Abstract

This study identifies the association between heated tobacco product (HTP) use and occupational falls, considering lifestyle variables. A nationwide web-based cross-sectional study between September and November 2023 analyzed data from 18,440 workers in Japan (mean age: 43 years; women: 43.9%). The primary outcome was the occupational falls in the past year. The secondary outcome was fall-related fractures. Participants were categorized as those who never used, those who formerly used, and those who currently used tobacco products; the lattermost were further classified according to the product used. Other behavioral factors included alcohol consumption, sleep duration, physical activity, comorbidities, body mass index, hypnotics/anxiolytic use, and sociodemographic variables. Overall, 7.3% participants reported occupational falls, and 2.8% reported fall-related fractures. Occupational fall incidence was higher for those who currently smoked (IR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.20–1.54), particularly those who exclusively used HTPs (IR: 1.78) and those who used both conventional cigarettes and HTPs (IR: 1.64), than for those who never smoked. Fall-related fractures showed similar trends. Short sleep duration and diabetes were associated with increased fall risk, particularly among younger workers. These findings highlight the significant association between HTP use, lifestyle behaviors, and occupational falls.

Background

Falls are a critical global public health concern, with an estimated 684,000 fall-related deaths and 37.3 million serious nonfatal injuries annually1. Measures to prevent falls are being promoted in the workplace2,3. In Japan, where the workforce is rapidly aging, the increasing incidence of occupational falls among older workers has become a significant occupational safety issue. According to the latest data from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, approximately 36,000 occupational falls resulting in at least 4 days of work absence were reported in 20234.

To address this urgent issue, Japan has primarily focused on mitigating environmental and socioeconomic risks—two of the four major risk categories (biological, behavioral, environmental, and socioeconomic)5. The government has promoted strategies, such as creating fall-preventive environments and educating workers on health and safety6. However, strategies targeting behavioral risks, such as improving individual workers’ lifestyle habits, have received less emphasis, largely owing to a lack of workplace-specific evidence.

Individual lifestyle behaviors, including physical activity, sedentary behaviors, and sleep quality, are associated with the risk of falls in the workplace7,8,9. However, the association between the risk of falls and certain lifestyle factors, such as conventional cigarette smoking or tobacco product use—including the use of new types of tobacco (e.g., heated tobacco products [HTPs], including IQOS and Ploom TECH)—remains poorly understood across all age groups10. Previous studies have suggested that people who smoke tend to experience falls, fractures, and postural instability11,12,13, which indicates that workers who smoke may have a higher risk of occupational falls. Furthermore, nationally representative data on occupational falls, including those not resulting in work absence, are unavailable.

This study determined the incidence of occupational falls among Japanese workers across all age groups using a large-scale nationwide dataset. Additionally, the study examined the association between HTP use and occupational fall incidence, particularly in combination with lifestyle behaviors.

Results

Among the 18,440 current workers, 8,096 were women (43.9%), and 44.3%, 47.5%, and 8.2% were aged 20–39, 40–64, and 65–74 years, respectively. Of the total, 7.3% (n = 1,338) experienced occupational falls in the past year, and background characteristics differed significantly between non-fallers and fallers, except for educational level (Table 1). Among participants who currently used tobacco products across all age groups, exclusive use of conventional cigarettes was the most prevalent, particularly among middle-aged and older workers. Exclusive use of HTPs was the next most common pattern of use in most age groups, although its prevalence remained below 5% overall. Dual use of both conventional cigarettes and HTPs was uncommon across all age groups (Supplementary Table S1). Estimated annual incidences across different types of falls were 3.4% for falls without injuries, 3.8% for falls with any injury, 2.8% for fractures, and 9.9% for near misses (Table 2). Younger individuals were more likely to experience occupational falls.

Individuals who currently used tobacco products showed a significantly higher IR for occupational falls (IR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.20–1.54), with those who exclusively used HTPs and those who use both conventional cigarettes and HTPs exhibiting particularly elevated incidences (IR: 1.78 and 1.64, respectively) (Table 3). Other lifestyle and behavioral factors, including high physical activity levels, extreme sleep durations (0–5 h or ≥ 10 h), comorbidities, habitual use of hypnotics or anxiolytics, and severe WFun scores were also associated with higher incidences of occupational falls.

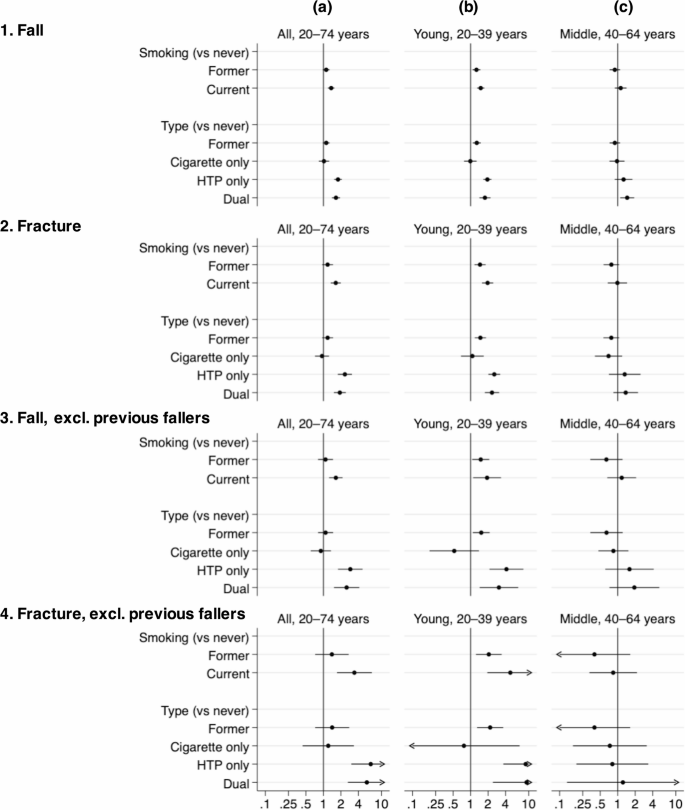

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses, including fall-related fractures, confirmed these patterns (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3), with younger workers (aged 20–39 years) showing the most pronounced associations (Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables S4 and S5).

Incidence ratios of fall and fall-related fracture in each tobacco product use status. The incidence ratios (circles) and 95% CIs (bars) of current tobacco use status/types, compared with never users, in different populations were estimated with two-level multilevel Poisson regression with robust variance. Random intercepts for residential areas (47 prefectures, Level 2 variable) were used. We adjusted for confounding factors (sex, age, educational attainment, occupation class, industry sector, equivalent annual household income, workplace size, and Work Functioning Impairment Scale). Additionally, we accounted for lifestyle and behavioral variables (drinking habits, weekly physical activity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, body mass index, and habitual use of hypnotics or anxiolytics). The samples used in the analysis were as follows: (1) n = 18,440 (1,338 falls and 17,102 non-fallers), (2) n = 17,610 (508 fractures and 17,102 non-fallers), (3) n = 15,470 excluding previous fallers (226 falls and 15,244 non-fallers), and (4) n = 15,300 excluding previous fallers (56 fractures and 15,244 non-fallers). Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HTP, heated tobacco product.

Discussion

In this nationwide, cross-sectional study conducted in Japan, we found that various lifestyle and behavioral factors, including HTP use, were associated with occupational falls in the workplace. Compared with individuals who never used tobacco products, those who currently used them showed a 1.3-fold higher incidence of occupational falls, with the most pronounced increase in incidence (approximately 1.8-fold higher incidence) observed for those who exclusively used HTPs. A similar pattern was observed for falls resulting in fractures, particularly among younger workers. Other lifestyle and behavioral factors, including physical activity, sleep durations, comorbidities, and individual functioning at work, were also associated with occupational falls. These findings highlight the potential importance of lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation, in preventing occupational falls.

In Japan, HTP use has emerged as a public health concern, with approximately 40% individuals currently using tobacco products reportedly using HTPs14; however, evidence on the association between occupational falls, HTP use, and cigarette smoking remains limited, and no previous studies have specifically investigated the impact of HTP use on occupational falls. Epidemiological studies have reported an increased risk of fall-related fractures among individuals currently using tobacco products11. A recent Mendelian randomization study also identified a higher tendency of falling among this population12. People who smoke exhibit lower postural stability than do those who do not use tobacco products13, and nicotine exposure can affect vestibular functions15. However, the biological mechanisms underlying falls associated with the use of conventional combustible cigarettes and HTPs remain unclear. Although nicotine dependence has been suggested to increase the risk of occupational injuries, combustible cigarettes and HTPs are fundamentally different products, and our study was not able to evaluate the exposure to harmful substances emitted by these products. Nevertheless, HTPs may be used more freely regardless of location, such as indoors, outdoors, and designated smoking areas. This difference in usage patterns raises the possibility that HTPs are more frequently used in environments where the fall risk is elevated. Our study did not assess nicotine exposure or the specific locations of tobacco use; thus, these hypotheses remain speculative. Future studies investigating fall incidence in relation to the locations where individuals use tobacco products may help elucidate behavioral mechanisms underlying falls among workers who use these products.

In our study, individual comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, medication use (e.g., hypnotics or anxiolytics), high levels of physical activity, and short sleep duration were associated with higher incidences of occupational falls, which is consistent with findings from previous studies9,16,17,18. Additionally, we found that individual functional ability at work was linked to occupational falls. While occupational safety efforts should primarily focus on mitigating environmental risks, addressing lifestyle and behavioral risks may also play a crucial role in preventing occupational falls.

A notable finding in our study is that even among younger workers, tobacco product use, particularly HTP use, was associated with occupational falls and fall-related fractures. Interestingly, more than half of the occupational falls observed in our study occurred in this younger age group. Although fall prevention strategies have traditionally focused on older individuals considered to be at higher risk4, the incidence of falls across different age groups, particularly among younger workers, has not been fully elucidated. Our findings emphasize the importance of addressing occupational falls among younger workers. Younger workers may be assigned to workplaces with a higher risk of occupational falls; therefore, the role of age and occupational setting should be carefully considered. Workplace fall prevention strategies should also target relatively younger age groups. Hence, encouraging healthy lifestyle behaviors may play a critical role in reducing falls, potentially acting as a nudge effect. Nudging techniques influence individuals to make certain choices, such as adopting healthier behaviors, by leveraging factors such as risk and loss aversion19. Various nudging strategies for smoking cessation exist, including company-wide no-smoking declarations by organizational leaders, which could also be applied in workplace settings.

Our study had some limitations. First, as this was a self-reported, cross-sectional study, causal inferences could not be established. Additionally, detailed information on tobacco use behaviors—such as usage intensity, duration of use, and abstinence period—was not available. Further longitudinal studies are warranted to investigate the mechanisms and temporal relationship between conventional cigarette smoking/HTP use and fall incidence. Second, recall and reporting bias of HTP use could not be discarded, as suggested in a study on combustible cigarette smoking and electronic cigarette use20. Moreover, tobacco product types may have been potentially misclassified. For example, we could not identify participants who had transitioned from conventional cigarettes to HTPs, and this may have resulted in underestimation of fall risks associated with combustible cigarette use. Among individuals who use tobacco products, a growing perception that HTPs are healthier alternatives may lead to switching or dual use. Such misconceptions may have introduced a healthy user bias and influenced self-reports of HTP use. Third, although sensitivity analyses demonstrated similar patterns, the data on falls were self-reported, which may have introduced underestimation or misclassification. Fourth, unmeasured confounding factors may have existed. However, our findings appeared relatively robust. For example, the E-value for the fully adjusted IR for occupational falls among participants who currently used tobacco products was 2.06. Similarly, the E-values were 2.96 for participants who used HTPs and 2.66 for those who used both conventional cigarettes and HTPs; these values indicated that comparably strong, unmeasured confounding would be necessary to nullify these associations21.

Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this nationwide study is the first to specify the incidence of occupational falls by tobacco product type and to reveal the association between HTP use and other behavioral factors, and occupational falls in Japan. Although the impacts of tobacco product use on various health outcomes are widely established, greater attention should be paid to occupational falls among individuals currently using tobacco products, regardless of tobacco type, from the perspective of occupational safety.

In conclusion, occupational falls may occur across all age groups, and various lifestyle behaviors, particularly HTP use, may be associated with occupational falls. To better understand the observed associations, further studies are needed to identify the mechanisms by which tobacco product use and lifestyle behaviors contribute to the increased incidence of occupational falls in the aging society.

Methods

Study design, data setting, and participants

This nationwide cross-sectional study utilized data from the Japan COVID-19 and Society Internet Survey (JACSIS) (https://jacsis-study.jp/). The JACSIS dataset was derived from a panel of approximately 2.3 million individuals across all 47 prefectures in Japan, maintained by Rakuten Insight, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Details regarding the JACSIS, including quality controls, national representativeness, and panelist policies, have been published previously22,23. Data collection occurred between September and November 2023.

Initially, 25,332 participants aged 20–74 years were included. Of them, 6,892 individuals who were not actively employed (e.g., homemakers, students, and unemployed individuals) were excluded. The final analytical sample comprised 18,440 current workers (mean age ± standard deviation, 43 ± 14.3 years).

Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants before they completed the internet-based questionnaire. This study adhered to the guidelines of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (No. R4-054).

Outcome measurement: occupational falls

The primary outcome was the occurrence of workplace falls over the past year. Participants responded to the question, “Have you experienced a fall while at work in the past year?” with the following options:

-

1.

Experienced a fall for the first time in the past 2 months,

-

2.

Experienced a fall for the first time in the past year,

-

3.

Experienced a fall in the past year but not for the first time,

-

4.

Did not experience a fall in the past year but had experienced one more than a year ago,

-

5.

Never experienced a fall.

For the primary analyses, participants who selected options 1, 2, or 3 were categorized as having experienced a fall (“fallers”), whereas those who selected options 4 or 5 were categorized as “non-fallers.” These two groups were mutually exclusive. In addition, to explore the potential influence of fall history on fall risk, we identified “previous fallers” as participants who selected options 3 or 4, i.e., those with any history of falling more than 1 year ago. Falls during commuting were excluded to focus exclusively on workplace falls.

As the secondary outcome, fall-related fractures were identified by asking, “Have there been days when you were unable to work due to a fracture caused by a fall at work?” Individuals who experienced a fall without a fracture were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, supplementary data were collected on falls without injuries, falls with any type of injury, and near misses (almost fell).

Exposure: tobacco product uses and other covariates, including lifestyle behavioral factors

Based on tobacco use status, participants were categorized as those who never used, those who formerly used, and those who currently used tobacco products. Participants who formerly used tobacco products were defined as individuals who had used either conventional cigarettes or HTPs at least once, but had quit by the time of study initiation. Participants who currently used tobacco products were further classified into those who exclusively used conventional cigarettes, those who exclusively used HTPs, and those who used both conventional cigarettes and HTPs (dual use). Available HTP brands during the study included Ploom Tech, Ploom X, IQOS, glo, and lil HYBRID22,24,25.

Other lifestyle behavioral factors included drinking habits (none, < 2 drinks/day, and ≥ 2 drinks/day; e.g., beer, Japanese sake, shochu, wine, and whisky), sleep duration (0–5 h, 6–9 h, ≥ 10 h, and unknown), and physical activity level (low, moderate, and high) based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF)26. Additional covariates included comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes), body mass index, and habitual use of hypnotics or anxiolytics.

Confounders included age, sex, educational level (≤ 12 years [high school] or ≥ 13 years [college or university]), occupation class and industry sector, equivalent annual household income (< 1.5 million JPY [approximately 15,000 USD], ≥ 1.5 million JPY, and unknown), and workplace size (≤ 49 workers, 50–999 workers, ≥ 1,000 workers, and unknown). Moreover, to assess the ability of individuals to function at work, the Work Functioning Impairment Scale (WFun) was utilized27.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were compared using the t-test for continuous variables or the Chi-square test for categorical variables. Incidence ratios (IRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for workplace falls were calculated using multilevel Poisson regression with robust variance, accounting for clustering within prefectures. All analyses were adjusted for confounders (Model 1). In Model 2, tobacco use status was further adjusted for all other behavioral factors. In Model 3, specific tobacco product types were included and adjusted for all other behavioral factors. Additionally, age-specific analyses were conducted for participants aged 15–39 years and 40–64 years; analyses for those aged 65–74 years were excluded due to insufficient outcomes.

For sensitivity analyses, we examined IRs for fall-related fractures. Additionally, we analyzed IRs after excluding previous fallers, given their high risk of recurrence as indicated by prior data (PR: 23.3, 95% CI: 20.4–26.6). Furthermore, to account for differences in tobacco use status and tobacco product type, we conducted multilevel Poisson regression analyses with robust variance adjusted for 5-year age categories. We also compared the associations within 10-year age strata from 20 to 59 years, excluding participants aged 60–74 years because of an insufficient number of outcomes. The alpha level was set at 0.05, and all p-values were two-sided. Data were analyzed using STATA/SE 18.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are restricted due to personal identification and privacy concerns. The research data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

-

World Health Organization. (Falls). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls

-

Chaumont Menendez, C., Castillo, D., Rosenman, K., Harrison, R. & Hendricks, S. Evaluation of a nationally funded state-based programme to reduce fatal occupational injuries. Occup. Environ. Med. 69, 810–814 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Wah, W., Berecki-Gisolf, J. & Walker-Bone, K. Epidemiology of work-related fall injuries resulting in hospitalisation: Individual and work risk factors and severity. Occup. Environ. Med. 81, 66–73 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Ministry of Health. Labour and Welfare. Industrial accident situation in 2023. article in Japanese. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_40395.html

-

World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on Falls Prevention in Older Age. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563536

-

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The 14th occupational safety & health program. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11200000/001253683.pdf

-

Sherrington, C. et al. Evidence on physical activity and falls prevention for people aged 65 + years: systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17, 144 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Watanabe, K. et al. Daily walking habits can mitigate age-related decline in static balance: A longitudinal study among aircraft assemblers. Sci. Rep. 15, 2207 (2025).

Google Scholar

-

Alhainen, M. et al. Sleep duration and sleep difficulties as predictors of occupational injuries: A cohort study. Occup. Environ. Med. 79, 224–232 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Hori, A., Tabuchi, T. & Kunugita, N. Rapid increase in heated tobacco product (HTP) use from 2015 to 2019: From the Japan society and new tobacco internet survey (JASTIS). Tob. Control. 30, 474–475 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Liu, S. et al. Incidence and risk factors for foot fractures in china: A retrospective population-based survey. PLOS One. 13, e0209740 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Guo, X., Tang, P., Zhang, L. & Li, R. Tobacco and alcohol consumption and the risk of frailty and falling: A Mendelian randomisation study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 77, 349–354 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Iki, M., Ishizaki, H., Aalto, H., Starck, J. & Pyykkö, I. Smoking habits and postural stability. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 15, 124–128 (1994).

Google Scholar

-

Ministry of Health. Labour and Welfare. National health and nutrition survey in 2023. article in Japanese. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/001338334.pdf

-

Pereira, C. B., Strupp, M., Holzleitner, T. & Brandt, T. Smoking and balance: Correlation of nicotine-induced nystagmus and postural body sway. NeuroReport 12, 1223–1226 (2001).

Google Scholar

-

Xu, Q., Ou, X. & Li, J. The risk of falls among the aging population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public. Health. 10, 902599 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Gravesande, J. & Richardson, J. Identifying non-pharmacological risk factors for falling in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 39, 1459–1465 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Feskanich, D., Willett, W. & Colditz, G. Walking and leisure-time activity and risk of hip fracture in postmenopausal women. JAMA 288, 2300–2306 (2002).

Google Scholar

-

Fakir, A. M. S. & Bharati, T. Healthy, nudged, and wise: Experimental evidence on the role of information salience in reducing tobacco intake. Health Econ. 31, 1129–1166 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Gottschlich, A., Mus, S., Monzon, J. C., Thrasher, J. F. & Barnoya, J. Cross-sectional study on the awareness, susceptibility and use of heated tobacco products among adolescents in Guatemala city, Guatemala. BMJ Open. 10, e039792 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Haneuse, S., VanderWeele, T. J. & Arterburn, D. Using the E-Value to assess the potential effect of unmeasured confounding in observational studies. JAMA 321, 602–603 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Zaitsu, M. et al. Maternal heated tobacco product use during pregnancy and allergy in offspring. Allergy 78, 1104–1112 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Koga, C., Tsuji, T., Hanazato, M., Nakagomi, A. & Tabuchi, T. Intergenerational chain of violence, adverse childhood experiences, and elder abuse perpetration. JAMA Netw. Open. 7, e2436150 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Zaitsu, M. et al. Heated tobacco product use and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and low birth weight: analysis of a cross-sectional, web-based survey in Japan. BMJ Open. 11, e052976 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Hosokawa, Y. et al. Association between heated tobacco product use during pregnancy and fetal growth in japan: A nationwide web-based survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 11826 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 1381–1395 (2003).

Google Scholar

-

Fujino, Y. et al. Development and validity of a work functioning impairment scale based on the Rasch model among Japanese workers. J. Occup. Health. 57, 521–531 (2015).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. A preprint version of this manuscript is publicly available on medRxiv at https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.16.25321430.

Funding

This study was partly supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (23EA1003, 23FA1004, 23JA1003, and 23JA1004); UOEH Grant-in-Aid for Collaborative Research between the Institute of Industrial Ecological Sciences and the University Hospital (2022-1) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI JP22K17401).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ST, KW, and MZ designed the study. MZ supervised the study. ST, KW, and MZ developed the methodology. ST, TT, and MZ created the dataset. ST and MZ analyzed the data. ST, KW, and MZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SH, TY, YF, and TT commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Fujino holds the copyright to WFun with royalties paid from Sompo Health Support Inc., outside of this work. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (no. R4-054).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsushima, S., Watanabe, K., Hirohashi, S. et al. Occupational fall incidence associated with heated tobacco product use and lifestyle behaviors in Japan.

Sci Rep 15, 20035 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05204-9

-

Received: 24 February 2025

-

Accepted: 02 June 2025

-

Published: 06 June 2025

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05204-9

Keywords

- Bone fractures

- Heated tobacco product

- Occupational falls

- Smoking

- Workplace