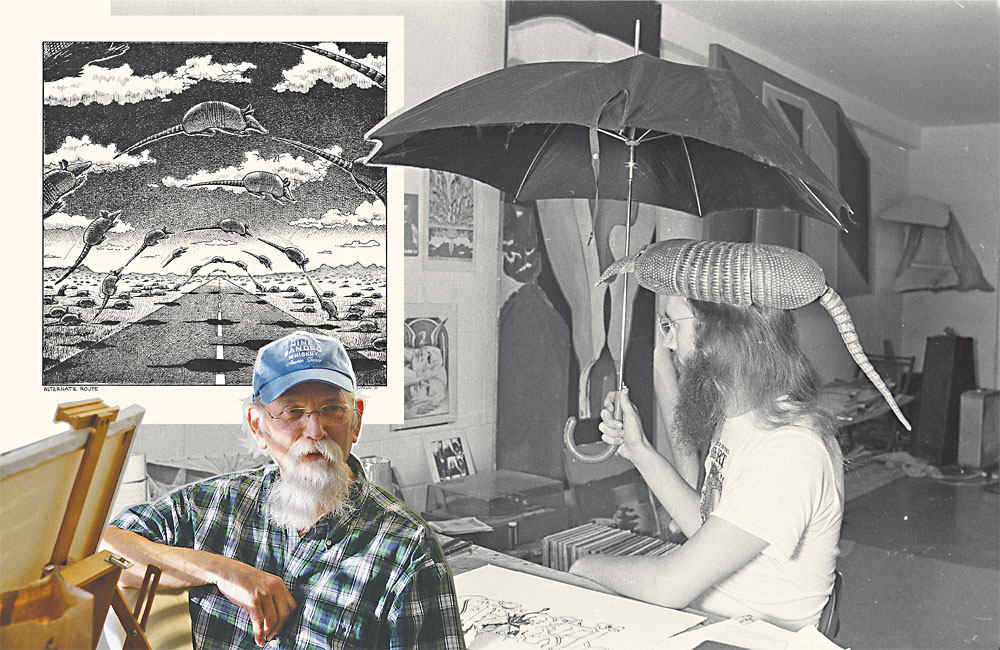

Jim Franklin, now and then (at Armadillo World Headquarters in 1971). Top left: “Alternate Route” by Jim Franklin, 1971. (Art / photos courtesy of the Austin Museum of Popular Culture)

Though he’s perhaps the most cartoonish character of all Austin’s hippie-era poster visionaries, Jim Franklin brought museum-quality artistry to the concert promotions of the Vulcan Gas Company, Armadillo World Headquarters, and Ritz Theater, while proliferating the nine-banded armadillo as a symbol of Austin’s spirit. Descending locally in 1967, after a childhood in La Marque, Texas, and a spell in San Francisco, Franklin’s wondrous concepts and detailed portraiture helped cement a Fillmore-like association between art and live music in Austin. A familiar sight to concertgoers for his eccentric master-of-ceremonies appearances, Franklin is also a songwriter and painter of international renown. The King of the Freaks is now 80, still making art and often sought out by young musicians who want a firsthand dose of “709” vibes. On his appointment to the Austin Music Hall of Fame, Franklin cracked: “In other words they’re gonna put me out in the hallway, they’re not going to let me into the room.”

Austin Chronicle: You actually lived in the Vulcan Gas Company and the Armadillo while making their posters, which gives a very literal meaning to artist-in-residence. Was that a necessity of survival or a way to ingrain yourself into an artistic study of the venue?

Jim Franklin: The thing that was most important to me was the studio space. I started off with some of the old warehouses along Fourth Street. They were big, they had character, and they were available next-to-free, which was important because I’ve always been “self-unemployed.” Living at the Vulcan and Armadillo gave me space to work, and the money I would have spent on rent, I could spend on paint.

On being the guy who made Austin synonymous with armadillos: “I think it’s a good thing, because I turned [Austin] on to a remarkable animal that’s not a cute, fluffy thing you can cuddle up to.”

AC: Tell us about your first armadillo.

JF: My first armadillo drawing was for a benefit for some guys who’d been busted for pot and they were in the county jail. It was in ’67 or ’68 in that park across from the county courthouse. The armadillos were inspired by a hunting trip with my father when I was about 10 years old. He was stealthy about creeping up on deer and of course I was stepping on sticks and making noise. So he let me go on my own and I saw an armadillo. I slipped under this barbed wire fence to get close to it and it was digging. When I was about 5 feet away, it turned around and walked between my legs, just minding its own business, head down. I thought, “Wow, that looks like a miniature dinosaur – and it walked between my legs,” which made a big impression on me. Decades later, I’m searching my mind for a poster image, and I thought about this prehistoric animal in contemporary time and realized that’s a perfect setup for surrealism.

AC: Do you feel responsible for the popularity of armadillos in Austin?

JF: Yeah, because no one was doing that before me. I think it’s a good thing, because I turned them on to a remarkable animal that’s not a cute, fluffy thing you can cuddle up to. People are still picking up on the armadillo phenomenon. I recently looked up how many armadillo businesses are in Austin and it was just page after page after page. Like me, I think Austin has been attracted to it because it’s not a typical animal.

AC: Where do you see yourself in Austin’s cultural legacy?

JF: I’m a professional outsider. My first two heroes in art were Da Vinci and Michelangelo. I didn’t copy their painting but I copied their imagery and influence. My art was based on what I could discover and not what I’d already seen. I did not want to emulate. There’s this incredible universe we’re living in; why would we copy stuff that’s already popular when there’s so many subjects that are open to interpretation?

AC: You have a practice called “Les Yeux Fermés,” which refers to painting with your eyes closed.

JF: It was my way of entertaining myself. How can I surprise my own eye? The answer was so simple: Close your eyes, dummy! It’s been said that all art is self-portrait … so I closed my eyes and drew a self-portrait. I thought it was all going to be scribbled, but I said, damn, I’ve got everything in there – even the highlights of my pupils, but the placements are off – which gives it that distortion that I love in art.

AC: Were you blindfolded?

JF: No. I’m honest – I closed my eyes. I’m not gonna cheat! The whole point is to surprise myself. It’s not like I’m having a contest with myself. I’ve never peeked.