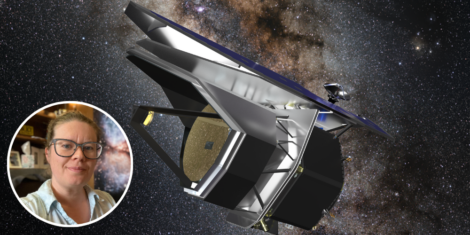

photo by: University of Kansas

KU astronomy professor Elisabeth Mills’ proposed space probe, PRIMA, has been chosen by NASA for funding and further investigation.

<!–

A space probe concept with a KU team member has moved on to the next stage of evaluation for a $1 billion mission set to launch into orbit in the 2030s.

The PRobe far-Infrared Mission for Astrophysics, or PRIMA, aims to detect far-infrared radiation, observable only from space. The last observatory to capture these wavelengths was the Herschel Space Observatory from 2009 to 2013. PRIMA is one of two probe concepts selected by NASA for further study, with KU’s Elisabeth Mills as a co-investigator on the team led by Jason Glenn at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

“This is one of the most uncharted regions of the electromagnetic spectrum,” Mills said in a news release from KU. “Lots of big questions in astronomy are just waiting for observations that can only be done at these wavelengths.”

This announcement followed after NASA announced the establishment of a new class of astrophysics observatories, known as probes, aimed at addressing significant astrophysical questions over the next decade. The agency intends to choose between a far-infrared or X-ray observatory to explore the formation of planets and the evolution of galaxies and black holes in the early universe.

Teams will receive funding from NASA over the next year to flesh out their plans and prototypes even further. Mills’ team will receive $5 million for Phase A, which takes place over the next year. NASA will then re-review the proposals and select one mission to move forward.

One of the significant questions that PRIMA aims to address is the origins of solar systems similar to our own. Researchers plan to analyze protoplanetary disks, which are the building blocks of planets, to determine the amount of water required for various types of planet formation. This investigation could shed light on the origins of Earth’s water, a mystery that remains unsolved.

“Far-infrared wavelengths are the key to measuring the total amount of water available to planets like Earth when they were young,” Mills said in the release. “No other wavelengths of light let us do this — to understand how early solar systems can assemble and deliver oceans’ worth of water to planets.”

Similar to the James Webb Space Telescope, PRIMA’s telescope will be cryogenically cooled to around 4.5 K, or -450° Fahrenheit, to enhance sensitivity by minimizing infrared background noise. Additionally, PRIMA will feature a wide-field camera, a high-resolution spectrograph for analyzing the chemical composition of cosmic objects, and cutting-edge kinetic inductance detectors developed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in partnership with Goddard to measure far-infrared radiation.

Glenn expressed excitement about the future developments for PRIMA, along with his colleagues.

“The PRIMA team is excited and grateful for this opportunity to develop a concept for the first NASA Astrophysics Probe Explorer,” Glenn said in the release. “Our extraordinary team of scientists and engineers is going to enable humankind to understand how black holes and galaxies evolved together and how planets got their atmospheres.”

Mills said that if PRIMA is ultimately chosen as the next probe mission, it would serve as a valuable resource for scientific discovery.

“PRIMA would provide a decade of access to wavelengths we haven’t been able to observe for years,” Mills said. “The technological leaps from its instruments would give us a whole new view of the sky, going deeper than ever to make stunning images that change the way we look at the universe around us.”