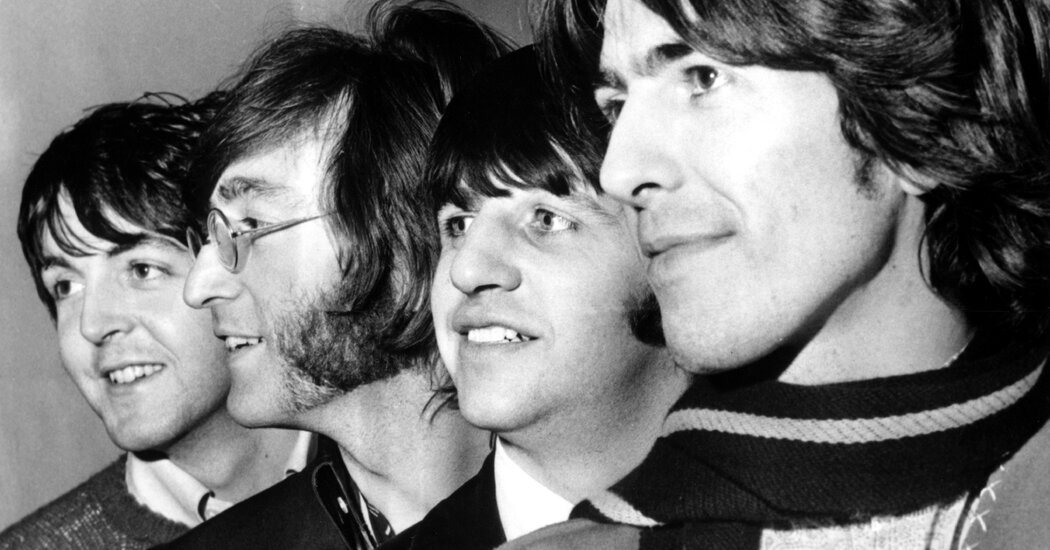

Sixty-one years after releasing their first single, “Love Me Do,” the Beatles have released their last. “Now and Then” mirrors, in the three beats of its title, its antecedent, which is on the other side. The single accompanies a new version of the group’s Red and Blue greatest hits albums.

It may be considered a cynical marketing ploy, but the story of its long gestation suggests otherwise. Inside the story of “Love Me Do” to “Now and Then” is the love story of John Lennon and Paul McCartney — which is our story, too.

Over a half a century since the Beatles split up, their songs still permeate our lives. We sing them in nurseries and in stadiums; we cry to them at weddings and funerals, and in the privacy of our bedrooms. The appeal is multigenerational; Taylor Swift and Billie Eilish are avowed fans.

Beatles songs still speak to us so directly because they are vehicles for the transmission of feelings too powerful for normal speech. Mr. Lennon and Mr. McCartney were intense young men who grew up in an era before men were encouraged to speak about their feelings, either in therapy or to one another. They gained their emotional education from music, especially the music of Black artists like Smokey Robinson, Arthur Alexander and the Shirelles. Almost everything they felt — and they felt a lot — was poured into music, including their feelings about each other.

“Now and Then” was not intended as a Beatles song. Well after the band’s breakup, Mr. Lennon wrote it at the piano sometime during his retreat from the public eye in the late 1970s. It was recorded on a tape machine and squirreled away. In 1994, his wife, Yoko Ono, uncovered a pair of cassettes of her husband’s demos and contributed them to the Beatles retrospective project “Anthology.” On the label of one, Mr. Lennon had scrawled “Now + Then,” as if to make a note of that song in particular. But because the sound quality was very poor (George Harrison called it “rubbish”), “Now and Then” didn’t get far.

But Mr. McCartney never forgot about it. He sent the demo to Peter Jackson, the director of the Beatles documentary “Get Back,” who used cutting-edge audio technology to clean the tape so thoroughly that it sounded as if Mr. Lennon was back in the room.

“There it was, John’s voice, crystal clear,” Mr. McCartney said. “It’s quite emotional.” Mr. McCartney and Ringo Starr, now in their 80s — and George Harrison, posthumously — added parts.

Why did Mr. McCartney pursue this project for so long? He is busy enough, having worked on solo albums, a memoir, a stage musical and a global tour in the past five years alone. “Now and Then” is a sweetly melancholy song, but perhaps not at the level of the Beatles when they were together. Giles Martin, producer of this new track and son of the legendary Beatles producer George Martin, has a theory: “I do feel as though ‘Now and Then’ is a love letter to Paul written by John,” he said, and believes “that’s why Paul was so determined to finish it.”

Although it has been variously framed as a friendship, a rivalry or a partnership of convenience, the best way to think about the relationship between these two geniuses is as a love affair. As far as we know, it wasn’t a sexual relationship, but it was a passionate one: intense, tender and tempestuous.

Mr. Lennon and Mr. McCartney met as teenagers in 1957. They were gifted, charismatic and damaged. Mr. McCartney had recently lost his beloved mother to cancer; Mr. Lennon had been passed around from mother to father to aunt without ever feeling wanted. His mother, Julia, whom he adored, was killed by a careless driver the year after.

Bereavement bound these motherless boys together, and laughter, too. But music was the strongest binding force of all. They decided to write songs with each other, a promise they mostly kept until the Beatles split, and dreamed a whole private world into being.

Within a few years, the world became their dream. The micro-culture that germinated between them became the ethos of the Beatles, which left an enduring imprint on all of us. We might not be as optimistic as they were then, but we are imbued with their relentless curiosity, wild imagination and belief in the possibilities of love.

Throughout their relationship, Mr. Lennon and Mr. McCartney used songs to tell each other things they probably didn’t feel able to say face to face. Mr. Lennon said he wrote the 1968 song “Glass Onion” (“the walrus was Paul”) as a way of letting Mr. McCartney know they were still friends. After the band’s breakup, they maintained a dialogue at a distance, in songs full of recrimination, regret and affection. Stung by the barbs that Mr. McCartney had embedded on his album “Ram” (“You took your lucky break and broke it in two”), Mr. Lennon recorded “How Do You Sleep?,” a spiteful, excoriating attack on his former songwriting partner (“the only thing you done was yesterday”). Mr. McCartney responded with “Dear Friend,” a wistful call for an end to hostilities (“Is this really the borderline?”).

After this, a truce was called. For the rest of the decade, until Mr. Lennon’s death, in 1980, they made halting efforts to re-establish their friendship from different sides of the Atlantic. Mr. McCartney and his wife, Linda, visited Mr. Lennon in America, but they may still have saved their true heart-to-hearts for songs. In “Let Me Roll It,” Mr. McCartney performs a virtual Lennon impression. In “I Know (I Know),” Mr. Lennon sings, “Today, I love you more than yesterday,” over a riff based on their last direct songwriting collaboration, “I’ve Got a Feeling.”

“Talking is the slowest form of communicating,” John Lennon said in 1968. “Music is much better.” In a sense, the music of the Beatles, which brings so much joy and consolation, is the glorious fruit of male repression. We like to think we live in a more emotionally enlightened age. We have learned to talk it out. Yet sometimes I think that is itself a kind of avoidance, or a failure of nerve. We’ve awakened from the dream, and yet seem to be more confused than ever.

Carl Perkins, the rockabilly guitarist and singer, and a hero to the Beatles, collaborated with Mr. McCartney in the wake of Mr. Lennon’s death. One day, he played Mr. McCartney a song he had written for him with the line, “My old friend, won’t you think about me every now and then?” At this, Mr. McCartney teared up and left the room, leaving Linda to reassure a startled Mr. Perkins. “She said [those were] the last words that John Lennon said to Paul in the hallway of the Dakota building,” he told Goldmine magazine toward the end of his life. Mr. Lennon “patted him on the shoulder, and said, ‘Think about me every now and then, old friend.’”

We can see why a song called “Now and Then” might be so important to Mr. McCartney, and we can guess what he hears in Mr. Lennon’s lyrics:

If we must start again / Well we will know for sure /That I will love you … / Now and then, I miss you / Now and then

/ I want you to be there for me.

On those last two lines, we can hear Mr. McCartney’s aged voice joining that of his old friend.

Last year I was in the audience at the MetLife Stadium in New Jersey for a McCartney show. The first encore of the set was a virtual duet with Mr. Lennon on “I’ve Got a Feeling,” using footage of the 1969 rooftop concert.

It could have felt cheap, a gimmick, but as Mr. McCartney turned toward the giant image of his friend as a young man, I cried, along with thousands of others.

Technology can revive the dream state, if only for the length of a song.

Ian Leslie writes the newsletter The Ruffian and is the author of, most recently, the book “Conflicted: How Productive Disagreements Lead to Better Outcomes.” He is writing a book, “John and Paul: A Love Story in Songs,” about the relationship between John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.