Leslie Jamison’s new memoir Splinters follows the aftermath of divorce and the awakening of motherhood, but it explores desire more than it does any kind of death. Jamison wants to make meaning, to connect, to love, to feel, to mother, to write, and to revise her life endlessly. There are losses and grief along the way, and the entanglements of marriage and motherhood are certainly recurring ghosts that haunt the narrator’s selfhood, as it spreads and ruptures.

The crystalline prose, absurdist humor, and everyday imagism that populate Splinters, however, continually draw us back to the memories and choices that make up a life, in all its messy, irresolvable variation and uncertainty. It’s not a book “about” divorce or motherhood, in other words, but about how we love and want, harm and repair, become and come undone, know and never can, endlessly.

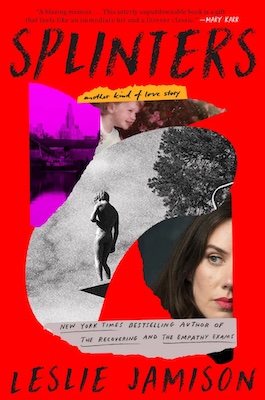

Jamison is, of course, well-established as a master of nonfiction. The Recovering is an epic treatment of addiction and healing; The Empathy Exams and Make it Scream, Make it Burn are each instant-classic essay collections. In Splinters, Jamison turns her equally practiced narrative eye on herself in her first memoir.

We corresponded about avoiding the binaries of motherhood, writing into shame, and how writing Splinters transformed her.

Amanda Montei: We seem to be having a moment with respect to literary and cultural representations of marriage and divorce, two subjects haunted by moralism. Men, monogamy, romance—all of these spin on an axis in the book, but ultimately, you write about resisting “the delusion of a pure feeling, or a love unpolluted by damage.” Is there something unique about nonfiction, or memoir specifically, that offers the opportunity to write away from such delusions? Your previous nonfiction draws heavily on personal experience, but this book is your first memoir. Did you always know this was the right approach to these subjects, or did you ever consider weaving research and criticism into this book?

Leslie Jamison: I’m grateful to you for this phrasing, haunted by moralism, because it gives me a new way to think about the role of ghosts in the book. From early on, I understood Splinters to be a book about haunting: being haunted by memories of my own marriage when it was full of love and promise, being haunted by the specter of another life in which my daughter was growing up in an unbroken family. (I often think that repeated words function as a psychic X-ray of a book, and in early drafts of Splinters I found the words “ghost” and “haunt” kept showing up over and over again.) But I think there’s a sense in which Splinters is also haunted by certain strains of moralism, too—certainly the notion of moral failure that can attach to divorce, but also the ways that parents, mothers especially, are expected to express their love by their children through various kinds of sacrifice. The book is reckoning with these ethical inheritances, and though there is certainly a vast and fascinating trove of cultural artifacts and histories I could have invoked in this reckoning—the unruly canon of divorce literature, the endlessly interesting (and moralized) history of divorce in America—I can say that this book announced its form and its scope to me quite early.

Splinters is so fully and deeply a book about wanting things, even as it also very much a book about caregiving and gratitude.

From the very beginning, I knew its form—these splinters of prose—and I knew its range: it wanted to stay close to my life, and my body; it wanted to get as deep into consciousness as it could. I wanted it to feel intensely distilled, intensely pressurized, utterly undiluted. When I turned toward cultural history—for example, writing a bit more about the women staying in Reno divorce hotels in the 1920s—the text felt allergic to these inquiries; they felt like grafts that didn’t quite take, like I was turning away from the heat and the pulse.

AM: I found your descriptions of the tedium and rapture of motherhood incredibly delightful—you’re able to capture the absurdity of motherhood and the strain, the many ways in which a mother’s identity is cleaved and confounded, without simply representing the relationship with the baby as a drag. Were there any specific maternal tropes you wanted to avoid while writing this book, or did you enter the process of writing about motherhood in some other way?

LJ: I truly loved your writing about motherhood in Touched Out as well, especially in this particular way: thinking rigorously about the ways many things can be true at once about intimacy and bodily closeness. More than anything, I wanted to avoid the binary I felt looming in so many representations of motherhood: either glorifying it at the expense of representing its hardship, or else somehow articulating this hardship in a way that seemed to efface or exclude its delight, profundity, and wonder.

With parenting, perhaps because it feels so intense, it can sometimes feel like you are compromising the force of a feeling by letting in another feeling as well, especially one that feels perpendicular. I wanted to let all the feelings in, which felt simply like paying attention to the ways they were already there.

There’s a moment in the book where I’m trying to tell my ex-husband about a day spent with my infant daughter at the Botanic Gardens, and realizing that the sense of wonder I’m trying to articulate somehow means that the exhaustion of the day is getting lost—but also really wanting to resist the idea that in order to make the labor visible, I have to narrate the whole thing as an impossible hassle. Why can’t it be wondrous and labor at once? That’s one of the milk-drenched battle cries of the book.

AM: Yes, I loved that moment in the book so much, and I felt that milk-drenched battle cry! Speaking of, desire is central to this book as well—the desire to be an attentive and present mother, but also the hunger for a sexual life, a creative life, a pleasurable life, and for a lover who will care for the mother. A mother who desires anything beyond motherhood is still, I think, quite radical (even though, of course mothers want!). I wonder if you felt the danger and subversiveness of such honesty as you wrote—or perhaps the necessity of it?

LJ: A lover who will care for the mother! Yes, please. Splinters is so fully and deeply a book about wanting things, even as it also very much a book about caregiving (offering others the things they need and want) and a book about gratitude (feeling grateful for many things I hadn’t even known I wanted.) Even as we live in the shadow of a certain hollow Reagan-era 80s feminism of women “wanting it all” and even “having it all,” I think there is still—as you say—all kinds of shame attached to maternal desire. Shouldn’t the mother be more worried about what other people want? She certainly shouldn’t want things that get in the way of satisfying the wants and needs of others.

The act of mothering my daughter has given me this incredible proximity to consciousness in formation.

Writing into that shame—or the cultural script that makes us feel susceptible to that shame—was absolutely one of the projects of Splinters, especially as I feel acutely aware that my ability to follow multiple veins of desire—wanting to be a mother, and an artist, and a teacher—is absolutely predicated on kinds of material stability not available to so many other mothers. To put it crudely: financial stability makes it possible not only to act on wanting many things but perhaps, even deeper down, to explicitly admit these desires, to grant them room in the psyche.

While there is difficulty in reconciling these identities— mother, lover, thinker, writer—the book also explores the creative transformation provided by motherhood. Can you share a bit about how mothering has altered your creative and intellectual practice, your perception of the world, your writing, or your sense of attention?

I think this is absolutely another trope of motherhood that I was interested in writing against: the narrative of motherhood and art as necessarily or unequivocally competing gods, always undermining each other in the finite economies of time and attention. There’s a way in which the mother-artist is always pitted against herself, insofar as the two identities on either side of that hyphen are often understood as locked in competition. Feed one wolf and the other starves. And I think it’s important to acknowledge the ways this is true: time and attention are finite economies. No one can clone herself (not yet at least) in order to simultaneously embark on an intricate crafts project with the kid and finish her novel at once. The ability to even try to do both things is often mostly dependent on being able to pay for childcare. All those constraints are real and shouldn’t be sugar-coated away.

But at the same time, there are ways in which motherhood has been transformative and deeply generative for my life as an artist, too—not just because I write about being a mother, but because being a mother has sharpened my curiosity, expanded the range of my investments, and pressurized my relationship to time. The last of these is the most pragmatic. Now that I have a daughter, and her wellbeing is the core of my days, the logistical non-negotiable, there’s a sense of stolen urgency that feels like a heat source underneath the hours of my days—time always feels like I’m moving toward the edge of a cliff, the cliff of running out of time, and that makes me work differently, more feral and focused and ferocious about the time I have.

As for investment and curiosity, here we go: the act of mothering my daughter has given me this incredible proximity to consciousness in formation. I mean, I truly believe that consciousness is always in formation—we are always changing, we are always dying and becoming—but a kid is learning what clouds are. She is learning that the heart of a whale is as big as a van. She is learning her own capacities for cruelty and compassion. She is learning what it means to have a second gummy bear and give it up. There’s so much to observe, so much to notice, so much to learn from what my daughter is thinking and imagining. (She is six now, and just recently made up an imaginary game she calls, “I think I’m right but I’m not actually right.” The very existence of this game seems like something I could think about for the rest of my life.) So there’s a way that she is teaching me, and asking me to pay attention, in ways that feel new and always renewing.

AM: I want to ask a question that is the inverse of the what do the men in your life think about this book, what will the baby think question. Here’s what I have: What did writing this book offer you? You write in one section about the importance of understanding what painful or complicated experiences do for us. Has writing this book opened up any other new perspectives for you on craft, creativity, work, identity, caregiving, or love, perspectives that perhaps you didn’t have access to when you began writing this book?

LJ: Writing Splinters has transformed me in so many powerful ways. Here are a few: It’s changed the way I think about memory—sharpened my sense of a certain give and take, where we go back into memory asking it to illuminate certain ideas we have about ourselves and our lives, and maybe it does that work, but it also ambushes us with bits of awareness or challenge we weren’t expecting. It’s given me a clearer sense of friendship and teaching as places where I wanted to direct my care and my love after my marriage unraveled. It’s given me a way to articulate and keep safe the love that existed in my marriage, by writing it down, and a way to hold the care I still feel for my ex-husband, by writing into the arc of witnessing him more fully as a loving and devoted father. More than anything, it’s given me a powerful framework and conviction for this gut-level knowledge I’ve always had, but didn’t always have language for—that I’m truly a student of my daughter; not in a saccharine or easy sense but in a profound and ongoing sense. I learn so much from her ways of being in the world, and from the work and joy of being her mother.

AM: This book is composed in fragments, but there’s a steady thrum of plot throughout the book as well. One discussion I often have with writing students who want to work in fragments is the necessity of creating some sort of backbone, or establishing some architecture, to sustain the work and pull the reader through the text. Can you share a bit about your process putting the three acts of this book together? What do you tell your students who work in this style about the possibilities or risks of creating a fragmented narrative?

LJ: I couldn’t agree more about the necessary thrum, and the crucial role of architecture in a fragmented work—not necessarily “holding together” the fragments, and certainly not arranging them into something linear, but giving a reader a sense of momentum and purpose. In Splinters, whose title refers to the form of the book (these narrative shards) as well as its content (memories lodged beneath the skin), I wanted to offer the reader two different kinds of momentum to move them through these whittled, glinting daggers of prose: There’s the narrative plotline of what happens—I have a baby, I leave my marriage, I build another kind of life in the aftermath—and then the emotional plotline of reckoning with central core questions: How do I hold joy and grief at once? How do I let my love for my daughter course through my days without feeling that the pain of my marriage ending should somehow negate it? How do I move between various roles (mother, lover teacher, ex-wife, daughter) without feeling split apart, or contradictory? I wanted these questions to feel like intellectual and emotional engines inviting or propelling a reader forward through the prose.

If plot is a way to ask a reader to come with you on a journey, then I think questions can also function as a different flavor of invitation: Come with me, as I try to reckon with this question, or learn how to live inside of it. Questions can also be a way to help readers find a place for themselves and their own lives in the text, even if they don’t share the particular experiences that it narrates. Even if someone has never had a kid, been married, been divorced, they have probably struggled—in some era of their living—with the question of living through pain and happiness at once, figuring out how to hold both. Asking that question in the text is a way of saying: If you’ve ever wrestled with this question, this book is for you.