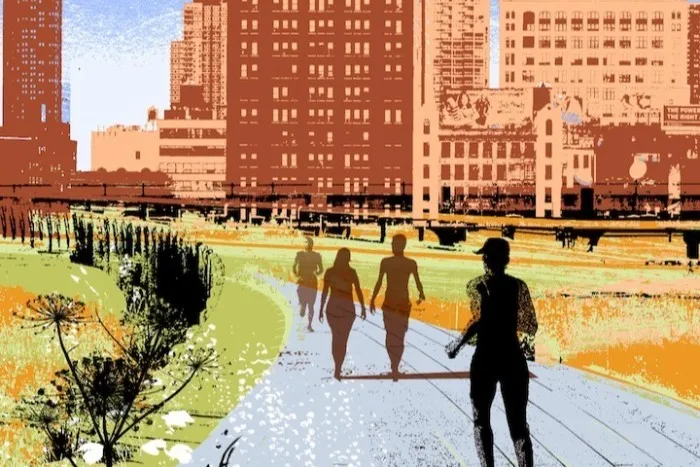

This article is part of FT Globetrotter’s guide to New York

No matter how aggressively MoMA expands — and by now it’s consumed nearly an entire midtown block — the museum can still only display a meagre slice of its possessions at any given time. Rather than commit to a single ossified version of art history, curators keep the permanent collection in slow, ever-changing rotation.

A few crowd-drawing perennials — Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” and Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”, for instance — never budge, but periodically one Rauschenberg displaces another, or a whole flock of Helen Frankenthalers may magically appear. For this tour, I’ve picked some longish-term residents and, while I can’t guarantee that any one work will be on view when readers pay their visit, my idiosyncratic list hints at the museum’s dizzying range. Among the innumerable paths one could pick through the multiplicity of modernisms — deadpan cool, macho Expressionism, conceptual gamesmanship, and so on — I’ve chosen one that speaks to a sensibility (mine) rather than represent a school. The result is a collection that shies away from moderation and instead tends towards the gross, the loud and the irrepressibly over the top.

1. ‘Hide and Seek’, 1940–42, by Pavel Tchelitchew (fifth-floor hallway)

This is one of those paintings people either love or love to hate. I find it one of the most hideous things an artist ever dreamed up, and yet it beguiles me, too. The melange of rainbow hues — which a critic once described as “pus-and-ketchup” — takes hold of the eye and won’t let go, demanding that you notice when the central tree sprouts fingers and toes, how branches morph into veins and arteries, and that the skulls of babies multiply and dematerialise at the same time. The critic and curator Robert Storr coined the term “retinal hysteria” to describe this kind of calculated offence to good taste. Enjoy.

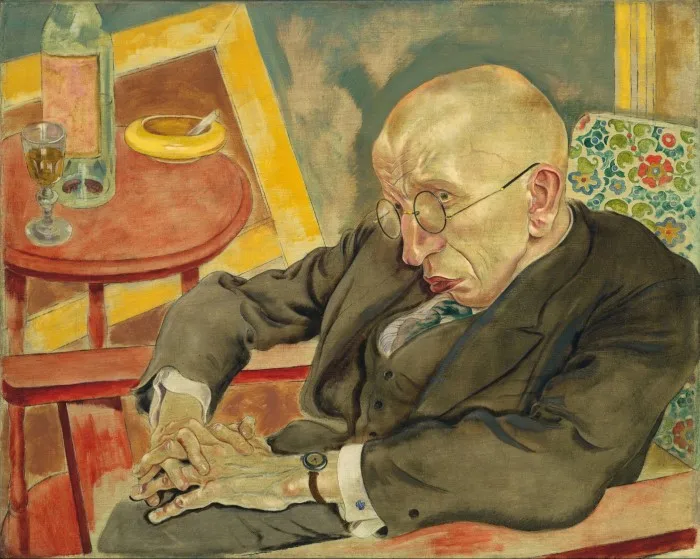

2. ‘The Poet Max Herrmann-Neisse’, 1927, by George Grosz (Room 514)

Grosz channelled his Weimar-era rage and disgust into a bleakly objective portrait of a close friend. He spared neither viewer nor subject, insisting we gaze on crude reality rather than prettified fantasy. Veins bulge on the brow of the man’s bald head. His fingers lie gnarled in his lap like some kind of woody growth. Yet genuine sympathy emerges amid the harshness, thanks to Herrmann—Neisse’s intimacy with Grosz. Sitter and artist shared leftist politics, an acid sense of humour and a dandified propriety, all of which come through the surface grotesquerie.

3. ‘Girl before a Mirror’, 1932, by Pablo Picasso (Room 517)

Of all the Picassos in MoMA’s stockpile, “Girl before a Mirror” has enchanted me for as long as I can remember. I first glimpsed it in a well-thumbed book of reproductions on my parents’ bookshelf, back when I identified with the dewy profile on the left, blemishless and blithe. Now I feel closer to the girl’s more shadowed future reflection. Even so, the painting dazzles me every time. Neither Blue Period nor Pink, skirting both Analytic and Synthetic Cubism — and not really Surrealist, either — it’s a uniquely radiant display of beauty in a long career.

4 “The Migration Series”, 1940–41, Jacob Lawrence, (Room 520)

Lawrence was only 23 when he created the 60-panel masterpiece that launched his reputation and still stands as a triumph of visual and moral authority. The series tells the story of the two million Black Americans who headed northwards from the south and often wound up trading one form of suffering for another. It’s a tale told in stripped-down, syncopated rhythms of form and colour. The Downtown Gallery’s 1941 exhibition of the whole set marked the first time a major New York gallery represented a Black artist. MoMA immediately acquired half the panels (the Phillips Collection in Washington took the rest). Even in its truncated form, the series bundles truth, ruthlessness, and empathy into an overpowering saga.

5. ‘Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair’, 1940, by Frida Kahlo (Room 517)

Whenever I look at a Kahlo self-portrait, I come down with a severe case of ambivalence, beguiled by her intensity and put off by her self-dramatising persona and repetitive exotica. This, though, is a Frida I understand: severe, defiant, unsentimental and undaunted. She has traded in her voluminous skirts and embroidered tops for a baggy men’s suit. Instead of threading brilliant flora through a carefully composed hair-do, she’s hacked off her tresses and left them wriggling on the floor. The words to a popular Mexican song run across the top of the frame: “Now that you are without hair, I don’t love you any more.” Her expression delivers the silent retort: “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

6. ‘Object’, 1936, by Meret Oppenheim (Room 517)

On a mythic afternoon in 1936, Picasso and his paramour, the artist Dora Maar, were having drinks with Oppenheim at the Café de Flore when they admired her fur-covered bracelet. The young Surrealist mused that anything could be transfigured with the addition of a pelt. She soon proved that theory by dressing a cheap porcelain teacup, saucer and spoon in the skin of a gazelle. Her eccentric creation travelled from Paris to the US, where it galvanised the press and provoked viewers into spasms of “rage, laughter disgust or delight”, according to MoMA’s then director, Alfred H Barr. Nearly 90 years later, it’s still pushing the same buttons.

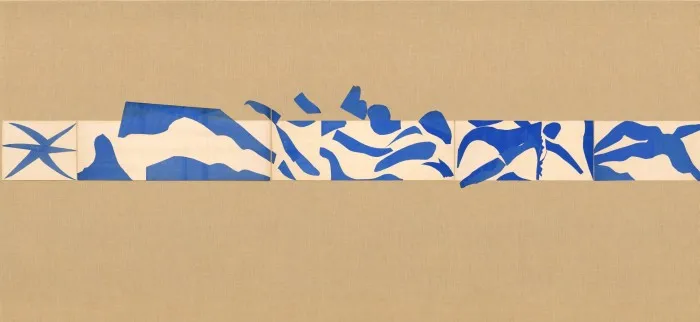

7. ‘The Swimming Pool’, 1952, by Henri Matisse (Room 406)

Having to select just one Matisse from MoMA’s spectacular trove was a conundrum. Should I pick “The Back”, the quartet of reliefs in which he gradually deconstructs a woman’s rear into interlocking abstract rectangles? How about “The Piano Lesson” or the even more obvious “Dance (I)”? In the end, I went for the exuberant, wraparound, site-specific environment that Matisse lavished on his ageing self. Though he enjoyed observing graceful divers at the public pool in Cannes, he couldn’t stand the heat. So he decided to fashion his own contemplative indoor version out of white paper and populate it with cut-out sea creatures and swimmers painted a cool ultramarine. MoMA’s dedicated gallery, which reproduces the installation as it was in Matisse’s home, offers a moment of startling serenity amid the throngs.

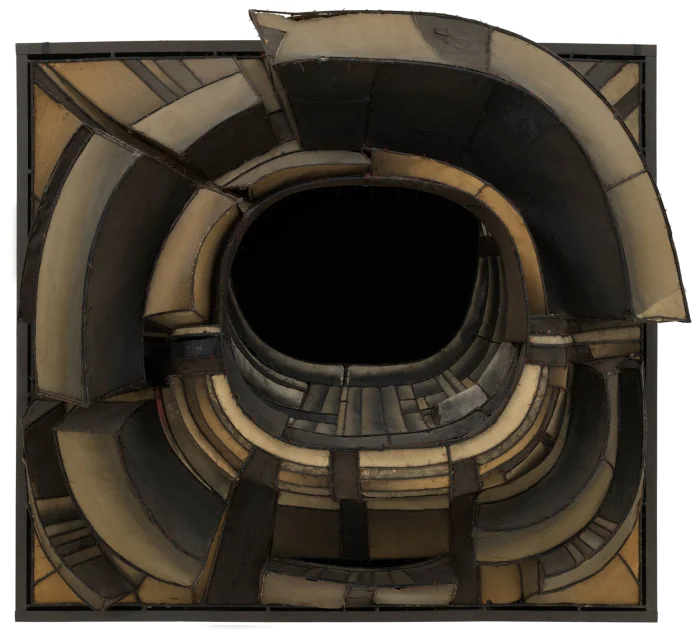

8. ‘Untitled’, 1961, by Lee Bontecou (Room 408)

A work of leathery texture, thick seams and impenetrable depths, Bontecou’s colossal early relief evokes a vast range of voids: an eyeless socket, a hungry maw, an extinct volcano, a dead TV screen. And that’s only an abbreviated list of its raging allusions. Bontecou’s sculptures don’t look like much in reproduction, which flattens protrusions, reduces scale and softens drama, but to see this one in person is to come face to face with a creature of menacing splendour.

9. “F-111”, 1964—5, by James Rosenquist (Room 418)

Rosenquist’s eruption of joyous vulgarity is tinged with an oddly bright and shiny form of pessimism. This 86-foot multi-panel canvas wraps around an entire gallery, enclosing viewers in its gaudy grip. Rosenquist, who trained as a billboard painter, seduced the public with a slick mix of bold graphics, candy colours, and jaunty Americana borrowed from glossy magazines. Despite its perkiness, this is a dark painting: the title (and one of the images) refers to the fighter-bomber designed to wreak havoc in Vietnam. The threat of nuclear apocalypse also lurks in the spectacle, ready to extinguish every hint of cheer.

10. ‘Cow’, 1966, by Andy Warhol (ground-floor lobby)

I almost missed this impish treasure as I pushed through the revolving doors on to West 53rd Street. Warhol’s superstars, including the soup cans and “Gold Marilyn Monroe”, occupy galleries upstairs, but pause for a moment on the way out for a mind-altering double-height field of pink cow heads staring placidly from their bright yellow pasture. Here’s Andy at his most endearingly lurid and playfully direct. What is art, he asks — and answers the question: whatever covers the walls.

Which artworks do you always head for in MoMA? Tell us in the comments below. And follow FT Globetrotter on Instagram at @FTGlobetrotter

Cities with the FT

FT Globetrotter, our insider guides to some of the world’s greatest cities, offers expert advice on eating and drinking, exercise, art and culture — and much more

Find us in New York, Copenhagen, London, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Paris, Rome, Frankfurt, Singapore, Miami, Toronto, Madrid, Melbourne, Zurich, Milan and Vancouver