Throughout the second half of the 20th Century, the weekly trip to a local newsagent to pick up your favourite music magazine was a rite of passage for millions of British teenagers.

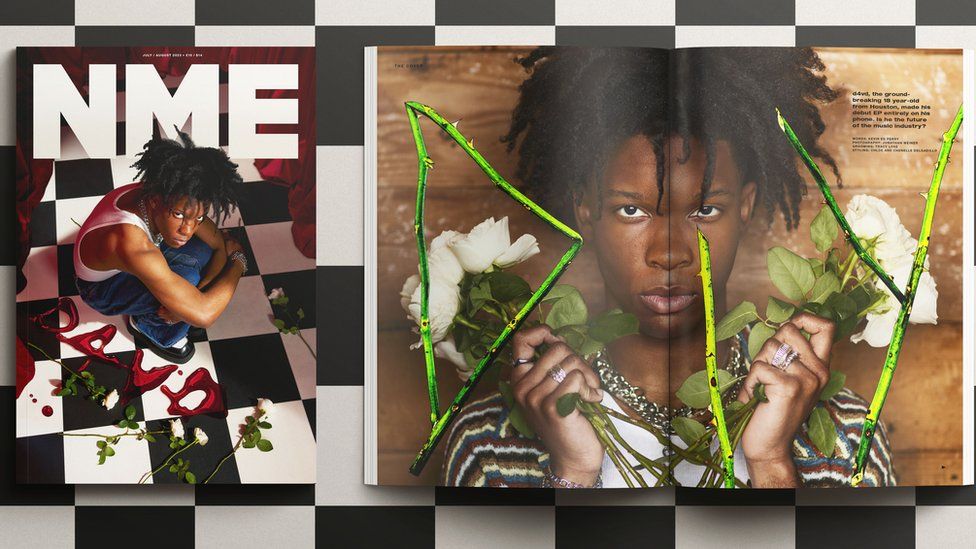

The iconic covers of titles like NME, Melody Maker and Sounds were graced by everyone from the The Beatles to The Clash, Nirvana and Oasis.

Then came the internet and, like the music industry, the magazine business would never be the same again.

But fast forward to this century and vinyl has done something that very few expected – like an ageing, once-huge rock star it made a comeback.

As records have returned, albeit in a different form, now British music bible NME is back with a similar twist.

The new NME magazine has a £10 cover price, will be published every two months, with a small print-run – in the hundreds rather than the hundreds of thousands.

Its owner – Singapore-based Caldecott Music Group – says the new print version is aimed at “super-serving our super fans”.

“The NME as a whole is something where we believe it is much more than just a product, it’s more than a service, it’s more than the audience,” Caldecott’s chief executive and founder Meng Ru Kuok told the BBC.

“In fact, it’s the eternal teenager, that should always be young.”

All the Young Dudes

NME has documented everything from Elvis to EDM in the 71 years since it was established as a weekly newspaper.

Just over a decade after its launch, circulation had hit more than 300,000 as Beatlemania swept the world. Young music fans would pore over every page, crammed with the latest music news, interviews with the world’s top bands and introductions to artists that may just be the next big thing.

There were record reviews, gig listings and classified adverts enticing readers to buy that elusive piece of must-have clothing or even form a band of your own.

Magazines like NME were not just ink-covered pieces of paper, they were magical windows to a world of untold glamour and sleaze. Most importantly they were cool. Very cool.

But cool was not enough to survive the internet’s onslaught. When NME’s sales, like most of the print media, plummeted – in 2014, down by around 95% from its peak – its then-publisher, Time Inc UK, took the decision to make it free.

- How print is surviving the digital age

While that brought its circulation back to those mid-1960s levels, the approach proved unsustainable and for the NME the printing presses ground to a halt in 2018.

NME would be “focusing investment on further expanding [its] digital audience,” its owner said.

That did not stop the hashtag “RIP NME” trending on social media as musicians shared images of when they were on the front cover.

As the magazine returns to its print origins the strategy is not about producing hundreds of thousands of copies that will be available in every newsagent in the UK.

Rather, the challenge faced by the new print version of NME is harnessing that cool energy that had built over the decades.

Key to this may well be a more recent phenomenon, FOMO, or fear of missing out.

“The more rare a physical thing is the more value it has, that’s never more true than now,” said Conor McNicholas, who edited NME between 2002 and 2009.

“Digital work disappears like sand through your fingers. Physical items like a limited sneaker drop or a vinyl album release feel special, something for the true fans,” he added.

- NME: End of an era of excess, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll

- What Asian fans did for Taylor Swift concert tickets

And that is why the records sold in the 21st Century are high-end collectibles, rather than the mass market products of previous decades.

Albums now often come with any number of special features – limited edition, boxsets, remastered, on heavyweight, coloured vinyl, packaged in gatefold sleeves, with exclusive, never-seen before art prints etc. And all of this is likely to come with a hefty price tag.

Back For Good

Now NME too is aiming to replicate vinyl’s reinvention as a fancier, rarer, pricier product than its mass-market predecessor.

“We believe that that scarcity also brings more attention to the artists on the cover, we believe it brings more attention to the content in the product itself. And that scarcity is only a good thing for helping to, again, achieve the goal,” Mr Kuok said.

NME is not alone in its approach to magazine publishing.

According to media research firm Enders Analysis, there were 330 magazine launches last year, with many of them being niche publications.

Magazines like this are often published just a handful of times a year and have relatively high cover prices.

“For the most part, print editions are like vinyl records: offline and high quality but commercially a very small part of the overall media landscape,” Abi Watson, media analyst at Enders Analysis, said.

One example of this kind of magazine is We Are Makers, a quarterly publication aimed at artisan craftspeople. It has no adverts and a cover price of £18.

“In today’s digital age, everyone’s attention is scattered online, making it harder for creators to be noticed,” Kate and Jack Lennie, who run the magazine, said.

“We wanted to bring back a more meaningful experience through print, where you can fully appreciate the content without constant online distractions,” they added.

Mr Kuok also highlighted that his decision to bring back NME as a high-end, low volume magazine was not aimed at making huge amounts of money.

It is not “a billion dollar revenue line,” he said. “Thinking that in 2023 would be foolish, right?”