A couple months ago I found myself alone in a Northern California beach town, walking the hills and talking into a recording app on my phone. None of my usual ways of writing were working anymore. Not the laptop or the overpriced word processor with no distractions and an e-ink screen. Pen and paper— my method of choice up until a few days before—didn’t feel free and easy like it once had. At night, when I played the dictations back in order to transcribe them, I heard mostly half-formed thoughts; fragments of dialogue; a word to slip in somewhere for mood; long, deep sighs; the crunch of my footsteps on gravel.

A dozen books into my career, I’m still figuring out how I work and what I need. For years I’ve been drawn to other writers’ routines and processes, scouring interviews for rituals, raising my hand at readings to ask writers how they do it. At my own readings, when asked, I give honest answers: A song playing on repeat. A candle. A quick walk when I’m stuck. Keeping books I love within reach, turning to a random page for inspiration. All of these things have worked for me at one time or another, still do work for me a lot of the time. When they don’t, I tell myself I need a day of writing in bed, or a clear desk, or a dedicated room in my apartment, or an office outside of my home. I’ve tried all of these. They’ve all been right; they’ve all failed me. It depends on the day.

And then, sometimes, when I least expect it, there are the rare, exquisite, ecstatic experiences of writing, when the story bursts out, and I struggle to type as fast as I need to, afraid the sentences are going to fly out of my grasp.

A dozen books into my career, I’m still figuring out how I work and what I need.

Here’s the story of one of those times:

It was 2020, the era of staying home, and after many years of publishing young adult novels, I had just finished writing my first novel for adults. For months, all time not spent with my wife and daughter was time spent writing. My clear desk and my songs on repeat and my candles and my tea and my slippers and my closed door kept me afloat. And my characters did, too—the restaurants they went to, the people they fell in love with, their moments of growth and stagnation, their small wounds and pleasures. And then I was finished with them, for a time, and I turned my focus to long walks with my daughter.

We had only just moved to our duplex in San Francisco three days before the shelter in place orders. We barely knew our new neighborhood yet; these walks were our introduction. I emerged after months spent in a room to secret staircases cut into hillsides; views of the downtown skyline surprising us around a corner; a chicken named Lady Gaga who lived at the edge of a front yard a couple blocks away. My daughter and I walked and walked and, together, we fell in love with the place we lived now. Each colorful Victorian. Each empty park and playground. Each person we passed, waving from a safe distance.

It was strange, wandering our neighborhood’s streets and finding them so quiet and empty. We felt the absence of people and noise and life. All the shops had “closed” signs in their windows. At the little park with cherry trees and a stone bench overlooking Twin Peaks and the downtown skyline and the very top of the Golden Gate Bridge, we imagined a pair of dogs playing. One was a little white fluffball, the other a golden retriever. We ran through dozens of names for our imaginary dog friends, settled on Daisy and Danny. And who were their owners? We picked names for them, too. The thimble-sized pink house around the corner belonged to one of the men, and the other man lived up the street in the blue apartment building with the palm tree, and as the months went on and our stories grew, the men we made up fell in love and got married. We lay on the grass and imagined the wedding (a fiasco, I’m afraid) and then I sat up.

“This should be a book,” I said.

My daughter agreed.

We rushed home and I grabbed the laptop, perched at the edge of the bed, and began. It was effortless, joyful. Time became a blur. It didn’t matter where I was. Music could be playing or not playing. I didn’t need any of it. I didn’t know what I was writing. Was is it a short story or was it a novel? A single book or a series? It didn’t matter.

I wrote with the feeling of my daughter’s hand in mine as we explored our neighborhood streets. With the expansiveness of time on days when nothing was expected of us. Maybe most of all, I wrote from a place of wanting. Here we’d been, living downstairs from our dear friend who we couldn’t be with, new neighbors all around us who we hadn’t yet met. I wrote remembering all the apartments I’d lived in throughout my life. The teenager who babysat me by our shared pool when I was a little kid. The old woman with the tremor, holding her hands out for a plate of my mother’s scones. When I was in grad school, my wife and I lived across from a man who’d knock on our back door with bowls of matzo ball soup and under an opera singer who’d practice late at night, piano keys plinking, a high soprano. Downstairs to the left were a poet and attorney who kept their bed in the living room so the office could have a door. To the right was a traveling coffee saleswoman whose tabby cat we looked after whenever she was on the road.

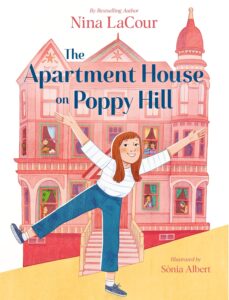

I wanted that kind of life back, breathing the same air as the neighbors, moving casually from one apartment to another, footsteps always above or below or right past the door on the landing. I wanted my daughter to have that kind of life—who knew if or when we’d have it again?—and so I put a girl like her into the book, gave the girl a set of keys, established that she’d lived in the big, pink, Victorian apartment building for her entire life—nine whole years—and knew its inner workings, its residents, its quirks, its sounds.

I finished the book, named it The Apartment House on Poppy Hill, decided it was, in fact, the first in a series. Who could have imagined? An entire book, written in just a few electric days. A gift, to work that way.

And yet—here’s this other novel I’ve been working on, the one I sighed over in my voice memos and couldn’t get down. After a stretch of floundering months something broke open and now I know what I’m doing. Hard-won clarity is a gift, too. Because I’ve spent years immersed in this book I’m writing now, it’s real to me in a new and distinct way, as though its characters are sitting on my living room sofa as I write this, drinking whiskey and listening to records and shaking their heads and laughing. Timing in publishing is forever dissonant. You work on a book and then you wait, sometimes for a very long time, and it comes out when you’re deep in another project, and you’re reminded of how strange and wonderful a thing it is to write a book, how unfamiliar each time. Right now, for me, it’s pen and paper, coffee, and a song.

__________________________________

The Apartment House on Poppy Hill by Nina LaCour, illustrated by Sònia Albert, is available from Chronicle Books.