Prince Edward Island’s ombudsperson is now investigating the province’s mobile mental health services, after a committee of MLAs grew concerned about how a lack of co-ordination may have contributed to the death of Tyler Knockwood.

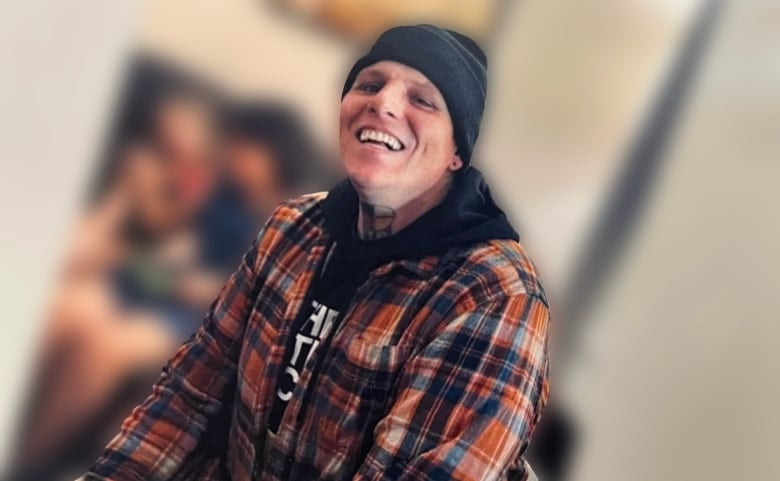

The 34-year-old was having a mental health crisis when he took his own life in January. His family’s repeated calls for help brought Charlottetown police officers to their home, but not one of P.E.I.’s specialized units.

The province’s Standing Committee on Health and Social Development was told the Island’s mobile mental health unit was not called due to “a failure in communication, which resulted in the death of an Islander,” according to an Oct. 19 letter chair Susie Dillon sent to ombudsperson Sandy Hermiston.

“The mobile mental health unit did not know of the mental health crisis until after the fact,” Dillon wrote. “It appears that no changes or reviews of the program and dispatch process have been done.”

In an interview with CBC News Friday, Hermiston stressed that her team won’t be looking into the circumstances in the hours leading up to Knockwood’s death.

“There was a complaint made about the way the Charlottetown police handled the matter. That complaint is processed under a completely different piece of legislation and a completely different process,” she said. “Summerside police have been assigned that matter so I will not be looking into that; that is not my jurisdiction.

“There is no point in another body looking at the same question, so we will be really focusing on mobile mental health.”

Hermiston said she doesn’t have an estimate of how long her office’s investigation will take.

As the MLAs were hearing from witnesses on Oct. 18, they became convinced that the lack of a centralized dispatch system for the mobile mental health program needs to be fixed immediately.

Currently, anyone needing to access a mobile mental health unit directly has to call 1-833-553-6983. There is also the option to call 811 or 911, and a dispatcher could potentially call the unit.

But Charlottetown Police Services has its own dispatcher, and it’s up to the officers assigned to a complaint or a call for help to contact the mobile mental health unit.

The committee heard that Charlottetown police did not call the unit last January, when Knockwood’s family asked for help dealing with his “extreme paranoia,” which seemed to be getting worse.

An assistant deputy minister with the Department of Health and Wellness agreed a centralized dispatch system for all emergency calls could improve efficiency.

“It is unfortunate that the systems aren’t talking to each other and calls aren’t being redirected to the mobile mental health line,” Deborah Bradley told the MLAs. “I agree that we need to find solutions so that there is a seamless transition for the calls to be made.”

When the mobile mental health service was launched two years ago, one of the goals was to switch the handling of some wellness checks from police to mental health professionals, including a paramedic and a clinician specializing in social work.