Nowadays most of us depict a landscape by turning our cell phones sideways and snapping a photo. To commemorate the 200th anniversary of the founding of the Hudson River School of art, the Dorsky Museum has assembled works by four contemporary photographers, in a show titled “Landmines,” which opens February 8.

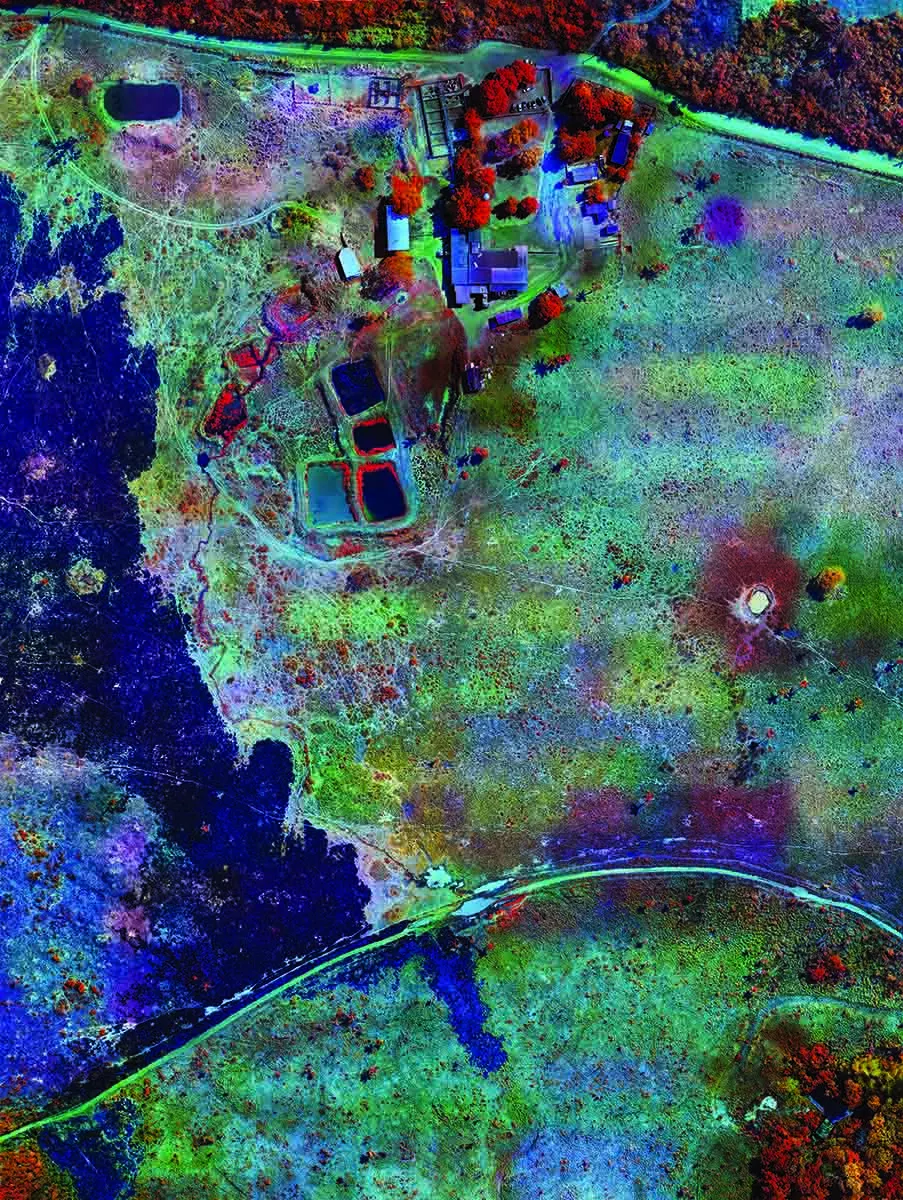

But these photographers are doing a lot more than wielding cell phones. In fact, they deploy some of the newest innovations in art photography. Irish artist Richard Mosse uses multispectral satellite imagery to show the environmental devastation in and around the Amazon Basin. It’s like seeing through a machine’s eyes, though the pastel colors are surprisingly gentle. Slaughterhouse, Rondonia (2021) recalls the abstract canvases of Richard Diebenkorn. Burnt Eucalyptus Plantation, Rondonia (2020) looks like a worn piece of Victorian embroidery.

The art most closely linked to the show’s title is Rick Silva’s. “Landmines” is, in part, a pun referencing mines extracting subterranean minerals. In his video Western Fronts (2018), Silva presents drone footage of four remote areas that lost their status as National Monuments under the first Trump administration, superimposing images of minerals lying beneath the soil. Elections have consequences, even for the innocent Earth.

The most topical work in the show is by Los Angeles photographer Christina Fernandez, who has spent years documenting migrant farmworkers in California. As we wait to see how many millions of immigrants will be deported by our new president, it’s sobering to view Untitled Farmworker (1989/2022), a solemn memorial to laborers who died from pesticide poisoning or were injured while working. Index cards bearing their names are embedded in soil, in neat rows, like artichokes or cabbages.

In 1825 the English artist Thomas Cole, fleeing the industrial desolation of Northeast England, sailed up the Hudson until he reached Catskill Landing. His paintings celebrating the majesty of his new home gave birth to the Hudson River School of art. If one could draw a picture of Manifest Destiny, it would look like a Hudson River School painting: a lush American landscape, bathed in the light of God. The Dorsky is a teaching museum as well as a community gallery, so numerous theoretical and historical issues are raised here. This exhibition could be subtitled “Manifest Destiny and Its Discontents.”

<a href="https://media2.chronogram.com/chronogram/imager/u/original/22708196/rondonia.webp" data-caption="Slaughterhouse, Rondonia, Richard Mosse, 2021, archival pigment print, courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

Slaughterhouse, Rondonia, Richard Mosse, 2021, archival pigment print, courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

To begin with, the virgin land Cole depicted was a myth. Millions of people already successfully dwelt on this continent, in large and small tribal groups. In 1818, for example, the Stockbridge-Munsee Indians of Oneida, New York, were forcibly removed to Wisconsin.

And the continent the Europeans conquered was not equally shared. Some rode westward in triumph; others trudged in chains. In 2019, MacArthur fellow Dawoud Bey photographed abandoned Louisiana plantations. “The history of trauma, of slavery, haunts them,” remarks Sophie Landres, curator and exhibitions manager at the museum, who curated the show. Architecture tells the bitter story: wooden shacks for the slaves, a genteel white mansion for the owners. Cabin and Spanish Moss is dominated by a venerable (oak?) tree bristling with moss resembling barbed wire, behind which a windowless cabin crouches. Black-and-white film—the only photographic medium available in the 19th century—gives the work a historical veneer. Also, black and white are the colors that defined American slavery.

“Landmines” begins with one of Thomas Cole’s sketchbooks from 1828, accompanied by a video showing its contents page by page. The show ends with Provenance (2023), an installation by Erin Lee Antolak of the Oneida Nation. A single moccasin rests on a pile of soil; nearby is a story, on paper, of Antolak losing a moccasin her mother made for her when she was a child—a loss symbolizing an entire lost culture.

Location Details