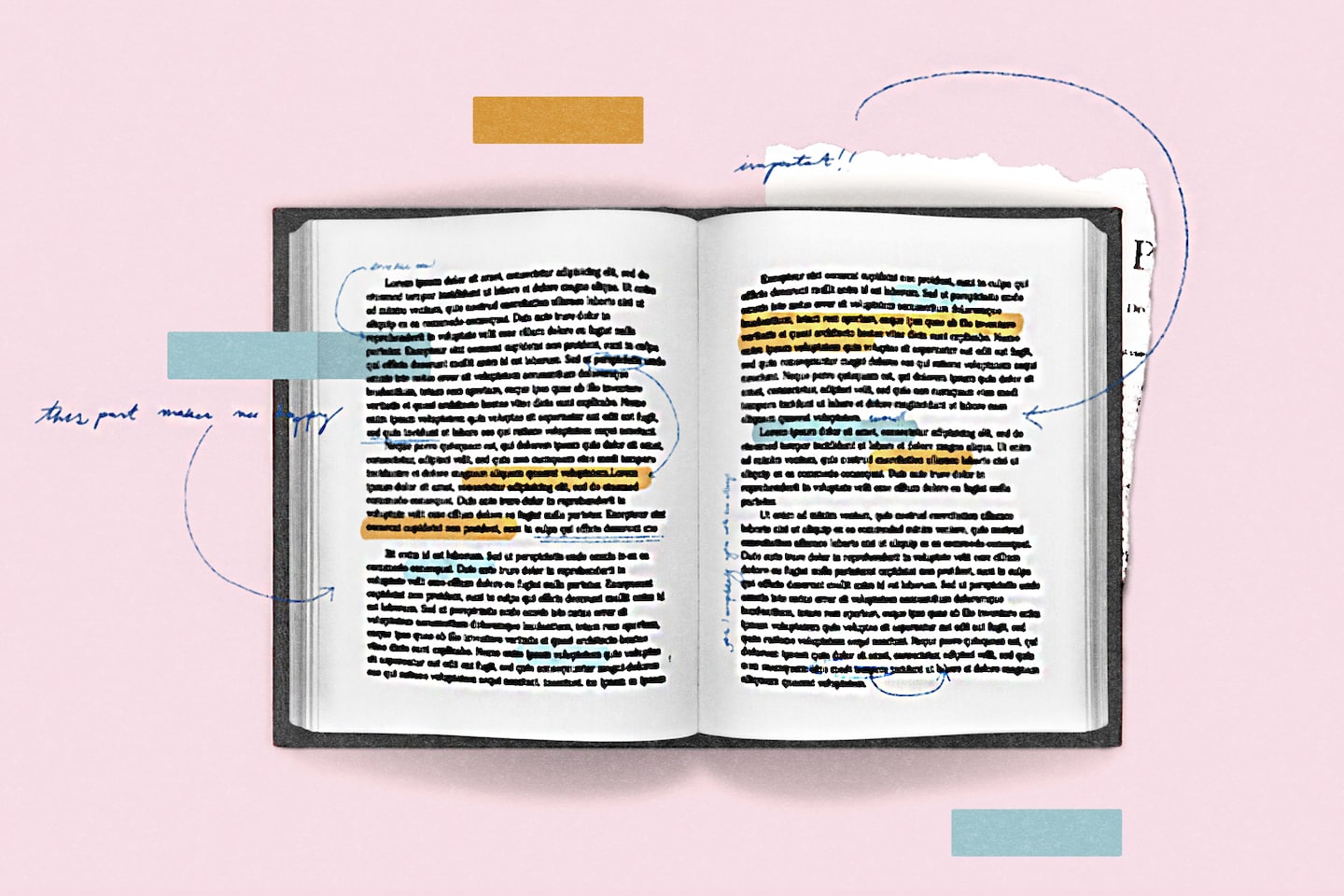

Eboni Thompson’s Instagram isn’t just an ode to the classic literature that she loves. It’s also a celebration of annotation: Warmly lit video reels linger on the colorful tabs that fringe the edges of her Penguin Classics, the ruler-straight lines highlighting important passages and the margins where neat handwriting frames each page.

Annotations have traditionally been the domain of academics, used to add commentary, feedback and criticism to texts. Annotation is “elemental to scholarship,” according to Remi Kalir and Antero Garcia, who literally wrote the book on annotation (“Annotation,” MIT Press). As a reminder of the high-minded history of marginalia, they note that Milton annotated Shakespeare.

But now the practice is attracting a broader audience of hobbyists. Thompson is part of a cadre of book influencers who not only share what they’re reading but how they’re reading — the underlined quotes they love, the paragraphs that stand out and the themes that resonate. As Berlin-based creator candlelitchapters wrote on Instagram, book tabs “serve as navigational beacons,” and markers “add a touch of individuality.” Thompson annotates classic literature almost exclusively; her latest conquest was “Dracula,” and her snapshots were cozily staged with mugs of coffee, pumpkins and flickering candles. Others, however, annotate a range of genres, marking up literary fiction by Donna Tartt or tear-jerking romance by Colleen Hoover or the fantastical bestseller “Fourth Wing.”

After college, Thompson started annotating because she missed the feeling of analyzing texts and taking notes. One day, she went to the bookstore and bought “Sense and Sensibility,” by Jane Austen, and as she started reading, she realized how much she wanted to remember about the book after she was finished. “It wasn’t as intense or as thorough as I do now,” she said of her early annotations. “It was mostly just little quotes here and there, maybe a word I had never known before, a star next to it, or an idea that I was like, ‘Oh, I want to come back to that.’” Thompson began chronicling her annotations on Instagram and TikTok where she now has paid partnerships.

Thompson, a stay-at-home mother to two young children, recently finished reading and annotating “The Hunchback of Notre Dame,” a book she said she was glad she read carefully. Annotating slows down her reading process, but the output is worth it: “I feel like I take away so much more from these stories, and by the end of it, I feel like I have a connection with what the author has written,” she said.

In October, I was inspired by Thompson’s Instagram account to annotate a secondhand copy of “Frankenstein.” To prepare, I gathered some colorful pens, bought some expensive Japanese sticky notes and grabbed a fresh highlighter.

It had been a long time since I had annotated a book — specifically since high school, when I read “Crime and Punishment.” Years later, when my sister asked to borrow my copy, I had forgotten about my adolescent notes. Halfway through reading it, she playfully teased me about my shameful marginalia, wondering why I had bothered underlining “sultry” — a word I had surely known in 11th grade — and writing the definition, “hot or humid,” in the margin. I chalked it up to trying to look busy during class.

Determined to outdo my 16-year-old self, I placed sticky notes as obvious themes emerged: a red note for a nice quote about friendship, a yellow one for a beautiful description of a storm over the Swiss Alps. But in the margins I jotted down little meaningless words. In one passage, Elizabeth Lavenza relays some information about various neighbors in Geneva in a letter to Victor Frankenstein. (To paraphrase: The pretty Miss Mansfield is getting married to a young Englishman while her ugly sister, Manon, married a rich banker.) I wrote “Ok, gossip!” next to the paragraph.

Many of my observations were painfully obvious: After Victor has his first mental breakdown and his friend Henry Clerval comes to care for him, I wrote at the end of the chapter, “Victor has good friends and a good support system. Making a monster was entirely unnecessary … ”

While my annotations were silly, I found myself going back to places I had marked. A sentence, next to which I had written “GRIEF” caught my eye: “ … survivors are the greatest sufferers and for them time is the only consolation.” During my reading of “Frankenstein,” I was experiencing acute grief, a well-known theme throughout the novel, after a summer marked by loss. I was grateful that past-me marked that passage to revisit at a time when I might need those comforting words.

I soon realized that there is no shortage of annotated classics that offer a glimpse at how the pros do it. I recently read “The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway,” a beautifully illustrated edition with an introduction and annotations by Merve Emre, as well as photos, newspaper clippings and other historical information. I probably would’ve skimmed smaller details, like what a “despatch box” is, if I were reading a non-annotated version. More extensive notes from Virginia Woolf’s diaries illuminate what the author was thinking, feeling and experiencing at the time she wrote her masterpiece.

During my reading and annotating of “Frankenstein,” I slowed down and engaged with the story in a way I might not have had I been reading at my usual clip. Annotating feels a bit like homework — an assignment you give yourself that allows you to use special pens and highlighters, colored sticky notes and whatever squiggles and doodles you desire. Maybe it’s not scholarship in the traditional sense, but it’s studious, nonetheless.