Q: Does Columbia, New York City’s Ivy League university, established by royal charter as King’s College in 1754, have an art museum?

A: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, established in 1986, moved into the Lenfest Center for the Arts when the center opened in 2017 on Columbia’s new Manhattanville campus in West Harlem.

If you were unaware of the Wallach, you have something in common with about eight million New Yorkers — not to mention the rest of the U.S. population, outside of those with a Columbia connection. Why would a university in New York City need an art museum? You can’t throw a rock there without hitting one (please don’t).

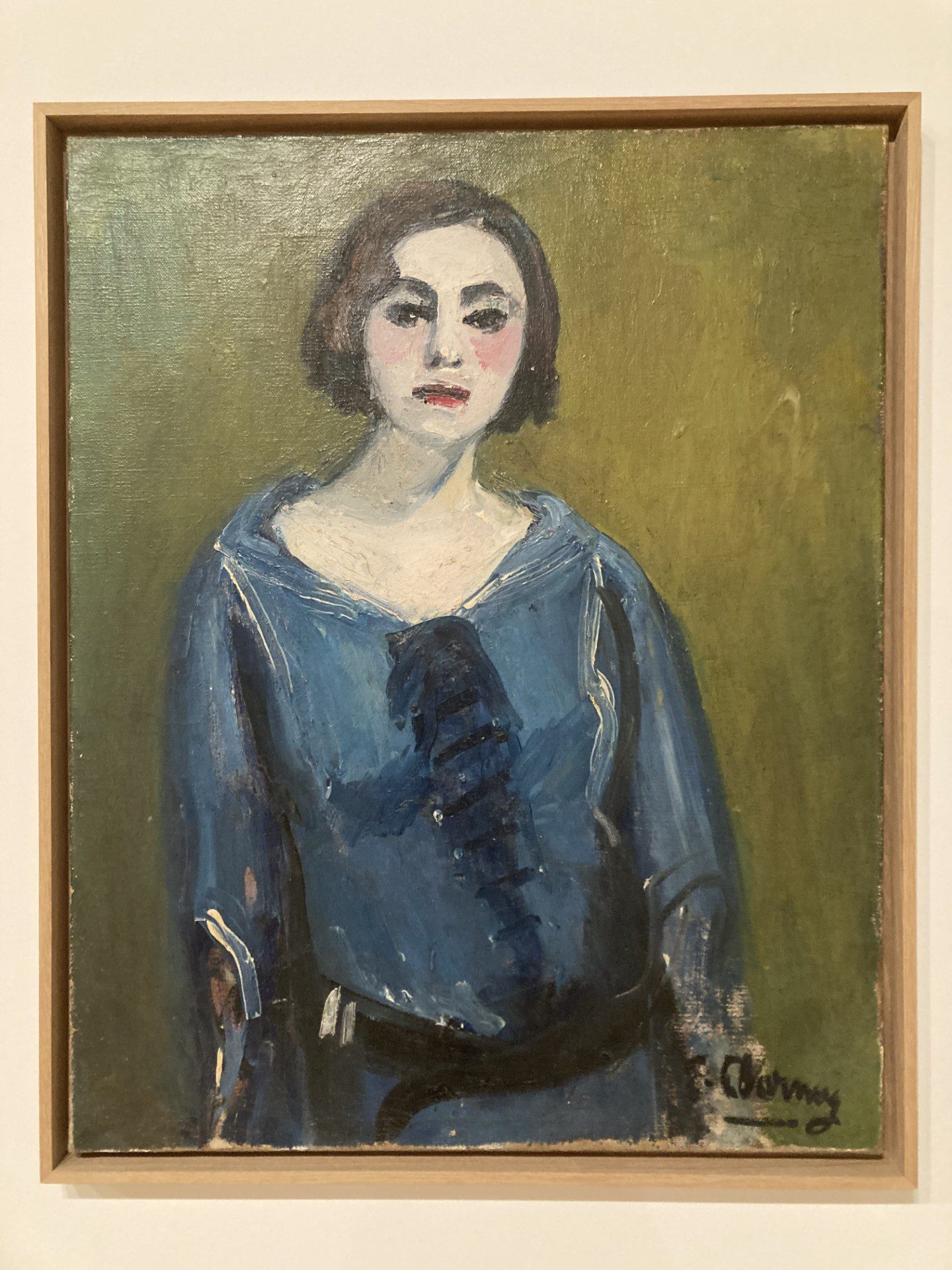

“Self-portrait,” 1906-7. Émilie Charmy.

Until last year, the existence of New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, like that of the Wallach, was largely unknown, even to frequent museumgoers. That March, the renamed Gray Art Museum, having relocated to larger space on Cooper Square, near Astor Place, opened “Americans in Paris: Artists Working in Postwar France, 1946-1962.”

The New York Times gave the exhibition a prominent review. And last fall, just before the opening of the second show at 18 Cooper Square, “Make Way for Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde,” the Times published an extended preview piece.

Named for Abby Weed Grey — who provided an endowment and donated modern art she collected on trips to Iran, India, Turkey and elsewhere — the Grey, which turns 50 this year, has arrived. (The museum also holds NYU’s collection of 19th– and 20th-century European and American art.)

Lovers of French art should make a point of visiting New York to see “Make Way for Berthe Weill,” which closes on March 1. Bonus: McSorley’s Old Ale House is two blocks away and around the corner.

Though essential to the artistic careers of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Raoul Dufy, Amedeo Modigliani, Diego Rivera, Marc Chagall and others — notably women artists receiving overdue recognition — art dealer Berthe Weill (the French pronunciation, BEAR-tuh VAY, rhymes with “way”) has been hidden in plain sight. She had the bad luck, under the circumstances, to be not only a woman, but unattached and unglamorous.

“Woman Holding Flowers,” 1934. Marie Laurencin.

In “The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas,” the 1933 memoir that Gertrude Stein wrote in the voice of her de facto wife, “Toklas” explains: “Matisse on the Quai Saint-Michel [the location of his studio] and in the indépendant [the Salon des Indépendants, where Matisse and other Fauves exhibited] did not know anything of Picasso and Montmartre [the location of his studio] and Sagot [Clovis Sagot, Picasso’s dealer]. They all, it is true, had been in the very early stages bought one after the other by Mademoiselle Weill, the bric-a-brac shop in Montmartre, but as she bought everybody’s pictures, pictures brought by any one, not necessarily by the painter, it was not very likely that any painter would, except by some rare chance, see there the paintings of any other painter. They were however all very grateful to her in later years because after all practically everybody who later became famous had sold their first little picture to her.”

Weill was born in Paris to a lower middle-class Jewish family in 1865. Short and bespectacled, she looked like the “Mademoiselle Weill who sold a mixture of pictures, books and bric-a-brac” that “Toklas” dismisses.

Working for her successful relative Salvator Mayer, Weill learned to deal in antiques. After Mayer died in 1897, she briefly ran a shop with a brother; obtained some early Picassos from Pere Mañach, the teenage artist’s promoter, in 1900; then, with Mañach’s help, opened her own Galerie B. Weill on Dec. 1, 1901.

Of the artists featured in Weill’s first show, sculptor Aristide Maillol is the only one with name recognition today. At right after you enter “Make Way for Berthe Weill” — five linked galleries, the first and last quite large — is a case holding three small figures and a bas-relief in terracotta by Maillol. Giving a sense of Weill’s “mixture,” another case displays a silver belt buckle, brooch and pendant by Paco Durrio, a Spanish sculptor, ceramicist and jewelry designer influenced by Paul Gauguin, with whom he shared a studio in the 1890s.

Although the Gray exhibition features other objects like these, and several cases of announcements, photographs, letters and related archival materials, there are roughly 100 paintings and drawings on the walls.

In addition to several early works by Matisse and Picasso, here are some highlights:

- Several paintings by the Fauves, given their “wild beasts” nickname by critic Louis Vauxcelles in a review of the 1905 Salon d’Automne. Vauxcelles, says the text, probably saw their work earlier at Galerie B. Weill.

- A beautiful 1907 painting — showing the influence of Gauguin, Cézanne and Matisse — of nude boys among tree trunks, a hilly landscape in the distance, by Béla Czóbel (a man), lent by a Hungarian museum.

- Diego Rivera’s 1914 Cubist painting of the Eiffel Tower, faint and in the distance, viewed through a crooked opening, with the colors of the French flag on a structure at right. Rivera’s first solo show in Paris was with Weill.

- A small Modigliani portrait, “Girl with red hair,” of 1915. In December of 1917, Weill gave Modigliani his first solo show, the only one during his (short) lifetime. The police closed it down because nudes visible from the street were painted with public hair.

- Self-portraits by realist Émilie Charmy from 1906-7 and c. 1916-19. Weill included work by Charmy, who became more of an Expressionist over the years, in two dozen exhibitions; several examples are in the first gallery.

- “Still life with Violin,” a first-rate Cubist work of 1918 by Polish-born Alice Halicka, who was married to Cubist painter Louis Marcoussis.

- Adjacent, contrasting 1922 portraits by Suzanne Valadon: one of a seated Madame Zamaron (wife of an art-loving police captain), regarding the painter/viewer; and the other, “Nude with a striped blanket,” of Valadon’s niece Gilberte, gazing downward.

- Marie Laurencin’s pastel-like “Woman Holding Flowers” of 1934, in which the flowers loom larger than the pale-skinned, sideward-peering woman. In Weill’s memoir (see below), the exhibition text notes, she wrote that when Laurencin came to her gallery wanting to meet a lesbian, “I didn’t dare admit that I didn’t know what that was.”

- Two unusual works by Chagall, whom Weill gave a solo show in 1927: a 1926 portrait of his wife, Bella Rosenfeld, embroidering beside a vase of flowers, in which blue and white dominate; and “The Birdcage” of 1925, on a dark green background, with a tiny rooster fiddling at lower right. The text suggests that it was painted for a group show with a Birds theme.

- Perhaps the showstopper, though it comes early on, is Dufy’s pink interior of 1931, inscribed “30 ans ou la Vie en rose,” honoring the gallery’s 30th

The exhibition’s title comes from the motto on Weill’s business card, “Place aux Jeunes,” meaning “Make Way for the Young.” The problem, from a financial point of view, was that she showed artists before most collectors were ready. And as the artists became recognized, the “big boys” — galleries run by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Paul Rosenberg, Ambroise Vollard and Georges Wildenstein — reeled them in.

“30 ans ou la Vie en rose,” 1931. Raoul Dufy.

Like Weill, the “big boys” (except Vollard) were Jewish, and faced antisemitism during the dozen years of the Dreyfus Affair, ending with Capt. Alfred Dreyfus’s 1906 exoneration. A fascinating section of the exhibition covers this us-against-them period, displaying prints, editorial cartoons, pamphlets and the like. Weill took sides by showing work by pro-Dreyfus artists; she wrote that Edgar Degas, whose studio was nearby, “would glare and ostentatiously turn his head away, spitting with contempt.”

In 1941, during the Nazi occupation, Weill closed her gallery and lay low. She was in such dire straits after the war that an auction was held in December of 1946 to raise funds to support her. Many artists, “all very grateful” in Stein-Toklas’s phrase, donated works. The proceeds lasted her until her death in 1951.

“Make Way for Berthe Weill” brings the directorial tenure of Lynn Gumpert to a brilliant close; director of the Grey since 1997, she will retire in April. Her co-curators were Marianne Le Morvan, founder of the Berthe Weill Archives; Anne Grace, curator of modern art at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, where the show goes on view this spring and summer; and Sophie Eloy, collections administrator and coordinator of the Contrepoints installations at Paris’s Musée de l’Orangerie, where it opens in October.

Both the exhibition’s accompanying book and a recently translated edition of Weill’s 1933 memoir, “Pow! Right in the Eye! Thirty Years Behind the Scenes of Modern French Painting,” are available for purchase in person and on the museum’s website.

Make Way for Berthe Weill

Through March 1

Grey Art Museum, New York University

18 Cooper Square, Manhattan

Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Wednesday, 11 a.m. to 8 p.m.

Saturday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.

greyartmuseum.nyu.edu

CAPTIONS

Photos by Richard Selden.

“In the Painting Salon,” 1933 (detail of a portrait of Weill). Georges Kars.

“Self-portrait,” 1906-7. Émilie Charmy.

“Woman Holding Flowers,” 1934. Marie Laurencin.

“30 ans ou la Vie en rose,” 1931. Raoul Dufy.