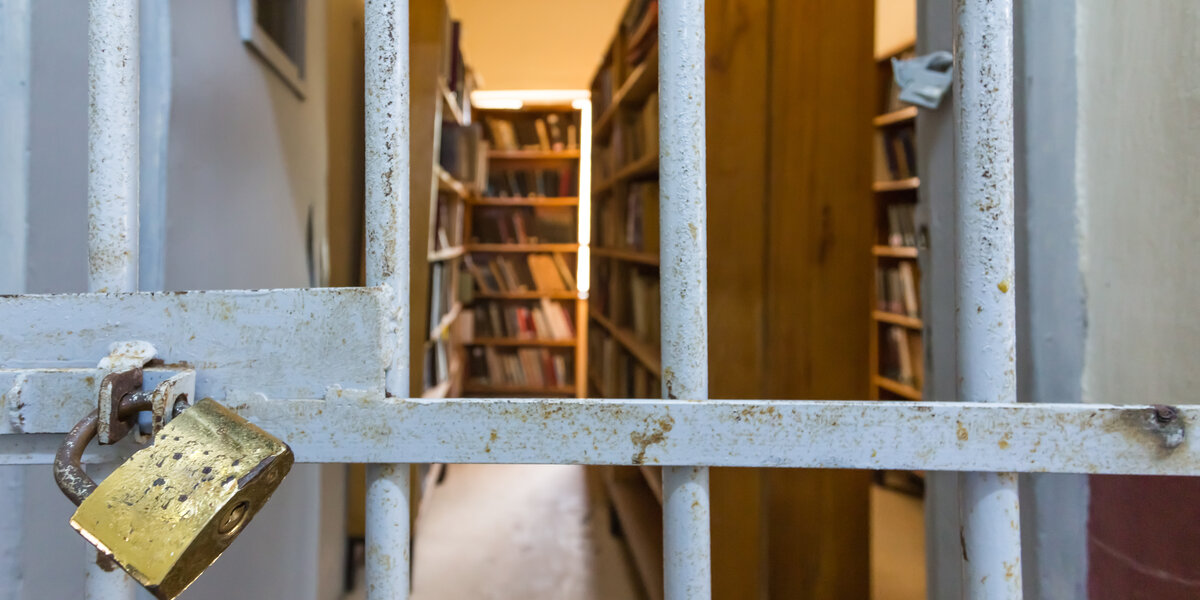

Book bans aren’t just on the rise in schools and public libraries. They’re happening in prisons, too.

A new report by PEN American found that prisons “are the largest censors in the United States” and that single state prison systems “censor more books than all schools and libraries combined.”

The report said that carceral censorship is ubiquitous in the U.S. All 50 states and Washington, D.C, have engaged in some type of ban.

Some of that censorship is seen in public school and library book bans we’re used to hearing about. But prisons believe that the content of the book itself can be a threat, because it could give a prisoner “ideas.”

This kind of censorship is justified by security. For example, Michigan listed a Spanish-learning book as a “threat to the good order” of the prison, because incarcerated people could learn a language that staff might not understand.

In the “security” category are many books pertaining to or referring to magic, like the “Fantasy Artist’s Pocket Reference,” “Dungeons & Dragons” manuals, and mind-reading manuals.

The most common reason for bans is “sexual content,“ which can include art, scientific texts on gynecology, magazines that offer “sex tips,” and literature about trans people.

Books categorized as “racially inflammatory” are often censored. In Louisiana, at least 144 of these books are banned, but only 4 of those are white supremacist texts. So the literature that’s getting banned is by and large written by Black and brown authors.

But content-neutral bans are far more popular. Books can be banned because prisoners received too many titles that month, or because they received free or used books. Titles can be returned to sender if they’re not mailed according to specific requirements, like whether they’re mailed on white paper or have a hard cover.

Idaho blocked more than 2,000 publications in one year through an “approved vendor“ rule.

“Prison censorship is distinguished not just by its targeting of specific titles or topics,” the report said. “But by the sheer number of tools in the censors’ toolbox.”

PEN America said that banning books can lead to the widespread suppression of “learning and information” itself.

Steve Wilson, an incarcerated man, wrote that prisons “just don’t want incarcerated folx to have books. [We] have video games, movies, tv, but no books. [They] just don’t want people to be thinking critically.“

Incarcerated people deserve to explore ideas, and they deserve to express themselves, to engage with mainstream culture, and to simply relax with a good book.

“Books have become like an extra apple or orange here—not something to be savored or saved until I hunger for it but rather something I must consume rapidly, guardedly, before it can be taken and thrown in the trash,” wrote Ken Meyers, incarcerated in Pennsylvania.

While many prisons systems say they have an appeal process for censorship, accounts from incarcerated people challenge that narrative. Four out of seven Texas respondents told PEN American that there was no appeals process, despite what the system said. 25% of all respondents said that filing an appeal was fruitless. The muddy, confused procedures keep many incarcerated people from even attempting to challenge these policies in the first place.