“The effect of a cultural bomb is to annihilate a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves.”

-Ngugi Wa Thiong’o [1]

This essay delves into a set of Palestinian artworks through a conceptual framework that questions the general use of media imagery of Palestinians as faces without names and people without a voice. It attempts to highlight Palestinian cultural production’s relationships with hegemonic ideologies, national and ethnic identities, self-determination under colonial occupation and ultimately the conflict-ridden landscape of not only Palestine but largely West Asia. To produce art from such contested sites is to constantly negotiate what is meant by resistance in art; and how as artists and viewers we can stand witness, position ourselves with the victims, while simultaneously imagining and creating ever newer structures of opposition to the status quo.

As the images of the ongoing genocide inundate our screens, many debates arise around the question of images and ways of looking. This genocide is unique in the fact of it’s consistent documentation by the people living right in the middle of it all. Images are important because they are evidentiary documents; they are supposed to point towards a materiality of truth that no discourse from any side of the ideological spectrum can embody. There are debates, however, about the ways in which we consume these images; the excess of this imagery also runs the risk of desensitizing us towards the gravity of the mass destruction happening right in front of our eyes. It is in this regard that art can save us; as in its reinterpretation of the visual world it inherits, it shows us how to really look.

There are physical bombs and there are cultural bombs; the former is no more material than the latter. While the physical bombs hold the capacity to destroy whatever land exists for the Palestinians; the cultural bomb holds the capacity to destroy the ability of the Palestinians to imagine their own land. The power to imagine an alternate reality is the driving force of any struggle against injustice.

To appreciate the persistence of so many Palestinians to envision an alternate visuality for themselves, we must first understand the cultural politics of war and the concept of war as culture itself [2]. Why do we need to look at artworks by Palestinian artists? How does the experience of looking at their interpretations of the genocide differ from simply consuming the images of the war-torn city? What are the implications of viewing this genocide in today’s media society?

The act of recording through media “converts every challenge to thinking universally and diagnosing violations of universal principles into ‘scenarios’ of rules and violations, rights and infringements” as observed by Soumyabrata Choudhary in his book ‘Thoughts on Gaza far from Gaza’. The cutting-edge technological advancement of media society means that the loss of civilian life and property resulting from each military action can be recorded to its very last detail. But this objectivity that media evidence enables also reveals, for this very reason, the extent to which truth is manipulable due to the sophistication of today’s technical apparatuses. This relativisation of truth claims in today’s media society immobilizes us; so that the images we encounter daily with our limited attention spans carry traces of truth but do not allow any real cognitive space to understand the gravity of the events they claim to depict [3]. Choudhary also notes the automatism of media apparatuses that record this devastating misery in real time- for which “the human being is only a trigger, or even more ironically, a medium.”

Artistic practices from the region in such a time must be understood in these contexts as interventions in the protocols of receiving and reading images that we inherit from this media society, and reveals above all the creative force of a people refusing to accept their loss at the hands of the genocidal state of Israel as the ultimate destiny.

The ‘sovereign right to kill’ that Israel has accorded to itself traces its genealogy back to slavery and colonial imperialism, where colonizers could act with impunity and without rules [4]. The self-justificatory force of any imperial governance is first and foremost aesthetic, meaning a priori. We see something immediate as real and accord to it the status of ‘reality’. Visuality’s politics lies in making the separation between the autocrat and the ruled so permanent that it is beyond questioning. It heavily relies on the lack of authority of the civilian population to imagine an alternate reality [5].

News media from sites of imperial governance such as the U.S also lament the long-drawn ‘war’, but their weaponisation of the ‘network form of war’ and intensification of military-industrial visuality only perpetuates it indefinitely. The ‘pinnacle’ of these wars instigated by the American military-industrial complex is understood to be forever impending, a ‘nuclear’ disaster that is always in an incomprehensible futurity but a possibility nonetheless, and which must, through all means necessary, be averted. This ‘fabulously textual’ status of nuclear war generated the very status of the old world’s culture, civilisation, and ‘reality’.

The imperial colonizers thus engage in a pre-emptive warfare, calling it and visualising it as a ‘global war on terror’. ‘Image wars’ are central to this doctrine, which imagine decisively defeating its enemies in battle and ideology. Thus if one sifts through the varieties of imageries that the American invasion into Iraq produced, from ‘surveillance maps’ and ‘selfies with inhabitants’ to ‘population surveys’, to understand the violence of visuality is to make note of how amongst the image of an American soldier giving thumbs up gesture while standing next to an Iraqi girl, and the same soldier repeating her gesture next to an Iraqi corpse, both scenes represent violence.

Non-existent images of ‘headless Israeli babies’ went viral on our screens; a digital image in its very being wants to be circulated by all means necessary. What virality of such images generates is not the excess that embodies a sincere attempt at documenting a ‘truth’, but an excess that ensures that no single instance could be decisive. Which explains the innumerable procedural attempts by neo-liberal organisations such as the ICJ, United Nations, to bring Israeli war crimes to justice but always falling short of the decisive act of stopping the genocide.

The very justification of the invasion of Palestine, centered on such alleged violent acts by Palestinians on October 7, survived the clear demonstrations that there were none. That is the power of visuality and virality. In the hands of authority, it claims an evidentiary status that can long survive proof that it is false.

On the other hand, one is confronted with images of advertisements of Israeli real-estate agencies that have swiftly moved to declare the debris of Gaza as ‘inhabitable land’. It is in this context that we study the artworks of Ala Albaba, John Halaka, Malak Mattar, Abdel Rahman al-Muzayen, Sliman Mansour and learn how these artists are expressing about the life and resistance in their ‘homeland’.

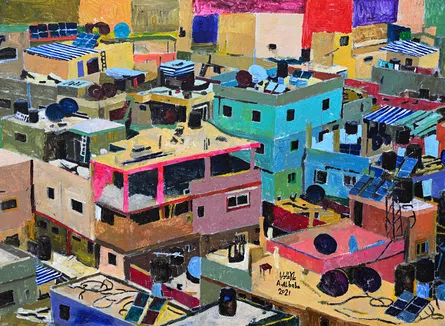

Image: Ala Albaba: The Camp #21, 2021

Starting with the painting ‘The Camp #21’ by Ala Albaba we see, a detailed rendering of a refugee camp in Palestine. The buildings are all coloured in bright hues, with flat strokes and simple brushwork; the complexity of the painting instead lies in the details that the artist has managed to capture of what life must be like in the refugee camp. One must note that while the images from popular news sources that are inundated on our screens of war-torn Palestine show people in refugee camps scrambling for food, make-shift houses built on debris, wailing women and children; this painting and the general representation of Palestine by Palestinian artists is one of a life of dignity and hope. It reminds us of videos of children, young inhabitants in refugee camps who strive for collective resilience and joy by performing acrobatics, dance sequences, distributing food and toys, and jumping from one building to another.

While photos of the camps from mainstream media show the cramped spaces as health hazards and signifying lack of resources, this painting shows in those same cramped spaces dignity and abundance and solidarity. The colours of the windows stand in stark contrast with the building’s outer appearance, as the black void-like windows might signify abandoned homes and other buildings that might have fallen out of use. They do, however, look functional; there are satellite dishes, solar panels, clothes drying and other household equipment that animate everyday life. The artist seems to have made this painting looking out from a similar building. The fact that Ala Albaba chose to paint a wide expanse of settlements to denote a population without showing the figures of people who might be living inside them, reveals the constant anxiety and horror that underlies life in Palestine. The absence of people marks the constant displacement of the population, and the everyday household items of utility might speak of the individual, mundane lives that the inhabitants lead.

Image Source: “When Is a House a Home?” The re-signification of civilian spaces into military targets. / Israel Defense Forces blog (2014) Cited in https://thefunambulist.net/magazine/17-weaponized-infrastructure/37293-2

It is important to remember that Israel’s settler colonial apparatus is constructed on the idea of the Palestinian population as essentially ‘nomadic’, thereby claiming the sovereign right to destroy their homes. It comes as no surprise then, to see infographics released by the IDF asking questions like ‘when is a house a home?’

The violence of its visuality lies in its rendering of the different rooms (sites of intimacies and subjective formation for the Palestinian families) as ‘operation rooms’, ‘weapon storage rooms’, ‘commander centers’, etc. Their denial of the right to life is by turning the infrastructures that generally hold familial life into sites of insurgency and ‘conspiracy’ against the State, thereby denying the Palestinians any narrative of subjectivity. The frameworks that the army deploys come from their architectural and territorial visions in which they can declare any moving body as a ‘non-civilian’. Ala Albaba’s and John Halaka’s respective engagements with the images of homes and other intergenerational architectural places and their memories try visualize the tensions between the emotional presence and physical absence of populations whose cultures have been devastated by the violent intrusions of settler colonialism.

Image: John Halaka: Memories of Memories, 2023

However empty the homes depicted in the works of these two artists might seem, they are a refusal to partake in the destruction of the idea of a Palestinian home. This repeated invocation of the homeland and the right to return is a recurrent motif in Palestinian art for example, the use of the symbol of the key,

A symbol that signifies another kind of ‘return’ is the Dove, which when used in Malak Mattar’s paintings offers a clear departure from its appropriation by neoliberal institutions proclaiming themselves as ‘harbingers of peace’, and its reclamation in the hands of a young girl.

Image: Two Gazan Girls Dreaming of Peace, Malak Mattar

In ‘Two Gazan Girls Dreaming of Peace’, Malak Mattar shows two girls looking onwards at the viewer, with a glint in their eyes, as if welcoming the viewer to join in their embrace. They are seen holding a white dove, symbolizing peace in general. If one follows the genealogy of the figuration of the dove one can trace the roots of its symbolization in religious texts of the region. According to biblical lore and its counterparts in other religious texts, a dove was released by Noah after ‘the flood’ to find land, and when it came back carrying a freshly plucked olive leaf. It’s return denoted a sign of life after ‘the flood’. The dove as a symbol was subsequently appropriated by different organizations. Most notably, the United Nations which itself failed in its duty towards the Palestinian people in its inability to uphold the very principles it claims to have been founded upon. The dove in the painting seems to have ‘returned’ and perched on the hands of the two women, seemingly content in its rightful place; it is not in motion but rested and at peace. The painting marks perhaps a ‘return’ of the dove, denoting signs of life not in the war-mongering societies of the West where it was caged in meaningless logos and appropriations, but instead finding traces of life in the resilient social relations and bonds that have ensured the Palestinian people’s survival against all odds.

The halos around the women’s heads, usually mark presence of divinity, but here they note the people’s everyday resilience as god-like. The warm red hues of the background evoke a feeling of the calm and warmth that prevails after a long-standing struggle, facing their despair with a calm confidence in justice in the future. Malak Mattar also talk about love in her paintings. The painting ‘You and I’ is based on the poem by with the same title by “the Palestinian Poet … Mourid Barghouti, Dedicated to His Late Wife Writer Radwa Ashour, my painting is a tribute to Mourid Barghouti and Radwa Ashour who made us live the beauty of love in Palestine and the pain of exile.[6]”

Image: You and I, Malak Matar

It presents two people embracing each other. The decoration on the clothes and the pose in which they are holding each other is reminiscent of the painting ‘The Kiss’ by Gustav Klimt. The artist’s repetitive attempts at re-interpreting western traditions and canonical styles into her own paintings must be noted because they connote a Palestinian artist’s attempt to find her own voice in an art milieu that is dominated by artists from the West. The embrace between both the people seems so intense that the separation between the two bodies, or ‘You and I’, is rendered invisible. This work, along with Malak Mattar’s ‘Two Gazan Girls Dreaming of Peace’, is in stark contrast with the artist’s rendering of the war in Gaza. There are stylistic affinities between the two sets of paintings, as they both make use of flat brushstrokes, curved figures, solid application of colours; but the artist’s diversity of subject-matter speaks of the multiple voices in which the Palestinians speak to the world – anger as well as celebration, despair as well as hope, in movement but also rooted.

Abdel Rahman al-Muzayen’s figuration of Palestinian women raising their arms and flags in resistance is another image that speaks of Palestinian agency, subjectivity, resilience, communal strength. The stark, linear edges of their clothes and bodies are almost masculine and reveal a stoicism and will to persevere in their struggle. The women’s clothes show olive leaves and trees as well as palm trees, symbolizing the Palestinian landscape that finds refuge in them rather than them finding refuge in the landscape. Their bodies are in movement, but also static and rooted to the ground on which they stand. The figures have a solidity and iconic statue-like disposition which is reminiscent of ancient Egyptian art’s figuration; perhaps the artist is using that tradition of figuration to assert the Arabic identity and its historical legacy over the cultural and claimed civilisational hegemony of the west. The flags that they wave are churning and revolving like waves of a sea invoking in this case, the Palestinian idea of sumud, a word that connotes the condition of searching for a stoic posture in the face of disaster.

This work shows a Palestinian woman hurling a sling shot, the sling of which seems to merge into the embroidered cloth that she is wearing. The stone in the sling she is about to hurl, however, shows a small image of a gun, perhaps denoting the methods of Palestinian resistance. The power of intifada was, as it asserts, in its ordinariness. The woman’s dress also shows more women soldiers in a similar stance, aiming their sling shots into the distance, with a resolute gaze. The heavy assertion of traditional Arabic identity is also stressed through the embroidered clothes and their patterns. The drawing is done in such a way that the women, their hair, garments, the larger landscape, etc are not separate pictorial elements but a well-oiled machinery in which they all constitute each other and envision the same future.

The action of hurling a sling shot must be seen in the context of the image representing a long history of revolt by colonized populations against settler-colonial projects across the world. Slingshots and stone-throwing reject constant victimization, asserting instead the authority of resistance instead. They represent powerful autonomy in the responsibility to resist and to remain actively antagonistic.

Image: Abdel Rahman Al Muzayen, Palestine Series, 2000

If one sees the paintings ‘Revolution Was the Beginning’ by Mansour and Malak Mattar’s ‘Gaza’, the long expanses of landscape and multiple timelines on one single surface of the painting show the Palestinian struggle and Nakba as a long history of defeats but also the refusal to accept it as a final predicament. It is history painting in the truest sense of the word.

Image: Sliman Mansour (Palestine), Revolution Was the Beginning, 2016.

Sliman Mansour’s ‘Revolution Was the Beginning’ is a painted landscape showing different scenes from the Palestinian life. On the extreme right, one can see refugee camps over which a dark cloudy sky looms. Two Palestinian women look on as younger groups of people and families march onwards in the hope for a better future; and the gloomy dark sky with a vulture symbolizing death transforms into a bright sun in which a dove flies in arms with a young girl. The three figures in the segment are holding three different symbols of Palestinian resistance; the boy holding a gun with an olive leaf, a woman holding a key symbolizing an imminent return of the Palestinian people to their homeland after the mass exodus, and the woman in front holding a brush and a pen symbolizing the intellectual, artistic lineages of the Palestinian struggle.

The two figures in the centre are beautifully painted, with their clothes showing different snippets of the Palestinian landscape. The man’s robe shows the rows of olive trees and a view of the al-Aqsa mosque in the old city of Jerusalem located near the man’s chest; representing the cultural, and geographic symbols at the heart of the Palestinian identity. The man and woman look on as two figures seem imprisoned behind bars, a young resistance fighter leaps over a burning tire and a woman aids a fallen man. Towards the far left, a man and a woman collectively carry forward the Palestinian flag, with their keffiyeh and the flag waving in the wind. The composition of the work heavily relies on narration, consistently showing the movement of the Palestinian people from distress and violence towards peace and an egalitarian society. This is done by a repetitive assertion of the Palestinian cultural symbols and identity at the heart of their resistance. By invoking words like ‘beginning’ in the title and the old Jerusalem site, the artist is stressing on the struggle as a historical one in which resistance has been a constant road towards emancipation rather than singular events or dates in time.

The Painting ‘Gaza’ by Malak Mattar is a chaotic rendering of the different forms of violence that have been inflicted on the Palestinian people. On the far right on top, one can see lines of men stripped naked with their hands tied on their back, a never-ending line that is juxtaposed with debris of buildings destroyed during the genocide. As we look below, an IDF soldier seems to target a graffiti artist who seems to be speaking to the soldier through the medium of graffiti, saying that the atrocities committed by the likes of him will haunt them forever. Further below are carcasses, bodies of lives taken by the military forces, and a hand that seems to be pulling up a woman trying to escape from the scene. On the other side, one can see the bombing of the city as the skies are lit up by bombs instead of stars, buildings like churches, houses, and other community centres that await their destruction. As we go further below, a wrecked car, a bloodied press jacket, a child’s severed body, and a man wailing while holding what might be remnants of a loved one. In the middle, however, is a horse-drawn cart on which a person is carrying their belongings like a rolled-up mattress, chairs, tables, and all the other items that might’ve once animated their home. The artist’s own experiences of displacement and having to leave behind her community must have contributed to her rendering of the figure of the refugee rushing away from her hometown ravaged by the military forces. The mountain of belongings on the cart seem to fall all over the space so that they become one with the debris and the violent cacophony in the background; speaking of the impossibility of reconstructing a peaceful life after having witnessed the horrors in her own city committed on her own people.

One must note, from an interview in which she spoke to Tings Chak [8], that the artist insists that art is not supposed to be comforting, it is supposed to disturb because the conditions in which it was made were such. The artist has not shied away from, or aestheticized, the cruel violence imposed on her people; which is why the painting does not look for any ‘beauty’ or ‘redemption’ but lays bare the inhumanity and moral depravity that is at the heart of the world order. One can say that the destruction of the city and the people within it is a part of her art; and images of the war will always inform and follow how she organizes her life ‘elsewhere’. The composition and disembodied representation of people and the city evokes a similar organization of space as seen in Picasso’s Guernica, another anti-war painting, which is telling of how the artist has re-interpreted canonical artworks to represent her people’s lived realities.

Palestinian artists are constantly reinterpreting and thus re-energising what is considered to be canonical from a marginal lens. The position from which they speak is “one of knowledge and authoritative learning, but also from the position of people whose message of Resistance and contestation is the historical result of subjugation”, as described by Edward Said [9]. Therefore, a painting, in its very act, is a process of deconstruction of inherited frameworks of looking. He speaks in this regard of cultural activities from subjugated peoples as:

[C]hoosing to focus on rhetoric, ideas, and language rather than upon history tout court, preferring to analyze the verbal symptoms of power rather than its brute exercise, its processes and tactics rather than its sources, its intellectual methods and enunciative techniques rather than its morality — to deconstruct rather than to destroy [10].

The question, ultimately, for us viewers who encounter such devastating images of genocide in this media society from this inarticulable distance, is how we can rejoin experience and culture. The question is a matter of knowing that what we see invariably informs how we see. It is to constantly remind oneself that the relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.

Artworks and cultural activities in the larger sense are not finished objects, unlike the photographs and antiquities stored in imperialist archives. Israel’s ‘onto-epistemological’ attack on the Palestinian world was orchestrated through a combined use of military technologies and technologies of museums and archives, which organized the world according to European taxonomies. Every artwork coming from Palestinian experience is thus a refutation of the limits and categories that these archives impose by refusing to imagine the end of poetry.

What I Can’t Imagine

When the Earth, after a pileup of planets,

is swallowed by a black hole

and neither man nor bird remains

and all the ghazelles and trees are gone

and all the countries, and their invaders, too…

When the sun is nothing

but the cinders of a once-great blaze

and even history is over,

there will be no one left to tell the tale

or be shocked by the frightful finale

of our planet and our kind

I can imagine that ending

I can even surrender to it

but what I can’t imagine

is that it will also be

the end of poetry

-Najwan Darwish

Notes

[1] Wa Thiong’o, Ngũgĩ. “Decolonising the mind.” Diogenes 46, no. 184 (1998): 101-104.

[2] Choudhury, Soumyabrata . 2024. Thoughts of Gaza far from Gaza. New Delhi: Navayana.

[3] Ibid

[4] Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2011. The Right to Look :A Counterhistory of Visuality. Duke University Press.

[5] “Imagining Palestinian Futures beyond Colonial Monumentality – the FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE.” 2021. Thefunambulist.net. August 31, 2021. https://thefunambulist.net/magazine/against-genocide/imagining-palestinian-futures-beyond-colonial-monumentality.

[6] Malak Mattar on the inspiration behind the painting, ‘You and I’ https://www.facebook.com/MalakMattarArtist/posts/you-and-i-a-poem-by-palestinian-poet-who-passed-away-today-mourid-barghouti-dedi/1784539988367956/

[7] Chak, Tings. I Don’t Create for Institutions; I Create for My People Art Bulletin No. 1. March 2024. https://thetricontinental.org/triconart-bulletin-march-2024/

[8] Said, Edward W. 1994. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage Books,

[9] Ibid

[10] Abu-Zeid, Kareem James , and Omar Sakr. 2016. 6 Poems by Najwan Darwish. Translations Cordite Poetry Review, May. http://cordite.org.au/translations/abu-zeid-darwish-sakr/.

|

Vanshika Babbar is a visual artist and pursued her Masters in Visual Arts from Ambedkar University, Delhi and finished her Bachelor’s in Fine Arts from MS University, Baroda. |