- Author, journalist and conservationist Anil Adhikari focuses on grassroots conservation education by creating books for schoolchildren that feature local wildlife such as red pandas (Ailurus fulgens) and snow leopards (Panthera uncia), aiming to foster early environmental awareness and pride.

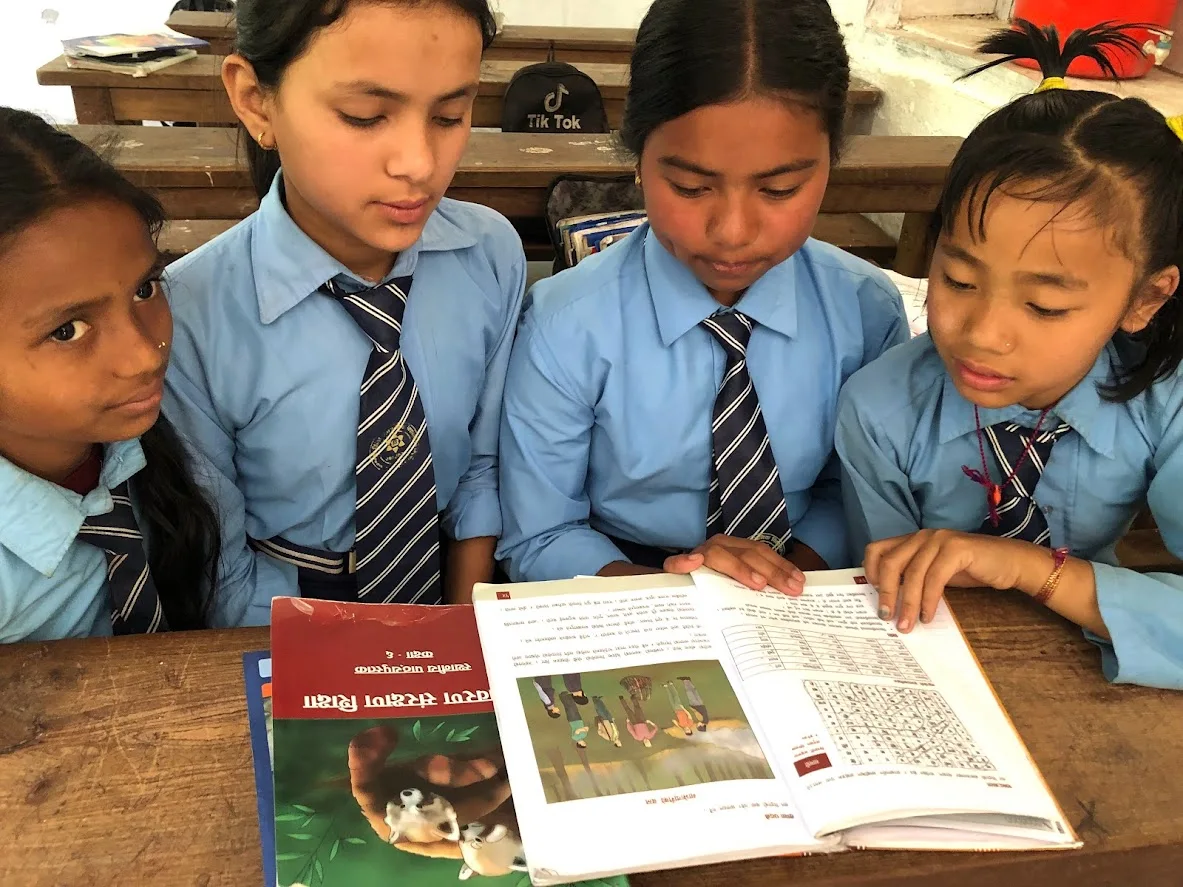

- Adhikari incorporates colorful illustrations and community-based stories in his books, making them more appealing and relevant for rural students whose traditional textbooks are often in black and white.

- He advocates for local governments to take responsibility for conservation education.

KATHMANDU — When discussing conservation in Nepal — home to iconic species such as the Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), snow leopard (Panthera uncia) and red panda (Ailurus fulgens) —awareness-raising among local communities often takes center stage.

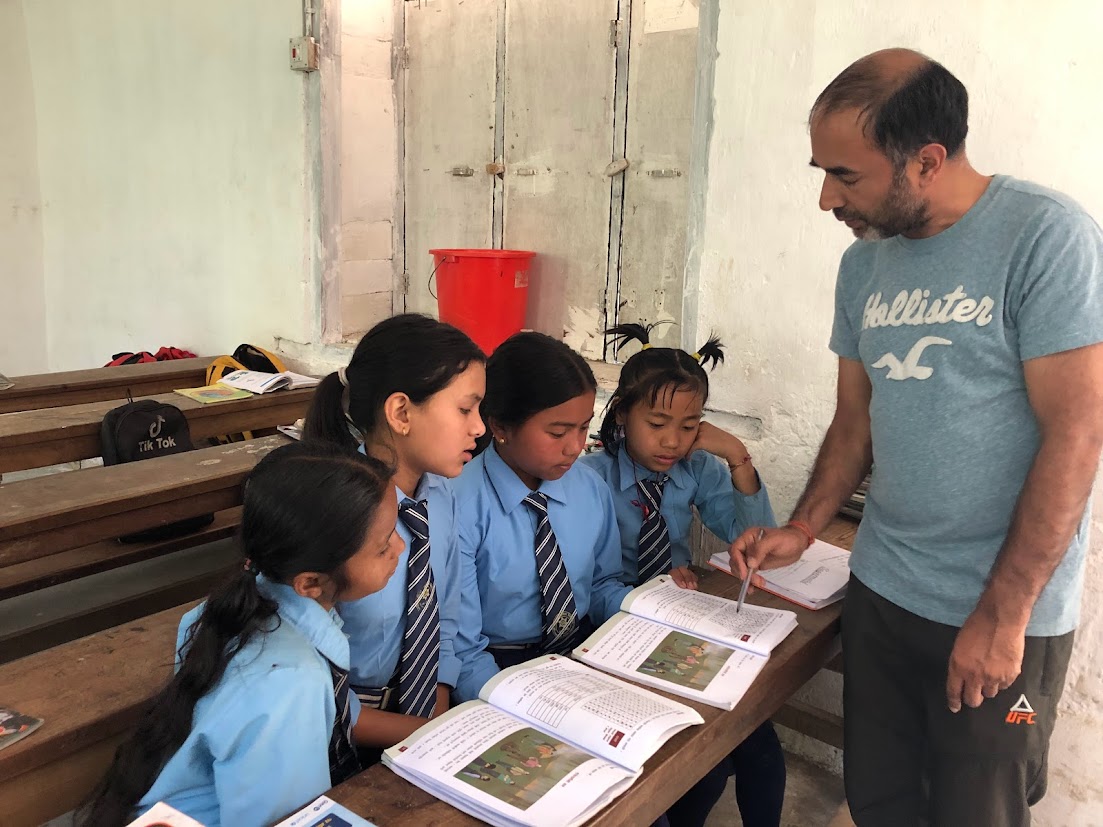

Many conservation projects conduct awareness programs through media including documentaries, books and pamphlets focusing on adults. However, journalist and writer Anil Adhikari takes a different approach, engaging with school children.

For Adhikari, who was working as a freelance environmental journalist, it all began in 2003 with a writing contract from WWF Nepal to produce a play book for school-based environmental clubs. The book, now in its fourth edition, has provided valuable lessons to students about different aspects of the environment they live in and the role they can play in saving it.

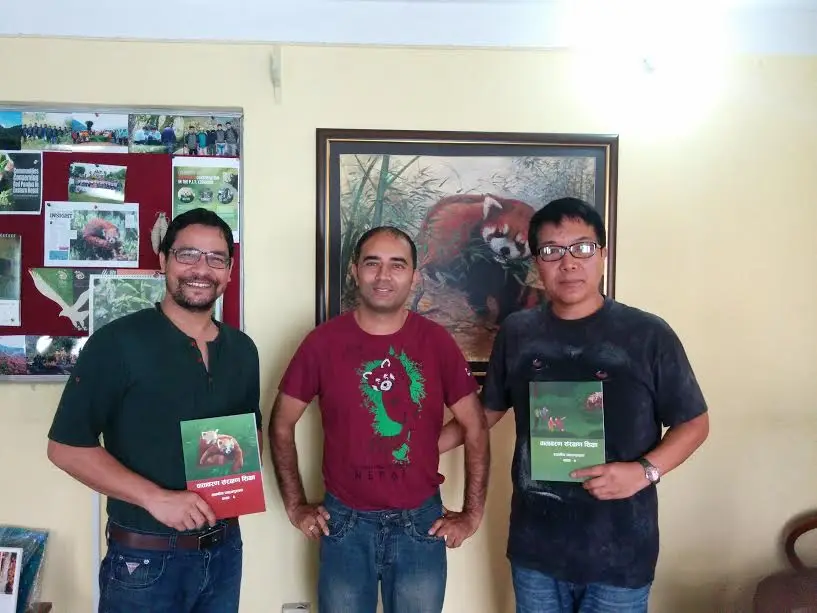

Over the past two decades, his conservation efforts have transcended species boundaries. He played a pivotal role in the Red Panda Network’s publication of two books now used in more than two dozen schools in eastern Nepal, supporting the protection of this endangered species. Similarly, his work is used by schools in snow leopard habitats to teach students about coexistence with the big cat.

Adhikari, who is also one of the editors of The Snow Leopard Magazine, says his experience has taught him the power of visuals when it comes to reaching out to schoolchildren. That’s why his books incorporate colorful illustrations and photos, making them captivating for young readers, especially in rural communities where traditional textbooks are often black and white. He is one of the recipients of the WWF Nepal Conservation Awards 2024 for “inspiring and educating hundreds of children, youth, and individuals on environmental conservation.”

Mongabay’s Abhaya Raj Joshi recently caught up with Adhikari in Kathmandu to talk with him about conservation awareness education in schools and its challenges.

Mongabay: Let’s start with your early days in conservation. Could you please tell us how it began?

Anil Adhikari: After finishing college, I was working as a freelance environmental journalist and writer when, in 2003, WWF approached me to produce a game book for school eco clubs. The job was challenging, as I had not studied science at the university. However, I used my journalistic skills to talk to different experts, community members and reference material to come up with the book in a few months’ time. The book is now currently in its fourth edition.

Mongabay: What was the book about?

Anil Adhikari: In the early 2000s, schools across the country, together with WWF, were establishing ‘eco clubs’ to make students aware about their surroundings and the environment. The book I worked on focused on making the children familiar with the habitats of different animals and how individuals play an important role in saving the environment. This was done through short skits and role-plays and other activities.

Mongabay: Seventeen years after the book was launched, you must have gained a lot of experience in the field. What are some of the challenges to conservation education in Nepal?

Anil Adhikari: Yes, it indeed remains challenging. Some teachers we worked with see eco clubs as one-time project works that they just need to get done with. But on the other hand, we saw that in schools where teachers and students took ownership of the idea of eco clubs, the clubs really brought behavior changes in both students and teachers.

Mongabay: Then, in 2017, you also worked on a book on red pandas for schoolchildren. How was the experience like?

Anil Adhikari: This book was a bit different from the eco club book, as it focused on red pandas and their conservation in their natural habitats in eastern Nepal. I prepared the book for Red Panda Network, an INGO that has been working in red panda conservation.

The eco club textbook allowed some flexibility in terms of classes and time — the teachers could get to it whenever they had time. But in the case of red pandas, the book was included in the class curricula, meaning the teacher had to conduct classes as per schedule.

To work on the book, we carried out questionnaire surveys among students, teachers and local community members to unearth their experiences and stories and best practices. They talked about red pandas dying in forest fires, students’ encounters with poachers and how they managed to report crimes. We went back and forth with the sources until we came up with a final draft and introduced it in 28 schools in eastern Nepal.

Mongabay: In 2020, you worked on a book on snow leopards. How would you describe the experience?

Anil Adhikari: The idea was to replicate best practices from the red panda experience. This time, Snow Leopard Conservancy agreed to fund the project. We held several rounds of discussions with the students, teachers and community members to come up with a syllabus for students attending schools in areas above 3,000 meters’ altitude in Nepal.

The difference between red pandas and snow leopards is that snow leopards are involved in conflict with humans at a larger scale, mainly livestock depredation. Therefore, it was a challenge to come up with a textbook that could make students aware as well as empathize with the animals.

Mongabay: In both the red panda and snow leopard cases, you prepared the books as part of some project. Was there this compulsion to tie everything to red pandas or snow leopards?

Anil Adhikari: To be very honest, these were books funded by donors under species conservation projects. We had no option but to focus on a particular species. But I think it is the job of the local municipal governments to come up with more comprehensive books to incorporate important environment and conservation issues facing the local people.

The new Constitution also gives local governments power to prepare and implement locally relevant courses for schoolchildren. I think the local governments should make use of this and introduce conservation-based courses in schools. That would make the whole effort more sustainable.

Mongabay: Why are local governments not working on it then?

Anil Adhikari: When we talk to the mayors of towns and chairs of villages, they tell us that it’s the job of protected area managers to come up with textbook production programs. In the case of the Annapurna region, they point their finger at the Annapurna Conservation Area management council as the officials responsible for the job.

But we have been advocating for a long time that local governments need to take ownership of this. That’s why during a Snow Leopard Day program, we organized a discussion on the introduction of a local government-level curriculum on snow leopards. On the radio programs we run also, we are advocating for the same.

It’s also not true that they aren’t doing anything. Take, for example, Mustang. They have started to teach the importance of snow leopards for a healthy ecosystem to schoolchildren through their textbooks.

These books, meant for students in grades six, seven and eight, were published by Nepal’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and implemented by the Teka Group Nepal, the organization I currently lead, with financial and technical support from Snow Leopard Conservancy.

We tell local governments that snow leopards are linked to tourism, economics and other social aspects of life here and they deserve to be on the curriculum.

Mongabay: In your opinion, are awareness activities more effective for schoolchildren or people outside of school?

Anil Adhikari: I believe that school education is more effective because we get to interact with the next generation of people. Also, the change that they go through is more visible and measurable; when we are in touch with schoolchildren, they talk about their learning with their other family members. They are quick to learn new things and excited to do so.

Mongabay: You said that printing the books, which are in four colors, has been a financial challenge as one book alone costs around 350 rupees (about $2.5), which a big amount if done at scale for a country like Nepal. Is it time to move on to multimedia videos that can be screened in schools — saving time and money?

Anil Adhikari: Yes, that’s a good idea. Books are indeed expensive. However, we’ve seen that children feel ownership of the books we give them, as the books are colorful compared to the black-and-white ones they get for other subjects.

Preparing videos is a good idea if we could incorporate animation into it, as kids like cartoons. It would involve a one-time cost, but disseminating it won’t cost as much. It’s an idea we’ll have to think about.

The other idea we are tinkering with is to provide books and training only to teachers so that we save on the printing costs and improve the effectiveness of the awareness programs.

Mongabay: What do you think is the best part of your job?

Anil Adhikari: Well, I had the opportunity to travel across the country, to places such as Sagarmatha (Everest) and Mustang to interact with local people as well as scientists.

During the course of my work, I understood that experts and scientists are more than capable of doing the job I do but they don’t have the time to do it. That’s where storytellers like us can step in to make a difference in communities.

Banner Image: Conservation storyteller and author Anil Adhikari with school students after setting up camera traps to study snow leopards in Mustang, Nepal. Image courtesy of Anil Adhikari.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Nepal’s top engineering, forestry colleges to align on development and conservation