A crisis counselor, a fitness coach and a caregiver for the elderly walked into an Anchorage bar. They transformed into a deacon, an unhinged yoga instructor and a fighting stripper. Everyone beat everyone up.

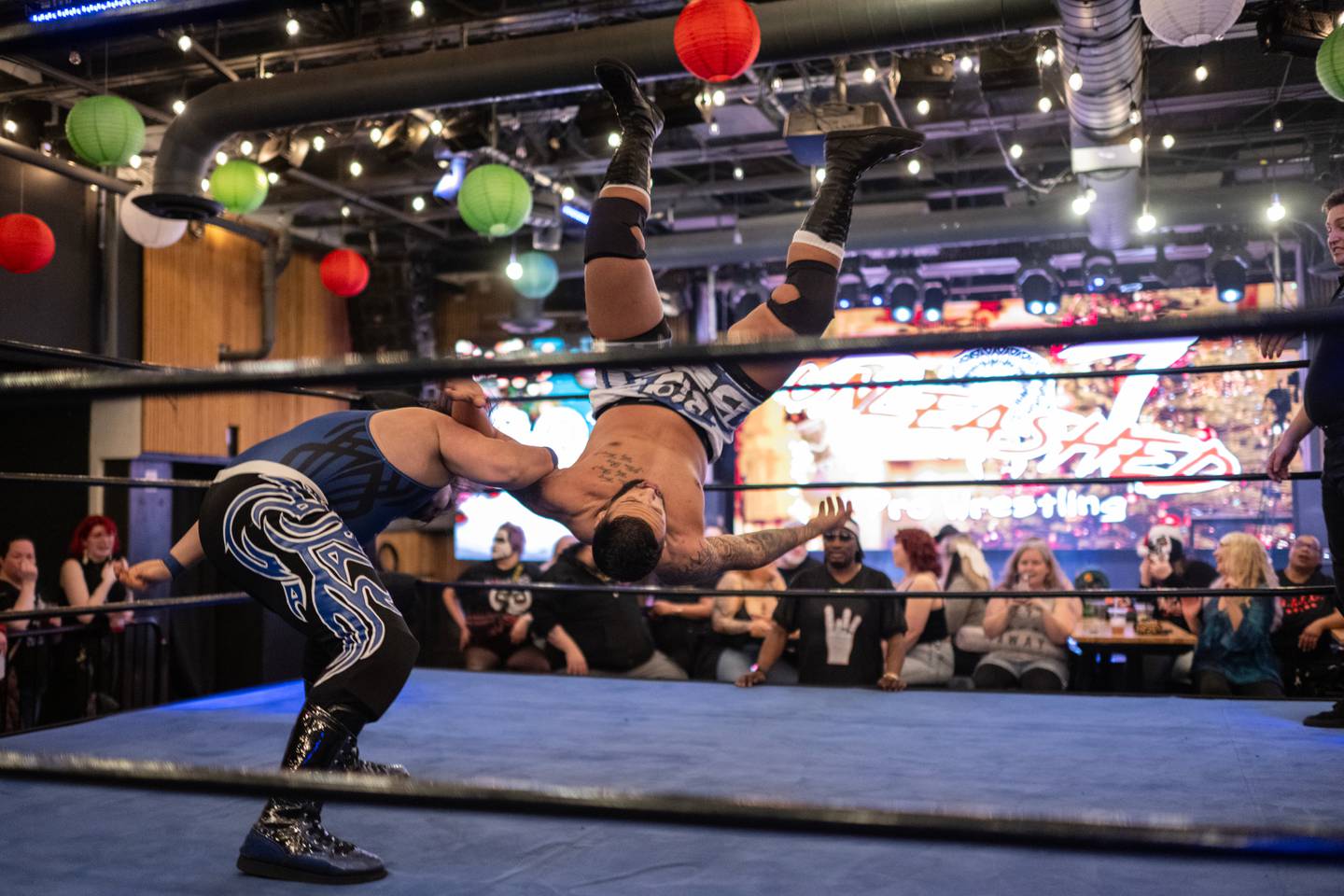

The controlled mayhem of professional wrestling drew a rowdy crowd to Williwaw Social on a Thursday night earlier this month. Performers donned face paint, capes and costumes. The bad guys menaced and scowled at an audience that laughed and heckled back. The wrestlers soared, collided, flipped and body-slammed each other, theatrically but athletically, for seven matches as the spectators howled, booed, cheered and drank.

Anchorage’s 907 Pro Wrestling stays true to the off-the-wall roots of “professional wrestling,” a term used to distinguish wrestling, the scripted exhibition of high-flying showmanship, from wrestling, the actual sports competition with rules. Lately, 907’s troupe of performers and students are finding an uptick in demand for their old-school brand of entertainment. Owner Justin Holt calls it “live-action theater,” part stunt show and part magic show.

“We’re just constantly trying to improve to make it look better,” said Holt.

907 is pinning down its biggest year yet. By the end of December, the company will have produced 41 shows, more than double last year’s output. That includes two monthly shows — a family-friendly Saturday afternoon event at the Arctic Rec Center and a spicier “Unleashed” showcase at Williwaw for the 21-and-up crowd. It also includes a couple shows at the Alaska State Fair that drew its biggest audiences to date in August.

“I’m seeing new faces constantly,” Holt said.

There are currently no other pro wrestling outfits like 907 in Alaska, Holt said, though others have come and gone over the years. He speaks highly of the character development and storytelling showcased by Fairbanks Ladies of Wrestling, but FLOW places less emphasis on wrestling maneuvers and hosts far fewer shows, he said.

Holt, who is better known by his performer name, J.T. West, launched the company in 2019 as a “wrestling academy” to train wrestlers. But he said he couldn’t resist the pull of producing shows for live audiences. Holt came to Alaska in 2012, toward the end of his own 15-year career in the ring. This is his second run at operating a wrestling school and show production company in Alaska. He was a partner in New Frontier Wrestling Alliance, based in Wasilla, which held events for two years before a fire destroyed the building it used in 2015.

ADVERTISEMENT

“This is one of those things that just gets in your blood and you can’t get rid of it,” he said.

After a yearlong pandemic-related delay, 907 Pro Wrestling put on its first show in June 2021. It started small — only three of its wrestlers had match experience in front of a crowd then — but attendance proved encouraging. Nowadays, 907 regularly draws 100 to 200 people, Holt said. About 60 loyal customers come to both regular monthly shows. “Alaska is so starved for entertainment,” he said from his Midtown training headquarters in summer.

On his desk lay two gleaming new championship belts. Nearby, mangled folding chairs and smashed garbage cans were stored in a heap. Revenue comes from show ticket sales, tuition for the wrestling school and occasional private events. Wrestlers are paid to perform, but Holt is the only full-time 907 employee.

“We’re currently where we’re able to sustain things. That’s not where I want to be,” Holt said this month. “I would love for this to be something where people could actually make a living.”

Wrestling school

Holt said he can be a perfectionist for the details that make wrestling entertaining. “I want to make sure that when the people come in and see a show, that there’s something for them to go, ‘I want to come back next month.’”

Long gone are the days where performers had to keep up appearances that the action is unscripted. But Holt bristles at the word “fake.” The athleticism, focus, training and daredevil spirit required are quite real, he said.

“We have to make it look like we’re trying to take the guy’s head off without actually doing it,” he said. “And I will argue with anybody until I’m blue in the face that that’s a lot harder than just throwing a right hook.”

In Anchorage, Holt is passing along what he learned from years spent doing gigs with regional wrestling companies, most of which he drove to from his home in West Memphis, Arkansas. His J.T. West persona was “cheap and underhanded.” As a performer, Holt had occasional appearances with national wrestling companies, but there were also times it was tough to stay afloat in the minor leagues. Being a full-time wrestler often involved road-tripping to several cities a week. When he returned home, he’d sleep for a day, he said.

“There were times it was good, but there were times it was absolutely one of the dumbest things I could’ve done,” he said.

Holt came to Alaska in 2012 to escape the humidity of the South and because his wife had roots here. He soon saw a wrestling hole he could fill and met performers who had ambitions he recognized. “I took on trying to help train the guys that were here, because none of them were really trained,” he said.

At his “academy,” in a warehouse-style Midtown space that previously housed an auto detailing shop, he focuses on teaching performers to make the beatdowns look convincing and keep them unbroken. “The moves themselves, I make sure these guys know how to do properly and safely before we allow them to execute it,” he said.

The company currently has about 25 performers and students, Holt said. Wrestlers come to him from a variety of backgrounds and day jobs. Most, not all, have been men. Some clients miss the camaraderie of sports they once played. Some are living out a childhood dream. A few want to build a career and gain national television opportunities Outside.

ADVERTISEMENT

During a training class in June, veteran performers mixed with rookies taking their first “bumps” in the ring. Standing in the middle of the ring, Holt explained that taking a body slam is like doing a jumping cartwheel, then they rehearsed the move. Attention to the small details make for a convincing performance, Holt told the group.

“We want them to forget for a moment that they’re watching a show,” he said. “We want them to get caught up.”

When the lesson was over, Bradley Brown, 26, a wrestling newcomer, said it was harder than he was expecting. “It definitely takes a bitter toll on the body … I’m feeling it,” he said.

He was also surprised how much the training concerned safety.

“There’s so much you do to protect people, it’s pretty cool,” he said.

Showtime

Brown stuck with it. In the months that followed, he learned enough to be part of two tag-team matches. At Williwaw earlier this month, he dressed in camouflage pants and folded his hands for a moment of calm before he burst through the curtain as he was introduced to the crowd as Brad Lee. He took a loss in his first one-on-one match.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I’ve gotten way further than I thought I would ever go,” said Brown, who works at an Anchorage ice cream shop.

It was the deacon who stirred up trouble to get the crowd heated up. That’s Nathan Faehl, whose career as a Religious Affairs Airman for the Air Force involves crisis counseling. Wrestling has been his passion since he was 3, he said as he laced up his boots in the Williwaw dressing room.

Faehl emerged onstage as Deacon Christopher, part of a trio of wrestlers known collectively as The Inquisition. Faehl’s tag-team partner that night was Brother Charles (Charles Fezatte, a firefighter), whose stole read “repent” and “convert.” Boos rained down on the men of the cloth — spandex ablaze with hellfire graphics.

“Shut your mouth!” the deacon scolded an antagonist from the ringside.

In a basement-level hallway, Holt gave notes to a few performers after their matches, urging them to tune in to the audience reaction and end matches on a peak of enthusiasm.

Sweat beaded on Tyler Tinker’s black eye paint. He caught his breath as he listened to Holt. Tinker, a strength and conditioning coach by day, is also a 15-year veteran of pro wrestling, mostly in the Northeast U.S. Before that, he was a kid who built a wrestling ring in his backyard out of a trampoline and garden hoses.

ADVERTISEMENT

Tinker said the latest incarnation of his “Tyler Payne” wrestling persona — a yogi with a dark and dangerous disposition and a frightening mask — is partly inspired by horror and thriller movies he likes. There’s no drug better than the adrenaline rush that comes with pro wrestling, he said.

“What other job in the world do you have entrance music?” he said.

The night’s main event featured a clash of veterans with outsized personalities. Danhausen, a featured visitor and veteran of larger national pro wrestling companies with television audiences, entered in monstrous face paint and gothic attire. He clashed with Anchorage-based Chris Wilde, whose musclebound physique writhed toward the ring in pink tiger-striped trunks and fishnet stockings.

Chris Wilde is a character performed by Isaac Worth. “A lot of it is just taking my own personality and just like how can I ramp this up and what can I get away with in terms of outlandishness,” Worth said. “I’m not doing it tonight, but normally I’ve got body glitter on.”

Worth, 36, who does at-home caregiving for seniors by day, said being a wrestler is a dream he’s been chasing since he was 5. He wrestled previously in Hawaii and has worked with 907 Pro Wrestling since 2021. It’s all part of giving his life to art, he said, which he said also includes some combination of acting, painting, sketching and music. He recently finished a production run on the cast of “Rocky Horror Picture Show,” he said.

“I’m greedy. I just want to do it all,” Worth said.

Worth’s Chris Wilde managed to vanquish the amusingly evil visitor, despite the hex placed on him in the throes of combat. Wilde then danced with and serenaded audience members at ringside.

One of the fans, Russ Ariel, said Worth was one of a few 907 wrestlers who have a hard-to-describe “it” factor that could lead him to opportunities beyond Alaska. Ariel is a longtime pro wrestling fan who has attended wrestling at small independent shows all over the West Coast, he said. “I feel this product is just as good as anything down there,” he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ariel predicted he’d be dragging at work the next day after a late night watching wrestling, but it would be worth it. People who disparage it are missing the point, he said. 907 events are a place to set aside inhibitions and “uncross your arms.” It can be two things at once,” he said.

“It is dumb and it’s beautiful,” he said. “Of course it’s ridiculous. Of course it’s ridiculous. But it’s so much fun.”

• • •