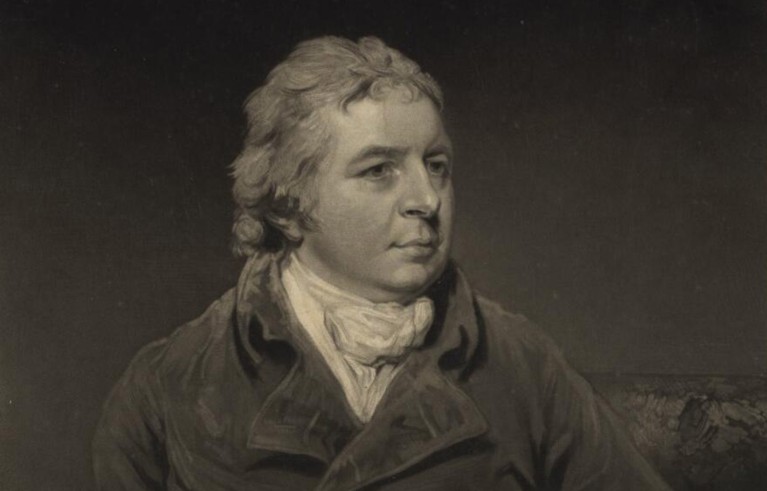

George Hibbert, an eighteenth-century English merchant who profited from the slave trade and fought abolition, lends his name to a genus of flowering shrubs.Credit: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales

Plant scientists are set to decide on whether to rid their field of offensive names.

This week, the group that sets the rules for naming plant species will vote on whether to rename dozens of organisms whose scientific designations contain a racial slur, as well as to reconsider other offensive names, such as those that recognize colonialists or people who advocated for slavery.

The votes at the International Botanical Congress in Madrid mark the first time that taxonomists have officially considered rule changes to deal with species names that many people find offensive.

I train farmers to use plant science in the fight against climate change

Advocates of the proposals argue that, as wider society addresses the veneration of people responsible for historical injustices, so should science. But some in the world of taxonomy worry that changing names en masse could sow confusion in the scientific literature, as well as create a ‘slippery slope’ that could threaten any species name recognizing a person.

“It’s very unfortunate that many of these names are offensive,” says Alina Freire-Fierro, a botanist at the Technical University of Cotopaxi in Latacunga, Ecuador. “To change the names that have already been published would cause so much confusion.”

Egregious names

Advocates of the changes point out that species names and taxonomy rules are constantly in flux — this week’s meeting will consider hundreds of proposals to alter rules for plant names. Eliminating especially egregious names is a drop in the ocean compared with the changes that already occur when, for instance, a genetic analysis splits a single species into multiple species or reveals new relationships between species, say scientists supporting the measures.

“It would be great to have some mechanism for weeding out some of the most offensive names,” adds Lennard Gillman, a retired evolutionary biogeographer and independent consultant in Auckland, New Zealand.

Every six to seven years, taxonomists meet at a conference called the International Botanical Congress to consider changes to the rules for naming plants, as well as fungi and algae (a separate group is responsible for animal names). Later this week, members of the Nomenclature Section will vote on two proposals that deal with culturally sensitive names.

New plant species are typically named by the scientists who discover them, with a key requirement that a description appears in scientific literature. During the nineteenth and even well into the twentieth centuries, the mostly European scientists formally naming species found in the non-Western world often recognized colonial rulers, such as the politician Cecil Rhodes, and patrons.

Yellow-flowered shrubs called Hibbertia, after anti-abolitionist George Hibbert, are one plant group that some botanists would like to rename.Credit: Robert Wyatt/Alamy

One of the proposals aims to rename an estimated 218 species whose scientific names are based on the word caffra and various derivatives — which are ethnic slurs often used against Black people in southern Africa — and to replace it with derivatives of ‘afr’ to instead recognize Africa. The second proposal, if approved, would create a committee to reconsider offensive and culturally inappropriate names.

Gauging support

In a ballot conducted ahead of the congress to gauge how much support there is for the hundreds of proposals, nearly 50% of voters supported changing the scientific names of plants such as Erythrina caffra, commonly known as the coast coral tree, to Erythrina affra. The proposal to create the committee sneaked past a threshold — receiving fewer than 75% ‘no’ votes — to be voted on this week in-person.

Gideon Smith, a plant taxonomist at Nelson Mandela University (NMU) in Gqeberha, South Africa, expects an extremely close vote for the ‘caffra’ amendment, which he and fellow NMU taxonomist Estrela Figueiredo submitted. To pass, the vote requires a 60% super-majority, but the outcome will depend on who attends the congress, as well as ‘institutional votes’ that allow herbaria such as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in London to allocate proxy votes to an attendee, says Smith.

“There is resistance against these proposals, the fear of throwing plant nomenclature into chaos,” Smith says. But he adds that the upshot of no longer requiring scientists to use a term that they find hugely offensive far outweighs the minimal practical consequences of the changes. “I cannot think of any simpler way to get rid of this racial slur.”

Kevin Thiele, a plant taxonomist at the Australia National University in Canberra, expects that, if his proposal to create a mechanism to remove offensive names is approved, a relatively small number of species names would change. It’s likely that the argument for stability in species names would be outweighed only in cases in which plants are named after “sufficiently egregious” individuals, he says.

One change Thiele would like to see is to a genus of flowering shrubs, most of which have yellow blooms and are found in Australia, called Hibbertia, with new species routinely discovered. They are named after George Hibbert, an eighteenth-century English merchant who profited from the slave trade and fought abolition. “There should be a way of dealing with cases like Hibbert,” he says.

Limited resources

Alexandre Antonelli, a Brazilian scientist and director of science at Kew, sympathizes with such concerns and would like to see a wider discussion of how to increase equity, diversity and inclusion in the field. But he worries about the practicalities and unintended consequences of changes to naming rules, such as who would judge changes or how disagreements would be arbitrated. Moreover, Antonelli argues that limited resources are better focused on cataloguing, studying and protecting biodiversity. “I wouldn’t be supportive of proposals that derail that process,” he says.

Some researchers have called for even bigger changes: an end to the practice of naming species after people1. But that doesn’t seem fair, says Freire-Fierro, and could rob researchers in the global south of the opportunity to name species they discover after local scientists and Indigenous leaders, or to raise funds for conservation.

Even if the two proposals being considered do not pass, Thiele and others say that the issues they’re attempting to address are not going to go away. Gillman, for instance, would like to see future botanical congresses consider replacing some existing plant names with longstanding names used by Indigenous groups. “It would be very cool if they manage to get something over the line,” he says of this week’s vote. “Change often happens incrementally.”