“I like maps, because they lie.

Because they give no access to the vicious truth.

Because great-heartedly, good-naturedly

they spread before me a world

not of this world.” – Wisława Szymborska

This stanza from Szymborska’s poem Map, the last one she wrote before she died, loomed large in my head when I drove home after a conversation with an artist who had invited me for a studio visit to explore the project she is working on.

Kristie Strasen is a renowned colorist and textile designer, with numerous awards under her belt, and, more importantly, decades of experience in creating pattern and color schemes for high-end textiles where execution matches her original visualization. In the decade or so since she relocated from New York City to the Columbia Gorge, she has infused her creativity, her skill set(s) and her curiosity about the history of her new home into ever more ambitious projects at the loom.

Her current endeavor can be described as a work of cartography, in the widest sense. The weavings model reality in the most abstract ways, combining scientific inquiry, aesthetics and technique, as all map-making does that tries to capture reality in spatial form.

River Stories, set to run June 8-Aug. 20 at the Columbia Gorge Museum in Stevenson, Wash., will depict the entire course of the Columbia River from the Canadian headwaters to the mouth where it enters the Pacific Ocean, plus some of the tributaries, like the Klickitat and the White Salmon rivers, and several sections of the Columbia Gorge Scenic Area.

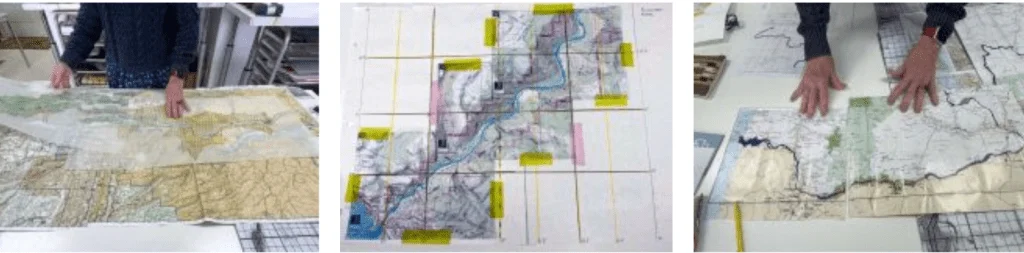

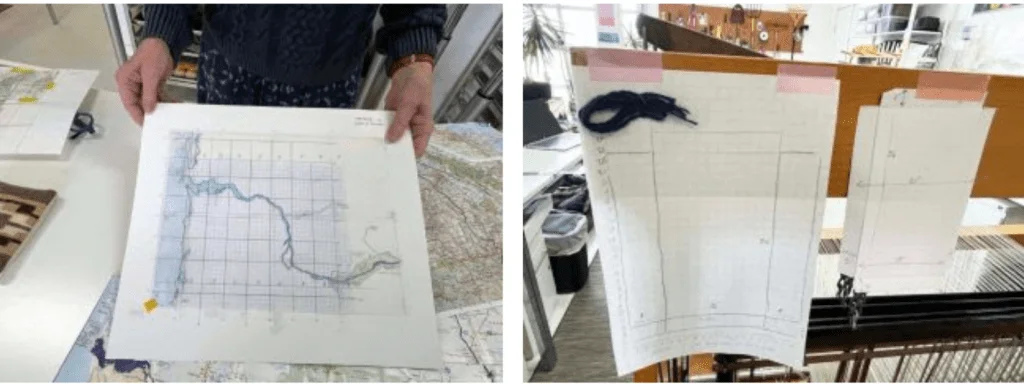

It is technically a complex endeavor. Strasen enlarged maps that show the geographic features of the river course, bends and all. She partitioned the sections into grids and then traced the river course, eventually with dots under the warp of her loom.

With free-hand weaving she delineated an exact depiction of how the river runs, through six sections, with background colors reflecting the tone of the respective landscapes, the forests, the cliffs, and the eventual softness at the confluence. The color choices required more than just her perfect eye: Because the wool in the requisite colors was of different weight, the straight edges, pride of accomplished weavers like Strasen, had a tendency to be less than perfectly straight once off the loom. Probably only detectable for experts, but something the weaver had to grapple with given her high standards.

All I can say: The tapestries are aeautiful, but I equally marvel at the way Strasen transforms her curiosity about the world into a specific work of art that shares some of her insights with the viewer.

Curiosity about the world: In addition to a longstanding fascination with maps, the artist devoured the literature about the history of the Gorge, the consequences of Western expansionism, and the effects of human intervention on nature, once she had arrived in White Salmon, Wash., and made it her home. She felt called to draw our attention to both the consequences of our meddling with nature and the preservation of it, the latter largely due to early efforts of individuals like Nancy Neighbor Russell, who was instrumental in rescuing the Columbia River Gorge in Oregon and Washington, when they were threatened by commercial interests. Russell founded Friends of the Columbia Gorge in 1980, working to protect the Gorge from development and secure it for federal protection, the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1986.

***

Maps express particular viewpoints in support of specific interests. They can shape our view of the world and our place in it by selectively presenting information. This can be bad when the purpose of persuasion is manipulation. I had written about this some years ago in the context of another map-making and art project:

“The goal of suggestive mapping was to achieve political objectives (while avoiding lies, which could be easily exposed) by appealing to emotions and rigorously excluding anything that didn’t support the desired message. Its maps were intended specifically to engage support from the general population, and they were often shamelessly explicit. Cornell University has a wonderful introduction and collection of maps all sharing the purpose of persuasion. The topics range from religion, imperial geopolitics (think colonialism), slavery, British international politics, social and protest movements to, of course, war. The goal was made explicit in the 1920s (and later taken on in force by the Nazis) when in reaction to the shameful defeat in WW I, German cartographers decided to go for the “Suggestive Map,” cartographic propaganda which they thought had given the British a strategic advantage.”

But the way information is presented can also have the positive impact of a warning or an invitation to think things through critically. A selective tool used by Strasen is the color she chose to mark the various dams blocking the natural flow of the river. In my interpretation, bright red bars signify the danger, the concept of halting, the possibility of destruction and the ongoing heat of the discussion around the justification (or absence thereof) of dam removal.

These visual magnets emphasize obstructions that we now know had ongoing disastrous consequences for fish populations, in addition to the trauma of displacement for the Native American tribes affected by the dam construction. They remind us how much the lifeblood of the Pacific Northwest, this river and all who it serves, are endangered by efforts towards relentless extraction, a view shared with the Columbia River Keepers, who are passionately engaged in its protection.

***

Maps in art have been around for some time (for a short history of this intersection, go here.)

Art, like maps, can be a tool of persuasion, doubling the force of that intention when utilizing maps’ suggestive power, which can be done in a number of ways.

Mona Hatoum, born in Lebanon to Palestinian parents and living in England, for example, took copies of the flight route maps you find in airplanes and added hand-drawn designs in ink and gouache. Rather than focusing on geographic borders, she delineated the movement across the globe, leaving to us the decision of whether that movement was voluntary or not. She herself describes the paths she drew to be “routes for the rootless.”

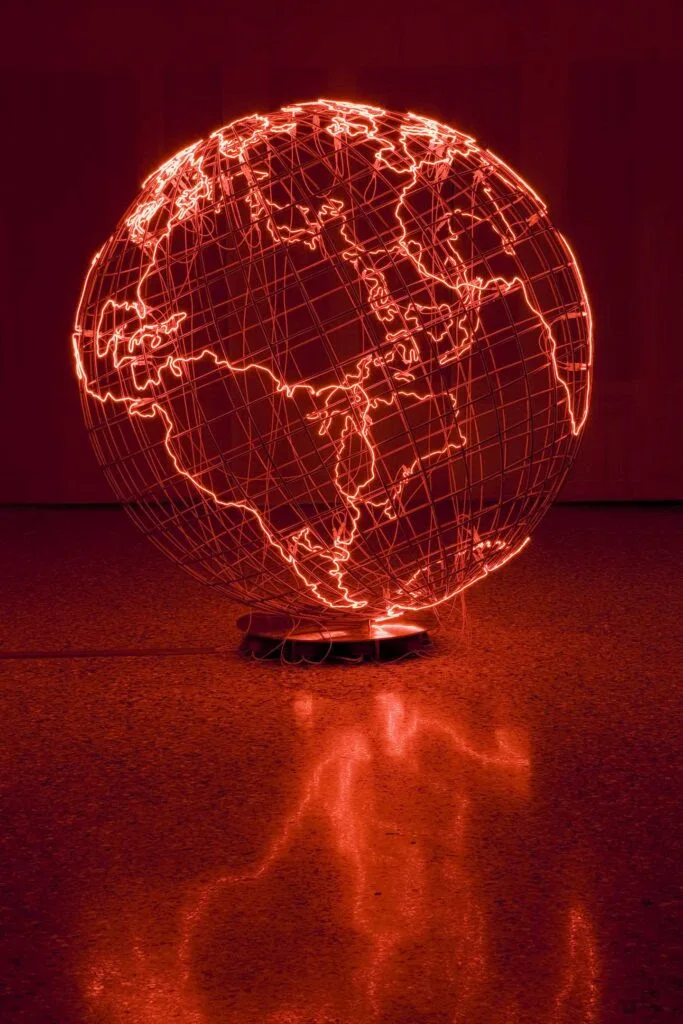

Later work employs sculpture, with red neon outlining the continents, representing a globe riddled by hot spots, places of military or civil unrest, a world aflame.

Closer to home, Los Angeles artist Mark Bradford has made his mark with his large-scale mixed-media works that combine representations of geography and the ruinous fate of residents of depicted areas. The artist models the streets and buildings of specific neighborhoods with string or caulk, layering scavenged paper on top and cutting and peeling away layers to both conceal and expose the geography. Some of his map paintings refer to areas in L.A. shaken by violence in the 1992 riots. Others refer to scorched earth, referencing the Tulsa Race Massacres of 1921, which wiped out Oklahoma’s Black Wall Street.

Not all art, of course, is explicitly political. Some, like Juan Downey‘s Map of America, draws swirls of color to stimulate the imagination.

Then there is Maya Lin’s Pin River project — sculptures depicting river courses with pins or marbles, up to 20,000 in this rendering of the Hudson river watershed. She also uses installations created from more than 200 bamboo reeds in the form of a 3D drawing of the Hudson River basin.

All of these works, in their own way, demonstrate that maps can be used for more than an efficient way to communicate spatial information.

This is also the case for Strasen’s tapestries, which are surely more than a tool to help us think about our physical surroundings. Her unapologetically reductive maps offer less context and more of a sense of wonder for a particular place, a particular beauty and history. A world not of this world, and yet.

The blue band of the river, set against an immense backdrop of diffuse landscape coded only in color, gives us a figure/ground constellation that tells a story emphasized by this degree of abstraction: the centrality of a river shaped by forces larger than us, defining a region, essential to its – and our own – survival.

The work will be completed in June when it will be inaugurated during a solo show June 8-aug. 20 at the Columbia Gorge Museum.

I cannot wait to see it hung!

***

This essay was originally published on YDP – Your Daily Picture on Friday, April 18, 2025. See Friderike Heuer’s previous ArtsWatch stories here.