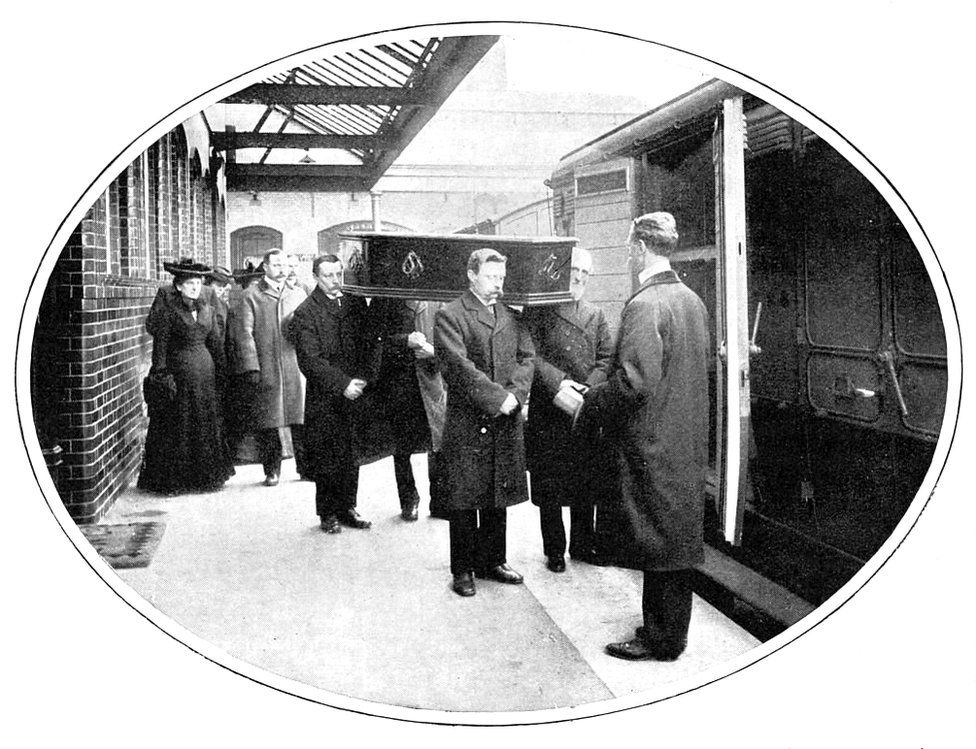

In November 1854, a train made its maiden journey from an annex of Waterloo railway station to the Surrey countryside. Rather than merry day-trippers looking forward to a bucolic break, it bore passengers dressed in mourning.

There were no cases and trunks. The freight consisted of coffins. Coffins containing corpses.

The train was destined for Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking.

The first burial at the site – twins, stillborn to a Mrs Hore from Ewer Street in Southwark – was in an unmarked grave, the standard for those whose loved ones could not afford anything more.

- The appeal of tombstone tourism

- The headstones with unusual stories to tell

- Play stations: Railway stops worth lingering at

The reason mourners faced a 46-mile (74km) round trip to bury their dead was because London’s rapid growth had pushed the population to 2.5 million. The capital, although home to hundreds of churchyards, was running out of room to house the dead.

The situation was described in an 1852 publication called What I Saw In London by David W Bartlett, an American author and academic.

He wrote: “Many times in our walks about London we have noticed the graveyards attached to the various churches, for in almost every case, they are elevated considerably above the level of the sidewalk, and in some instances, five or six feet above it.

“The reason was clear enough – it was an accumulation for years of human dust, and that too in the centre of the largest city in the world.”

The number of bodies far outweighed the capacity of the burial grounds. St Martin’s Church, measuring 295ft by 379ft (90m by 116m), received 14,000 bodies in 10 years.

A vault at a Methodist Church in New Kent Road was found to have 2,000 coffins piled one upon the other.

William Chamberlain, a grave-digger at St Clement’s, gave evidence to a House of Commons select committee in 1842.

He said the ground was so full of bodies that he could not make a new grave “without coming into other graves”. He and his colleagues were then instructed to chop up the coffins and bodies to make room for new ones.

“We have come to bodies quite perfect, and we have cut parts away with choppers and pickaxes,” he said.

“We have opened the lids of coffins, and the bodies have been so perfect that we could distinguish males from females and all those have been chopped and cut up.

“During the time I was at this work, the flesh has been cut up in pieces and thrown up behind the boards which are placed to keep the ground up where the mourners are standing – and when time mourners are gone this flesh has been thrown and jammed down, and the coffins taken away and burnt.”

Bartlett also cited an assistant gravedigger who recounted this gory tale: “One day I was trying the length of a grave to see if it was long and wide enough, and while I was there the ground gave way, and a body turned right over, and the two arms came and clasped me round the neck”.

It is obvious why a burial ground outside London was considered essential.

In 1851 parliament passed “An Act to Amend the Laws Concerning the Burial of the Dead in the Metropolis” – otherwise known as the Burials Act.

The following year, the London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company (the LNC) was formed with the ambition to create London’s one and only burial ground forever.

The company went to great efforts to make the new cemetery on the former Woking Common so attractive that Londoners would not even consider burying their loved ones elsewhere.

A prospectus advertising the new site declared it was so delightful that “solitude herself might here find retirement”.

The 23-mile (37km) distance between London and Brookwood meant that the traditional horse-drawn funeral cart (plodding at an appropriately funereal pace) could take up to 12 hours. Although Brookwood was the answer to the overcrowding, a better way to get there was also necessary.

Fortuitously, the newly established South Western Main Line ran alongside the border of the cemetery.

Notable graves

John Singer Sargent Painter. Plot 35

An American artist, who spent most of his life in London. He has been described as the most fashionable portrait artist since Sir Thomas Lawrence.

Horatia Nelson Johnson Nelson’s granddaughter. Plot 24

Horatia was the seventh of nine children born to the daughter of Lord Nelson and Emma Hamilton.

Sarah Eleanor Smith Widow of Captain Edward J Smith, Captain of the Titanic. Plot 25

Mrs Smith was gravely injured when she was knocked down by a taxi in London and died in April 1931.

Dame Rebecca West Author, reporter, literary critic. Plot 81

Her book ‘Henry James’ (published 1916) established her literary reputation. She was a supporter of the suffragettes. And she found herself on Hitler’s blacklist.

Thomas Humphrey Cricketer known as the Pocket Hercules. Plot 82

Mr Humphrey earned his nickname because he was short and could hit powerfully. During his career he scored 6,687 runs in 381 innings, being not out 18 times.

The Necropolis route passed Richmond Park and Hampton Court on its way out of the capital, scenery described by one of the railway’s founders as “comforting” and once again appealing to the moneyed classes.

Not everybody was convinced. The London and South Western Railway, operating out of Waterloo Bridge station, was particularly squeamish about the idea of their own passengers using carriages that had earlier been used to carry coffins and funeral parties.

The Bishop of London, Charles Blomfield, was also horrified at combining the railway and burial services. He addressed a House of Commons Select Committee, stating the “hurry and bustle” connected with rail travel rendered it “inconsistent with the solemnity of a Christian funeral”.

The bishop was also concerned about the remains of those who had led “decent and wholesome lives travelling alongside those whose lifestyles had been morally lax”.

Societal objections included discomfort at the idea of mixing social classes and the mixture of different denominations, or even completely different religions.

The solution was to make the Necropolis train an entirely separate service, with their own carriages and timetable, and six separate categories of ticket for the living and the dead.

The coffins were segregated so that the bodies of Anglican worshippers travelled behind the carriages for Anglican mourners, and the same for those of all other (or no) religions.

First, second and third class travel was provided for conformists, and another section with the same classes for non-conformists.

First class allowed families to select a site anywhere in the cemetery and, for an additional cost, the erection of a permanent memorial. It cost about £3, today’s equivalent of about £270.

Second-class funerals limited the choice of location, but cost just £1 (about £90 today). Third class was reserved for pauper’s funerals and those buried at a parish’s expense.

The offices, morgue and chapels of the London Necropolis Railway were based underneath the arches on Westminster Bridge Road.

Trains ran every day and would be met at Brookwood by a team of black horses to haul the carriages down the slope into the cemetery.

Fares were limited by the act of parliament establishing the LNC, and they remained unchanged for the first 85 years of its 87-year operation.

Anecdotally, unscrupulous travellers wanting to go to the Woking area, including many golfers, would disguise themselves as mourners to take advantage of the bargain rates.

The LNR continued until World War Two when, during the night of 16 April 1941, in one of the last major air raids on London, the station was hit by high explosive and incendiary bombs.

The track and buildings were demolished.

Post-war, funeral train services did not restart. Motor cars and hearses were becoming more popular and were more convenient.

The London Necropolis Railway had come to the end of the line.

Today, the Westminster Bridge Road terminus building still stands as Westminster Bridge House and the track bed and platforms still exist at Brookwood.

National Rail also installed a section of track at the Brookwood site to commemorate the venture.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]

Around the BBC

-

Necropolis – London’s railway for the dead