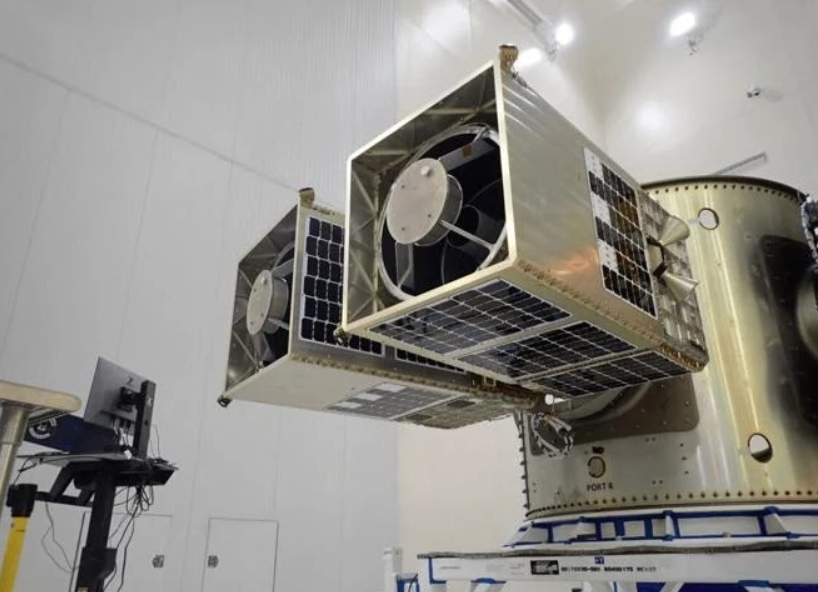

Two satellites are seen at the Corning Advanced Optics facility in Keene, equipped with hyperspectral imaging sensors the plant engineered and manufactured. The satellites seek out light waves created by oil and natural gas pipeline leaks, then generate signatures by reflecting the waves back from space. (Courtesy of Corning Inc.)

New imaging technology from the Keene division of a worldwide glass, ceramics and optics company is helping cut down the time and resources needed to identify environmental concerns like leaking oil pipelines.

Employees of the Corning Advanced Optics plant on Island Street in Keene, have worked with San Francisco-based Orbital Sidekick (OSK) to develop sensors used on three low-earth orbiting satellites OSK launched this year that use hyperspectral imaging to find oil and natural gas leaks.

Hyperspectral imaging is a form of sensing technology that analyzes light striking the sensors on the satellites to find substances, according to Leon Desmarais, Corning’s product line leader who’s based in Keene and heads the business end of the company’s OSK partnership.

OSK is primarily working with investors in the oil and gas industry across all its projects, Desmarais said, so from its perspective, substances its satellites work to detect include liquid hydrocarbon and methane leaks.

The three satellites currently orbiting the planet with Corning’s sensors make up what OSK calls the GHOSt constellation, an acronym for Global Hyperspectral Observation Satellite, according to industry news outlet Via Satellite. The satellites, which are about the size of an average dishwasher, send back imagery from the ionosphere, about 310 miles above the Earth’s surface.

“Hyperspectral imaging can be used from a microscope all the way up to space, so it’s very diverse,” said Desmarais, who lives in Antrim. “… Every substance on Earth has a unique spectral signature, as long as you have enough resolution to be able to see it. That’s what our technology does is enable that resolution to see it.”

Typically, analysts look for pipeline leaks through methods within the atmosphere like airplane flyovers and on-the-ground analysis. But through those approaches, “it takes a lot longer to get that data back,” Desmarais said.

“With enough satellites up there, [analysts] can revisit the same sites more often, see changes over time, see where there may be a leak and get it fixed faster,” he said.

The satellites were launched on April 15 and June 12 and with dozens of other spacecraft on SpaceX’s Transporter 7 and Transporter 8 rocket missions, according to the European Space Agency, and OSK released its first imagery from the constellation on Aug. 23. Corning started working with OSK in 2019, and began developing its portion of the GHOSt project about two and a half years ago, Desmarais said.

The Keene-made sensors distinguish the color bands of the electromagnetic waves, or light waves, and uses the color data to identify objects or substances on land from outer space, Desmarais said. In a Corning news release, the company stated that spectral signatures are generated based on how a material reflects or emits the light waves.

Corning states its sensors can cover a light wave range of 400-2,500 nanometers, including infrared and ultraviolet light. For reference, the human eye can only see light waves from 380-700 nanometers, according to NASA.

In the Corning news release, OSK CEO Dan Katz said the GHOSt sensors can capture 100 times more information than other satellites.

“We can now survey an entire transcontinental pipeline in hours rather than weeks,” Katz said. “This year alone, we’ll monitor 124,000 miles of pipeline.”

Ryan Barlow, background, Eric Bower, left, and Jesse Brown, right, who are Corning employees at the company’s Keene plant, pose for a photo with a hyperspectral imaging sensor they helped develop for satellites launched by San Francisco-based Orbital Sidekick. About 200 people have worked on the hyperspectral project in Keene. (Courtesy Corning Inc.)

About 200 people are involved in manufacturing the sensors at Keene’s Corning facility. Just 15 of them are the engineers behind the sensor technology, Desmarais said. While there is support from the company’s main Sullivan Park campus just outside the namesake Corning, N.Y., he called it “primarily a Keene project.”

Jesse Brown, a hyperspectral system integration engineer based in Keene, said in the company news release that the facility’s staff were proud to see their work take flight.

“At 3 a.m. on launch day, we were on the ground cheering,” Brown said in the release.

Imagery produced by the satellite sensors developed locally will have a global impact on environmental research and climate change mitigation, Desmarais said. The Keene plant’s outer space work builds upon earlier terrestrial system projects involving drones and airplanes, he noted.

“In New York, the [State University of New York] system has been using [terrestrial systems] to find algal blooms, so we’re looking for harmful algae on lakes,” Desmarais said.

Previous equipment the company has produced in Keene includes sensors for three telescopes with mirrors used on NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, which the plant worked on from 2004-2010 with a team of 75-100 employees.

In the time since, Corning’s Keene plant has turned to develop products with more commercial applications, like the OSK hyperspectral sensors, according to Desmarais.

“In the last eight to 10 years, we’ve been doing a lot more on the commercial imaging side, making some off-the-shelf products that we can market to anybody who wants to buy them and attending different trade shows that are more focused on this commercial market,” he said.

OSK plans to end the GHOSt satellite mission on April 15, 2027, according to the European Space Agency. Meanwhile, Desmarais said Corning’s Keene employees are developing even more space-related projects, though those aren’t quite ready for launch.

This article is being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information, visit collaborativenh.org.