s silver medal in the 2013 Van Cliburn Competition has, over the last twelve years, been more than justified. Indeed, in that time the Italian pianist has emerged as a bona fide artist, a fact that’s gracefully underlined in her latest recording, Beatrice Rana plays Bach (Warner Classics), which features four of J. S. Bach’s seven solo keyboard concertos with the Amsterdam Sinfonietta.

In all of them, Rana and her colleagues never lose sight of the fact that all music must dance. These concerti—in D minor, E major, D major, and F minor, respectively—do just that, often crisply and with vigor.

Rana’s take on No. 1, for instance, doesn’t stint on energy. Here, too, the pianist draws out an absorbing range of musical characters. This carries into her reading of No. 2, the finale of which includes enchanting sprays of light in the solo part’s radiant little turn figures.

Nor does Rana disappoint for displays of searching, inward playing. The E-major Concerto’s Siciliano offers moments of beautiful repose. So does the F-minor’s Largo, which sings with pristine purity.

The Amsterdam players evince a terrific rapport with Rana, matching her focused articulations and spirited sense of play in each work. The collective’s responsiveness to one another culminates in a vital account of the Concerto No. 5, whose dark, weighty opening movement is counterbalanced by a brisk, focused rendition of the finale in which the music’s tightly coiled energy finds its necessary release.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

What are the odds that one family might produce not one but two of a generation’s great pianists? In the case of the Kanneh-Mason family, they’re pretty high. The oldest of the seven kids, Isata, is an established keyboardist at the start of what one expects will be a brilliant career. Now her younger sister, Jeneba, is out with a stellar debut recording, Fantasie.

What are the odds that one family might produce not one but two of a generation’s great pianists? In the case of the Kanneh-Mason family, they’re pretty high. The oldest of the seven kids, Isata, is an established keyboardist at the start of what one expects will be a brilliant career. Now her younger sister, Jeneba, is out with a stellar debut recording, Fantasie.

The program mixes fare that’s familiar and rare, with two sonatas, one by Chopin and the other by Alexander Scriabin, framing the proceedings.

Chopin’s No. 2 is among the canon’s best known and Kanneh-Mason’s reading is impressively fresh and unpretentious. The outer movements are well-directed, the first rich-toned while the second blusters with smart clarity. Contrasts rule in the Scherzo, whose stormy outer thirds here frame a lovely, songful Piú lento. Meantime, the famous Funeral March unfolds with stately pomp and a welcome sense of momentum, even in the inward middle section.

Scriabin’s No. 2 makes for an unexpected pairing and benefits from a similarly insightful approach. Kanneh-Mason’s lithe, flowing, beautifully voiced account draws out not just a range of color from its pages but also the music’s little quirks of phrasing and structure.

She also makes stylish work of four preludes—two each by Scriabin and Debussy (her take on “Bruyères” is conspicuously witty)—as well as a pair of Chopin Nocturnes. Those two, Nos. 7 and 8, are both shapely and fervent. Filling out the recording are a noble, sweeping rendition of Florence Price’s Fantasie Nègre No. 1 and highly characteristic interpretations of Margaret Bonds’ Troubled Water and William Grant Still’s “Summerland” (from Three Visions).

— Jonathan Blumhofer

One of the enchanting strengths of Philip Glass’s output is its sheer versatility: much like Bach’s, his music can be made to fit with the ensemble for which it was originally conceived (say, the Philip Glass Ensemble) or any number of others. Enter Aguas de Amazonia, the 88-year-old master’s quarter-century-plus-old score originally written for the Brazilian troupe Uakti but now repurposed by Third Coast Percussion and flautist Constance Volk (Rockwell Records).

Conceived in partnership with choreographer Twyla Tharp, this new version of the composer’s homage to the Amazon and its tributaries emerges as not just one of Glass’s true gems. It’s also one of the most haunting, absorbing, and satisfying works of any major composer these last thirty or forty years.

Much of the credit for this goes to Third Coast, for the sheer range of colors and textures they have built into their arrangements. There’s a rhythmic edge to the quartet’s playing that, it’s true, we’ve come to expect. But the sheer, taut brio of these performances command the ear and, ultimately, the heart.

The same can be said for Volk’s contributions, which are improvised over Glass’s notated structures. Her efforts are consistently gripping: fresh, vibrant, and exhilarating—particularly her contributions to the two Madeira River sections and her figurations over the pulsing tattoos in the Japurá River movement.

The end result is, if not this troubled year’s most life-affirming and hopeful release, then at least one of them. At the very least, it’s an encouragement that, despite seemingly insurmountable odds, the majesty of the natural world—not to mention the better angels of our human natures—might somehow endure.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Concert

Allegra Weingarten of Momma at the Sinclair. Photo: Paul Robicheau

It would be hard to find two more complementary young bands than Momma and Wishy, both led by dual singer/guitarists while echoing 1990s rock with nods to grunge, shoegaze and dream-pop at a long-sold-out Sinclair on May 28.

Momma surges forward with their fourth album, Welcome to My Blue Sky, as the California-by-way-of-Brooklyn band, fronted by Allegra Weingarten and Etta Friedman, continues to grow beyond comparisons to Veruca Salt. As on record, Momma began with the drony strum of “Sincerely,” Weingarten on acoustic guitar before joining Friedman on electric for standout “I Want You (Fever),” though the infidelity-inspired tune’s alluring chorus missed the album’s synth-encrusted punch.

But the foursome’s sparse dynamics and cool attitude surged in older rocker “Biohazard” (with Weingarten curling a double lick over Friendman’s chords), “Last Kiss” (bassist/producer Aron Kobayashi Ritch bolstering its grungy riffs) and “Rodeo,” where drummer Preston Fulks accented its stuttering volleys. The guitarists crouched to coax pedalboard effects to cap the nostalgic “My Old Street.” And by a sunnier cruise through “Speeding 72” (name-checking a Pavement song) to cap its 70-minute set, Momma provided raw charms, even if the group wasn’t as strong live as on record and didn’t stretch far beyond its influences (Momma gets another local chance to impress when opening for Pixies at MGM Music Hall at Fenway on July 18).

In one contrast, Wishy presented a co-ed front where Kevin Krauter and Nina Pitchkites split vocals and electric guitars, though Pitchkites’ soprano stood out in evoking the ethereal vocal/guitar blend of the ’90s British band Lush in “Persuasion” and “Triple Seven.” The Indianapolis quintet displayed a broader textural range within a settled groove, also suggesting folk-grunge during its 40-minute opening slot – and likewise making Wishy a curious band to watch.

— Paul Robicheau