One of the most well-known businesses in Waterloo is the Coe-Genung Funeral Home, once known as S.J. Genung and Son. To study the history of this iconic business is to learn the history of the mortuary business as it evolved in the United States.

Seth Johnson Genung ran a cabinetmaking business listed in the 1862 street directory as Stillwell & Genung Furniture Manufacturers on 9 Washington St. Seth Genung’s intricate carving and eye for detail helped his business reputation grow, and he became famous for the quality of his work. Some of his beautifully designed pieces include desks, piano cabinets, and furniture used for rituals at the Masonic Temple. These items are on display in the Terwilliger Museum at the Waterloo Library and Historical Society.

During this time period, most cabinetmakers would be commissioned to make coffins. Sarah, Seth’s wife, was a seamstress and would sew linings for the coffins and shrouds for the bodies. The coffins would then be delivered to the families who would take care of their own dead. The bodies would be washed on dining-room tables and then laid out for viewing in the parlor.

This began to change during the Civil War, when train travel allowed bodies to be shipped home in a fairly timely fashion. Bodies that could be identified and sent home needed to be preserved. The use of chemicals to preserve bodies had been introduced in the 1700s, though the process was not widely used until the 1860s, when horrific battles caused huge losses of life. Entrepreneurs would travel the battlefields with jars of arsenic, mercury, and other liquids to preserve the bodies.

Americans became fascinated with the science of embalming. This coincided with the growth of “spiritualism,” the idea that our loved ones could communicate from beyond the grave. The dead could be with us always, not just physically but spiritually as well.

The Lincoln factor

Embalming became even more popular after the assassination of President Lincoln. Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln were obsessed with spiritualism and embalming to the point where they actually watched Dr. Thomas Holmes embalm the body of Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth, a close personal friend. Holmes would eventually embalm the assassinated President Lincoln. While the three-week trip starting in Washington, D.C., took its toll on the embalmed body, its overall condition by the time it reached Springfield, Ill., was a scientific marvel.

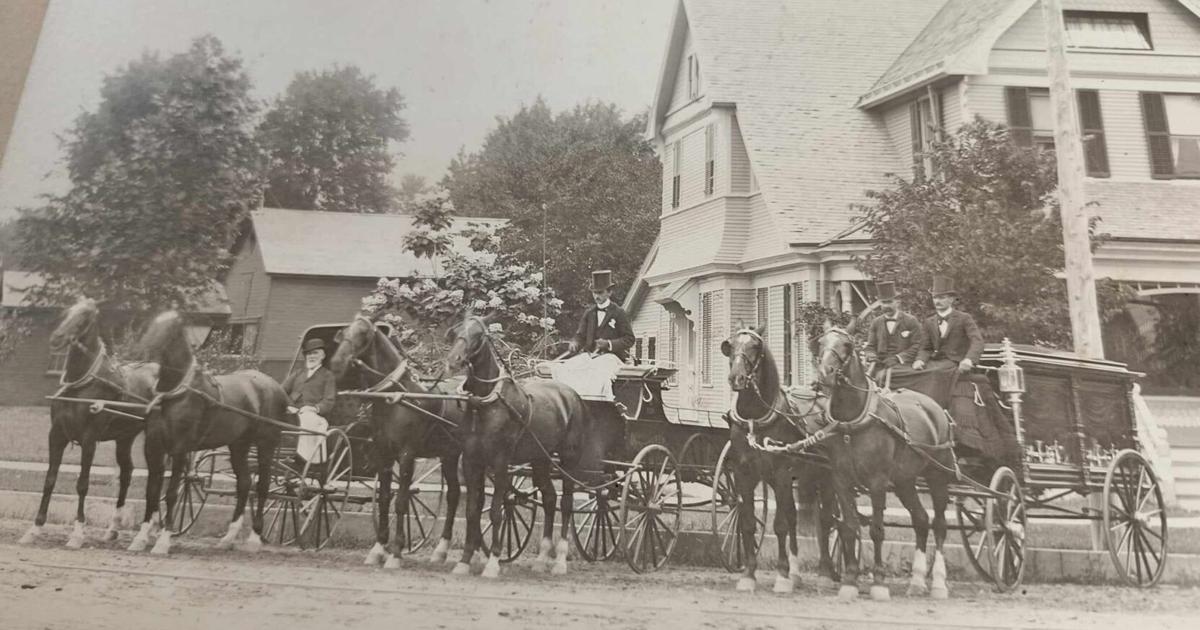

More people in the general public turned to embalming as a form of respect for the dearly departed. Now, instead of tending to a departed loved one yourself, the cabinetmaker came to the house and took the body back to the shop. The disinfected, embalmed body — safely ensconced in its coffin — would then be returned to the home for services.

Seth Genung became part of this booming new industry. The 1860 Census lists him as a cabinetmaker. By 1870, his official profession was listed as undertaker and furniture maker. The 1900 Census describes him as solely being an undertaker.

Soon, the mortuary business took another turn that affected the Genung family. The undertakers began to open their own homes for viewings and religious services as a cost-saving convenience for customers. In 1891, the Genung family built a large house on the corner of Park Place and West Main Street in Waterloo. This house was designed to conduct all mortuary business in one place, offering a one-stop shopping alternative for families. My father remembered his Grandpa William, who died in 1934, being laid out in our sun porch on Packwood Road. He was the last Edwards to be brought back to the family homestead for a funeral.

The Genung that made the family a household name was Charles Augustus Genung, Seth’s son. Charles, known as C.A., was a great innovator who filed a number of patents. One of his most important inventions was a new method of embalming that is still used today. He and his colleague, Howard S. Eckels, wrote “The Eckels-Genung Method and Practical Embalmer.” C.A. Genung lectured around the United States and Canada, teaching undertakers this new technique.

C.A. Genung turned the business of undertaking into a true mortuary science. He and Mrs. L.R. Simmons started the “Syracuse School of Embalming and Sanitary Science,” and C.A. Genung was a leader in his field and pushed to hold morticians to a high professional standard. After a train crash near Rochester that killed 30-plus people, he organized the local undertakers who worked nonstop for nearly 48 hours to repair and preserve the bodies of the dead, knowing that family members would be called upon to identify the remains. The undertakers wanted to ease the pain of that process as much as possible.

When C.A. Genung died, his son, Henry Genung, took over the family business. Henry’s son, Henry Jr., suffered a ruptured appendix at the age of 13. While he lay dying in the hospital, Henry Sr. saw the Catholic priest administering to some of his parishioners and asked him to come pray for his son, which the priest willingly did even though the Genungs were longtime Episcopalians. The priest then left the hospital and rushed to St. Mary’s School, where he had all the nuns stop teaching and pray for Henry Jr.

When Henry Jr. died the week before Christmas, the priest and all the nuns came to the Genung home to pay their respects.

Henry Sr. never forgot their compassion and kindness. Every Christmas after that, Henry Sr. sent Christmas baskets to all the nuns and priests residing in Waterloo, a tradition carried on by his son, John Seth Genung, and later by Roderick Coe, the present operator of Coe-Genung Funeral Home.

The Genung family helped create the community of Waterloo and, in doing so, made their mark on history.