More than 20 mysterious signals have been detected in space after a team of Australian researchers began sifting through intergalactic signals.

Their success has been likened to sorting through grains of sand at the beach.

It was the first trial of new technology developed in Australia by astronomers and engineers at Australia’s national science agency CSIRO.

The results of the study have been published in the Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia.

International Centre for Radio Astronomy’s Andy Wang, who led the research, said his team found more astronomical objects than they had expected.

“We were focused on finding fast radio bursts, a mysterious phenomenon that has opened up a new field of research in astronomy,” Dr Wang said.

The specialised system used in the research was called CRACO.

It was created for CSRIO’s ASKAP radio telescope to detect mysterious fast radio bursts.

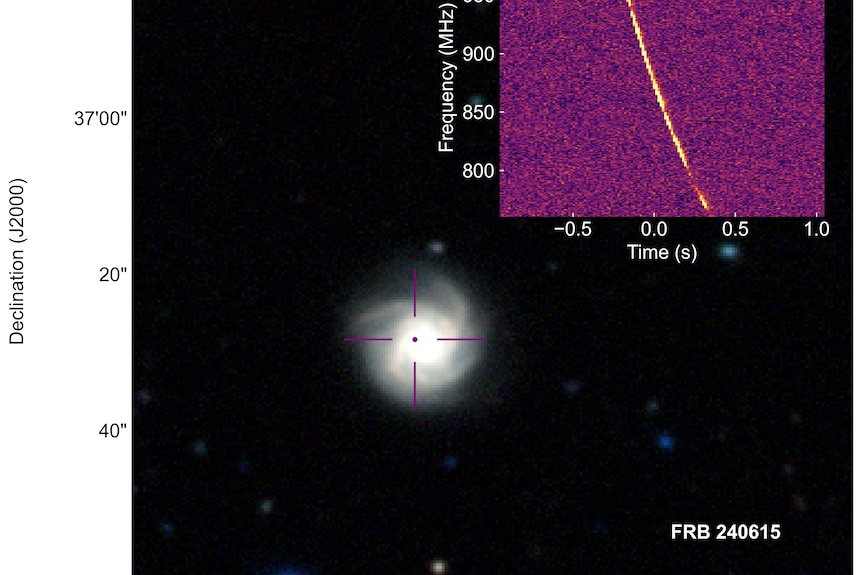

An example of a galaxy hosting a fast radio burst identified by the CRACO system. (Supplied: Yuanming Wang, the CRAFT Collaboration)

By using the new technology, researchers initially found two fast radio bursts and two sporadically emitting neutron stars and improved the location data of four pulsars.

But they have now located more than 20 fast radio bursts.

“CRACO is enabling us to find these bursts better than ever before. We have been searching for bursts 100 times per second and in the future we expect this will increase to 1,000 times per second,” Dr Wang said.

Radio astronomer Laura Driessen from the University of Sydney said a fast radio burst was a flash of light that in most cases was far outside of our galaxy, and technology such as CRACO was used to probe its origins.

But at present, it is unknown how fast radio bursts occur.

“We’ll be able to use them sort of as tools to probe the universe, but we also want to find out what’s going on with them in the first place,” Dr Driessen said.

“What’s making these really bright, really short flashes of radio light from all over the universe, all distances, all directions, just kind of everywhere.”

So what is CRACO?

Researchers said CRACO was a collection of computers and accelerators that are connected to the ASKAP radio telescope.

Prior to its adoption, the ASKAP radio telescope had been using CRAFT to identify fast radio bursts.

CSIRO astronomer and engineer Keith Bannister, who developed CRACO, said the new technology tapped into the ASKAP radio telescope’s live view of the sky to find fast radio bursts.

“To do this, it scans through huge volumes of data — processing 100 billion pixels per second — to detect and identify the location of bursts,” Dr Bannister said.

“That’s the equivalent of sifting through a whole beach of sand to look for a single five-cent coin every minute.”

CSIRO’s Keith Bannister led the engineering team for the CRACO instrument. (Supplied: CSIRO)

Dr Driessen said fast radio bursts were detected by looking at its time and frequency.

“So we’re just sort of treating the sky as all one big pixel and working out if anything inside there changes in brightness over time,” she said.

“So we’re looking for sort of flashes in space, but in just one giant pixel. And if you imagine your phone as one pixel, you wouldn’t be taking particularly good photos.”

Laura Driessen says the use of CRACO will increase the number of fast radio bursts that are localised. (Supplied: University of Sydney)

Dr Driessen explained the previous method required extra steps to locate fast radio bursts, which the CRACO does not need.

So instead of searching for one pixel, she said CRACO was akin to searching in the whole picture

“Rather than searching just the brightness in the sky in a general patch, they’re looking at an image and seeing exactly where these flashes are coming from,” she said.

What does this mean?

According to Dr Drissen, the use of CRACO will increase the number of fast radio bursts that are localised, meaning their position in the universe will be known.

“This is important because if we only sort of know their general direction, we can’t say which galaxy the fast radio burst came from,” Dr Drissen said.

“This is important because the galaxy it came from gives us a lot of information about what could have made it.”

Dr Drissen said there was information about a handful of fast radio bursts.

“If we can link each fast radio burst up to the galaxy that it’s coming from, we can measure using other techniques at other frequencies,” she said.

“So optical in particular, we can measure the distance to that galaxy, and that’s really where those fast radio bursts are going to provide that key probe of the universe.”

The CRACO system was developed after a collaboration between the CSIRO and Australian and international researchers.

It was partially funded through an Australian Research Council grant.