She sat for a long time staring at the small lake that had been next to the brewery where once her family had produced some of the finest beer in Europe. A half hour earlier one of the last survivors of the Nazi incursion into this little nowhere town in middle Europe had led us to the brewery building where her clan had made a life before they were nearly all slaughtered in the various camps of wartime Europe. The place was a school now, and the plaque that commemorated the brutalities of seventy-some years earlier noted how the building had been turned into the town’s Gestapo headquarters during those years of the Polish resistance and heroism—but it said nothing about the Jewish family that had thrived there for generations.

I had tagged along on this trek to Poland, and later would accompany her to Russia and then Uzbekistan, because her father and aunt, mere children back then, had been part of an impossible exodus that had escaped the Nazi death machine but ended up in Stalin’s Gulags in Siberia, before marching three thousand kilometers to Uzbekistan to finally arrive in Iran, of all places, where the children were finally collected by the Jewish Agency and sent to what was then Mandatory Palestine.

Writing the novels that I wrote, from our oft-burning swath of the planet, meant I had to always walk that tight rope between reality and fiction.

We were colleagues in a university in New York. Two people from two countries as hostile to each other as ever was. Attraction has its own language. It defies history and current affairs, and time and space. Until, perhaps, it cannot push back against all of that weight anymore. Neither of us knew any of this back then. And when I finally made my move, her eyes seemed to say, “Alright, you son of a bitch, you have exactly three sentences to prove to me you haven’t an agenda and you’re not a fool.”

We became inseparable. In America, in New York, where you have to book weeks in advance in order to have coffee with someone you call a friend, we spent hours each week gossiping, Middle Eastern style, about everything and everyone that rubbed us wrong. We spoke the same language, even if Persian and Hebrew are about as far apart as two languages can get. Our lens was the same—a no-nonsense realism that came from having been born in a part of the world where theory means nothing, a geography where the span of a day can contain the obliteration of everything you have ever known, never to be recovered.

It was only natural that when she told me her father and aunt had been saved in my country—the country of the adversary—during WWII, that I would encourage her to follow their trail and write a book about it. I promised to help her with her research, particularly the Iran part where as an Israeli she could never enter. All of this we did. The research, the travel, her writing and rewriting a book that eventually turned into a seminal volume in the field of Holocaust Studies.

But it was that moment in that Polish town by the lake that I kept returning to ever afterwards. I wished just then that I could turn all the clocks of time back for her, for us. Even later on when in a corner of Central Asia in the dream-like city of Samarkand, one of the cradles of Persian civilization, we found the exact hut where her father and aunt had come close to starving all those years ago, it was still the moment back in Poland that kept coming back to me—the location where everything began and ended.

She had originally wanted me to tell her father’s story through fiction. But I insisted that this was her story, not mine. Besides, fresh calamities, as always, were already descending on our part of the world. Soon I was caught up in a new war that had me traveling for long periods of time, when I wasn’t teaching, with militias in Iraq/Syria. I was part writer, part journalist and sometimes active participant in this new war against zealots. She didn’t understand why I had to do this—why go rushing off to a war like that? Why not stay in New York and do more projects together? Because this war was too close to my home, was my answer. She of all people should understand this. More importantly, writing the novels that I wrote, from our oft-burning swath of the planet, meant I had to always walk that tight rope between reality and fiction. I did not have the luxury to throw myself in the lap of fantasy, or stroll casually in the aisles of research libraries. I needed my boots on the ground.

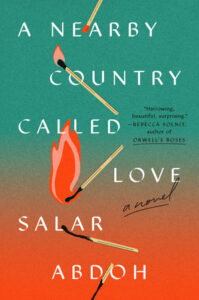

Our ways slowly parted. Because to have love for someone may never run its course, but to do something about that love does have a ticking clock. After writing the war book, I did an about-face and wrote A Nearby Country Called Love—a novel that, among other themes, explores the tenacious yearning for love. But also love’s failures in all the many wastelands where it is not permissible.

I’d used that poem to write a tribute to love in my fiction. A fiction that now had run smack against a wall.

I was in Beirut when she texted me. Another war had begun. It had been a while since we’d heard from each other and I knew why she was writing now. The war I’d gone to several years earlier had been in my backyard, this time the war was in hers. But in fact both of these wars, and all the other lesser wars that always seemed to surround our lives and the lives of our families and friends, had to do with a combination of us two; we were intertwined via our countries and their leaderships. Over the years we had argued our respective positions, sometimes in anger, but always with respect, and also with the acknowledgment that the magnetic pull we felt rose above all the rockets and missiles and suicide bombings and drone attacks and assassinations that might upend our lives irrevocably one day.

This time, however, it felt different. For once the death toll went truly beyond the pale, and I imagined she was somehow blaming me for all of this, and for my even being in Beirut (one of the heart centers of her enemies) at such a moment—and, most importantly, for having given myself over to war, rather than love, when the opportunity had been there to show an entirely different model for this topography of ours. I pulled the motorbike to the side of the road in the Dahieh district—an area of the city that the air force of her country had strafed at will countless times over the years—and began forcefully hitting the digital buttons of my cellphone in reply, in rebuttal, in fury and even in madness. In the meantime, life in Beirut’s Dahieh district was going on as if nothing were happening, though not very far to the south, on the border, artillery arounds had already been exchanged.

On the border, always on the border. My rambling text message was just another exchange of fire, wasn’t it? I deleted it.

“Nearby is a country called love,” the German poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, had written in his classic poem titled Go to the Limits of Your Longing. And I’d used that poem to write a tribute to love in my fiction. A fiction that now had run smack against a wall that would never let us get anywhere near the limits of our longings. This of course is one reason why people break walls down. I put the phone away, knowing it was the very last time we had written to each other, then I rode on deep into the Dahieh quarter wondering if I’d soon be hearing low flying jets breaking the sound barrier and coming this way.

___________________________

A Nearby Country Called Love by Salar Abdoh is available from Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.