Angeline Boulley, Cynthia Leitich Smith, and Debbie Reese discussed Native work for young readers—and Boulley made a big announcement.

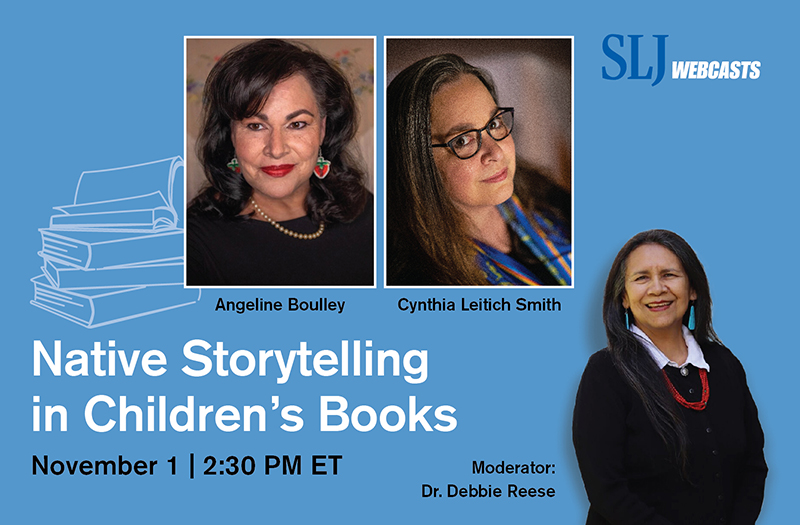

Best-selling authors Angeline Boulley and Cynthia Leitich Smith discussed the responsibility of writing Indigenous characters and storylines in children’s and YA books and literary devices used by Native authors in SLJ ’s “Native Storytelling in Children’s Books” webcast on Wednesday, November 1.

Boulley, an enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Trip of Chippewa Indians, also broke a little publishing news. During the webcast, Boulley shared that she has a deal with MacMillan for a third and fourth book in the “’Firekeeper’ chronicles,” as she called them.

“It has not been publicly announced yet, but it will be shortly,” she said of the new books that will connect to 2022 Printz Award-winning Firekeeper’s Daughter.

With that, she previewed a bit of what readers can expect from the forthcoming novels.

“Firekeeper’s Daughter obviously involved the element of fire,” Boulley said. “My second book, Warrior Girl Unearthed, involved the element of earth. So we still have air and water.

“I’m just so fortunate to be with MacMillan, and that they share my vision in what I’m trying to do in telling stories that are interconnected, but don’t look like the sequels maybe they’re used to.”

In Firekeeper’s Daughter, readers met Perry as a six-year-old. The character becomes the teenage narrator in Warrior Girl Unearthed. Readers can expect to see characters from the first two books in future novels, even if—as Boulley notes—it’s not in the way they find them in a typical sequel or traditional series.

This idea of interconnected stories was one theme Boulley and Smith discussed during the hour-long conversation, moderated by Native scholar Debbie Reese, Tribally enrolled at Nambé Owingeh.

“All of my Indigenous books are somehow interconnected,” said Smith (Mucogee citizen). “When we return to communities in our books, it’s not a marketing approach; it’s not a shortcut of any kind. This is a literary device we’re using to show intergenerational extended family and community ties by conveying it through several books over time and, in my case, across formats, genres, and age markets.”

Boulley agreed and said it is a device not fully understood outside of the community.

“This is a storytelling technique that so many Native authors do, and I don’t think it gets properly recognized,” she said. “Louise Erdrich—you might meet some character three books back that is the main character in a story Louise writes decades later. [It’s] the same thing Cynthia did with Hughie and that I did with Perry.…That’s such a community and extended family worldview that just is natural to Indigenous authors that seems like a very specific technique to people who are not Native. This is how we tell stories. The connections are so interwoven. That’s a part of identity and a part of finding community … this rich layered nuanced thread of community that comes through.”

Smith elaborated.

“When you look at my body of literature, Angeline’s body of literature, these books are going to seem to echo in certain ways,” she said. “But that echo isn’t a mindless or lazy repetition. That echo is intentional, and it is to bring more resonance to the conversation. It is to communicate something that’s vital and necessary.”

As they write these stories, Boulley and Smith are very cognizant of the age of their readers, their life experiences, and the difficulty of some subject matter.

“[Harvest House] does touch on some trauma that is real that is happening in Indigenous country,” Smith said, discussing her 2023 YA title. “I’m very aware of the need to be sensitive to our kids who are facing this in real life, especially for slightly younger teens. Giving them the slant of a ghost gives them a little bit of protective distance. It gives them a little distance with the fact that what happened, happened over some time [ago].”

The book also offers “heroes they can vicariously root for and facilitate change,” said Smith.

Boulley always considers the youngest readers she might have, even for a book that is designated for readers 14 and older. She makes a point to be “mindful not to trauma dump,” especially for the young Native readers, allowing them “breathing room,” as well as offering resources.

“I feel like writing for children and teens, the authors have this unspoken agreement to first do no harm,” she said. “I’m very honored, and I consider it an important responsibility to make sure I’m not sugarcoating the issues that young people in my Tribal community and many others face, but I am approaching it with very careful consideration and inclusion of resources and not leaving that youngest reader—who may have experienced these issues or a loved one member may have experienced—I’m not leaving them hanging. I’m providing support, providing resources, and taking into account where I place those incidents in the story in terms of pacing.”

Hear more from Reese, Boulley, and Smith by registering for the webcast and watching the full conversation on-demand.