Since the holiday season triggers trips to New York City, here are write-ups of six art exhibitions now at Manhattan museums — in north-to-south order — for your short list.

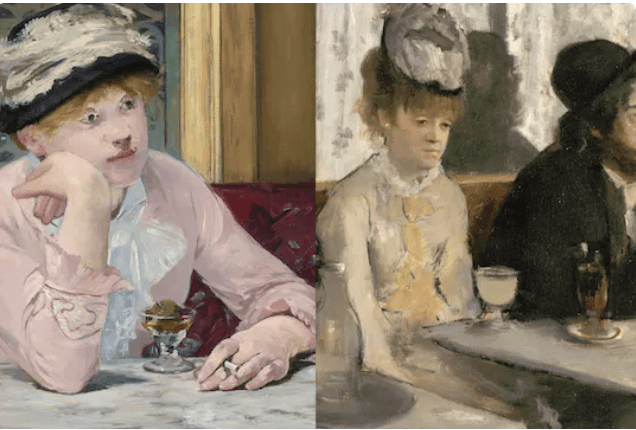

The big show is “Manet/Degas,” on view through Jan. 7 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Ave. at 82nd St.). The crowded, maze-like galleries, with white text on lavender walls, offer a narrative about these dissimilar French geniuses, who pioneered the painting of modern life. Above all, the exhibition brings together well over 100 terrific paintings, most thrillingly “Olympia,” Edouard Manet’s naked, blasé can-can dancer, making her maiden U.S. appearance. Manet, some of whose works — including the partially reassembled “Execution of Maximilian” — were acquired by Edgar Degas after his death, looms larger in this pairing. Much is made of the artists’ social overlapping; a gallery titled The Morisot Circle — painter Berthe Morisot posed for Manet, married his brother and exhibited with the Impressionists, of which Degas (but not Manet) was one — is a bullseye.

From “Manet/Degas” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

To gain entrance to “Manet/Degas,” one joins a “virtual exhibition queue” by scanning a QR code and awaiting a text message. While waiting, head for the Robert Lehman pavilion, where “Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism,” on view through Jan. 21, is a rewarding octagonal experience. French for wild beasts, “fauves” was a critic’s put-down of the artists whose loosely painted works in seemingly unnatural colors were shown at the 1905 Salon d’Automne. Two well-known paintings by Henri Matisse — “Young Sailor II” of 1906 and the following summer’s “View of Collioure,” the Catalan village where the Fauves interbred, so to speak — are here, but the chance to see work by the group’s other leader, André Derain, in dialogue with that of Matisse, is especially welcome.

From the exhibit “Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism.” Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Frick Collection has been camping out at the Frick Madison (945 Madison Ave. at 75th St.), the former Whitney Museum and Met Breuer. On view through Jan. 7 is the first Frick exhibition devoted to a Black artist: “Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick.” A Philadelphian, Hendricks was solidly trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, which funded his European travel in the late 1960s. Overseas, as well as in American museums such as the Frick, said to be his favorite, he admired “grand manner” portraiture while noting the absence of non-elite subjects, particularly persons of color. This he began to correct, painting full-length portraits of ordinary, yet fashionable, folks. Opening with “Lawdy Mama,” a portrait from the hips up of a woman, glowingly surrounded by gold leaf, whose Afro follows the curve of the arched canvas, the show includes 13 other top works. One of the best, in a gallery of white-dressed subjects: “Lagos Ladies (Gbemi, Bisi, Niki, Christy),” showing hotel cooks who captured Hendricks’s fancy at a Black culture festival in Nigeria.

“Lawdy Mama,” 1969. Barkley L. Hendricks. Left and right: busts by Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828). Photo by Richard Selden.

Can you say Ruscha? It’s pronounced “roo-shay” by the 85-year-old artist (he turns 86 on Dec. 16) whose work is spaciously displayed in “Ed Ruscha / Now Then,” on view through Jan. 13 at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd St.). In 1956, Ruscha moved to Los Angeles from Oklahoma City for art school, latching onto midcentury vernacular culture. He is known for obsessive, deadpan artist’s books, the first of which was “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” (a copy hangs from a wire). At the retrospective’s midpoint, one passes through a recreation of his “Chocolate Room” from the 1970 Venice Biennale, shingled in sheets of paper screen-printed with chocolate paste. Ruscha is one of the chief practitioners of word or text art, examples of which line the walls. There are also large gas station paintings; the literally fantastic “Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire”; and several intriguing detours.

Foreground: “Every Building on the Sunset Strip,” 1966 (detail). Background: “Hurting the Word Radio #1,” 1964, and “Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas,” 1963. Ed Ruscha. Photo by Richard Selden.

Most Black portraitists since the 1970s have drawn inspiration from Barkley L. Hendricks (see above), but the artist of “Henry Taylor: B Side,” on view through Jan. 28 at the Whitney Museum of American Art (99 Gansevoort St.), in choosing a “naïve” style, seems to be following in Alice Neel’s footsteps. Born in Ventura, California, in 1958, Taylor drew patients at his workplace, Camarillo State Mental Hospital, while gradually completing a BFA in his late 30s. Of the exhibitions described here, none has more visual appeal. Taylor’s portraits — of friends, strangers and celebrities, some deceased victims of police violence— are big, grabbing you from across the high-ceilinged galleries. There are also cases with painted and collaged cereal boxes and cigarette cartons, a roomful of mannequins in Black Panther jackets and, opposite the museum’s Hudson River-facing picture window, a charcoal-and-mixed-media mural on four walls, the long sections titled “Timbuktu” and “Mississippi.”

“Elan Supreme,” 2016. Henry Taylor. Photo by Riichard Selden.

In its new Lower East Side location, the International Center of Photography (79 Essex St.) is showing work by a contemporary photographer based in Washington, D.C. “Muriel Hasbun: Tracing Terruño,” on view through Jan. 8, surveys the career of a Georgetown University and George Washington University alumna who taught at the Corcoran for two decades. The key to Hasbun’s multilayered, mostly black-and-white images is her ancestry: she grew up in El Salvador, the granddaughter of Salvadoran and Palestinian Christians on her father’s side and Polish and French Jews on her mother’s. Comparable to the French word “terroir,” for Hasbun “terruño” expresses the concept of home. The exhibition features her series “Santos y sombras / Saints and Shadows” of the 1990s; “X post facto (équis anónimo)” of 2009-13, based on x-rays from her father’s dental practice; and the current “Pulse: New Cultural Registers / Pulso: Nuevos registros culturales,” which melds, on anodized aluminum plates, images from her mother’s San Salvador art gallery and seismograms from El Salvador’s civil war years.

Image by Muriel Hasbun in the show “Tracing Terruño.” Courtesy ICP.