Gestural marks move across space as if alive, taking the forms of tree branches, talismans, and obscure scripts. Iridescent layers of pigment overlap each other as they move toward the rounded edges of a granite plane. What can these paintings—by Benjamin Herndon and Adie Russell, currently on view at Kingston’s Headstone Gallery—tell us about the nature of the self? How do light, color, and material choices mirror one’s inner knowledge? These are the questions that arise from Herndon and Russell’s paintings in this exhibition, which will be on view until June 1.

Kingston-based artist Adie Russell undertakes profound investigations into the nature of landscape in this body of work, drawing on the compositional tropes of landscape to activate the viewer’s sense of how they’re reading a space. At the same time, the elements that appear in these abstract landscapes take on their own vibrant character and presence.

<a href="https://media2.chronogram.com/chronogram/imager/u/original/23553304/4_solidarity_2025.webp" data-caption="Solidarity, Adie Russell, 2025

” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

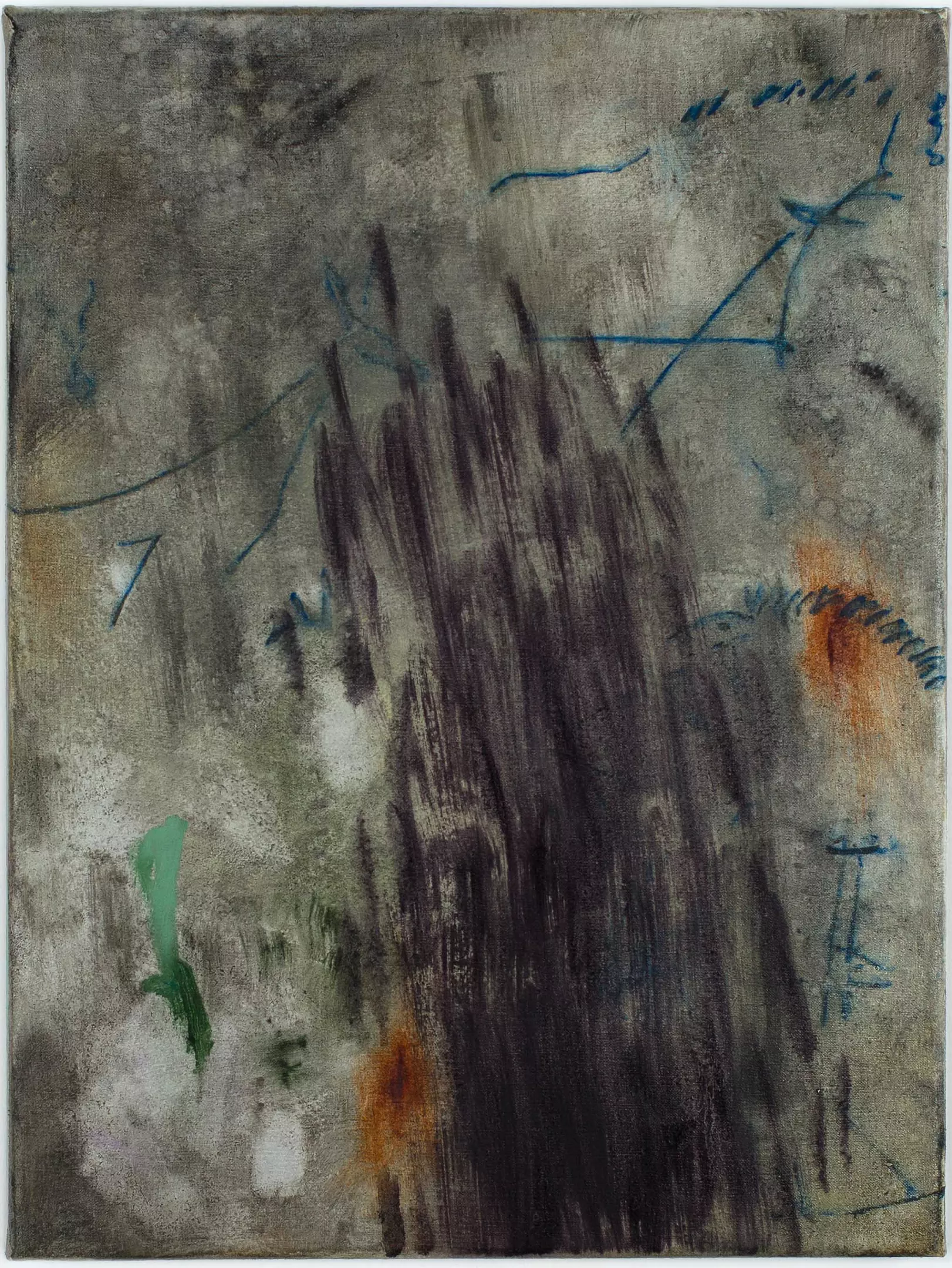

Solidarity, Adie Russell, 2025

In Solidarity, blue, green, and black marks dance over a densely layered gray-white background (what Russell terms “color as atmosphere, or air”). Russell made this piece in conversation with the prehistoric painters of the Chauvet Caves in France; these 32,000-year-old paintings were created in caves later inhabited by bears, who rubbed up against and scratched the paintings’ surfaces. With Solidarity, Russell taps into a sense of intimacy with the people and animals who made those ancient paintings, and the decentralizing of human culture that accompanies this intimacy.

Dwelling in close proximity on Headstone’s wall is Herndon’s piece one and the same, which carries the themes of intimacy and presence and pops them into three dimensions. Made from metal oxide pigments and graphite on Westerly pink granite, one and the same is an object-painting that one can imagine holding in a palm. The piece’s achingly precise layer of iridescent pigment invites the viewer to dwell on the surface, discovering how much substance—narrative, mystery—a surface can contain.

<a href="https://media2.chronogram.com/chronogram/imager/u/original/23553305/one_and_the_same_pl.webp" data-caption="one and the same, Benjamin Herndon, metal oxide pigmnts and graphite on Westerly pink granite, 2024-2025

” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

one and the same, Benjamin Herndon, metal oxide pigmnts and graphite on Westerly pink granite, 2024-2025

Herndon, who is lives and works in Providence, Rhode Island, has a longstanding practice of using graphite and other mineral pigments that both absorb and reflect light. Several of Herndon’s pieces are tonal black-and-gray works in graphite and oil paint; in their vast quiet and spaciousness, works like the big and small of it and bivalence draw on the traditions of minimalist abstract painting while suggesting the contours of deep time and outer space. The effect is an intense, almost distilled awareness of presence.

While Herndon’s paintings are concentrated and condensed, Russell’s works in the show are often expansive, spooling out into their own complex territories. The biggest piece in “More Than Any Mirror” is Russell’s The Poet’s Garden. I found that, perhaps more than any other painting in the exhibition, this painting made me think about perspective—where the body is in space, how the eyes move across and through forms. A word that Russell invoked in talking about this piece is “flickering,” as in the flickering of light on leaves in a forest, the movement of birds through trees, the motion of branches in the wind. This work, and others, show how painting can revivify our understanding of landscape—what’s “out there”—and our understanding of our own perspectives within that landscape, and within the place we find ourselves.