Face it: Our food system is broken. What we waste is astonishing. It’s a classic case of “out of sight, out of mind.” The greater tragedy is that the failures in our food system are compounded by imbalances in our economic system, and vice versa. Disadvantaged populations are the first to suffer.

We don’t have a food shortage. We have a distribution shortage. Restaurants throw out tons of food each week. So do supermarkets, hotels, retailers, businesses, hospitals, schools, and farms.

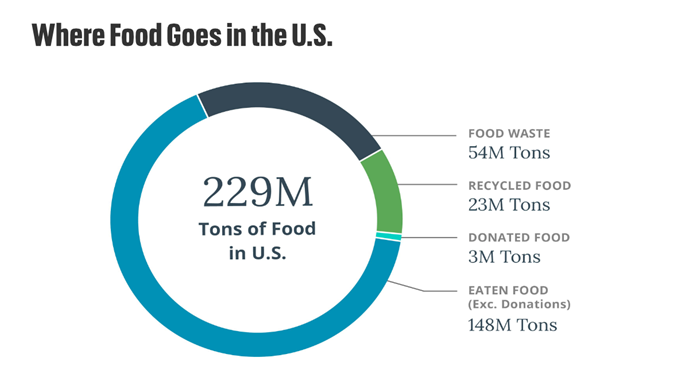

Uneaten food accounts for 38% of all food produced in the United States. Most uneaten food is either tilled under at farms, landfilled, or incinerated; only a fraction of it is donated.

At the federal level, diverting surplus to food rescue organizations became an important focus for charitable giving. Federal incentives sought to stimulate that, and they’ve been enormously effective, with food donations rising 137% nationwide at one point.

Importantly, the federal Good Samaritan Food Donation Act protects donors from liability for good-faith donations made to charitable organizations.

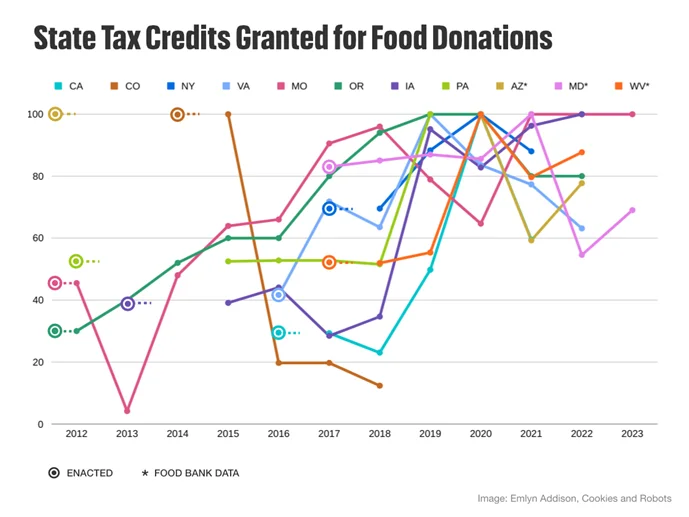

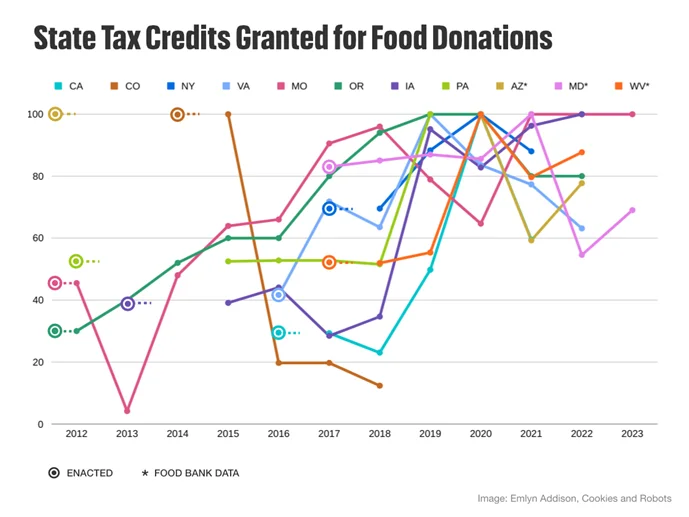

States followed suit, and while there are concerns about the nutritional value of some donated food, the overall picture of tax incentives is encouraging:

Some factors to consider for this chart:

The actual dollar figures for states represented here vary widely. Each state sets a cap on the total number of tax credit claims it will grant per fiscal year. Bigger states will have higher caps, and more populous states like California will see more donations and process more claims than a less populous one like Virginia. So, to better visualize the data for comparison, each state’s figures are presented here as percentages of their highest reported year to date.

The availability of data varies from state to state. The figures were gleaned either from states’ annual financial reports or from food banks. (Maryland and Nebraska passed legislation in 2023 so there is as yet no state data.)

Colorado, Kentucky, and the District of Columbia repealed their tax incentives for food donation. Only Colorado had data available. Some states have a sunset clause written into the law so the tax credit option will expire if the law is not renewed. However, most of these states’ laws include a provision that covers claims made before the law’s expiration.

Some tax filers don’t claim a credit for the food they donate, so actual quantities of food donated are generally more than what is reflected in states’ financial reports.

State tax credit data is inconsistent and incomplete but there’s enough to indicate an upward trend. And, in a majority of states, that upward trend appears to begin in the years following the laws’ enactment.

The tax incentives vary but all of them work by crediting a percentage of the value of the goods donated.

A representative from the Maryland Department of Agriculture was positive about their program, noting, “It’s rewarding farmers for what they were already doing.” And this may be true for other states. More comprehensive data from food banks may corroborate the effectiveness of these incentives.

In New York, Virginia, West Virginia, and Oregon, the number of claims submitted — or granted — declined during the pandemic. In Iowa, Maryland, and Missouri the reverse appears true.

Virginia’s figures bear scrutiny. After the law’s passage in 2016, claims for food donations more than doubled over the next three years. But, even before the pandemic and subsequent federal assistance programs, food donations in that state began to dip. According to the Federation of Virginia Food Banks, donations are down 30% despite rising demand. The Rhode Island Community Food Bank is facing the same shortfall.

Some states only grant claims for crop donations from farms, excluding contributions from individuals or businesses. New York, Maryland, Iowa, Oregon, Virginia, West Virginia, and Colorado fall into that category. In fact, only California, Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Nebraska offer tax credits to individuals or businesses.

In that respect, the laws may be falling far short, as residential and business sources account for two-thirds of all food waste nationally:

In Rhode Island, 61% of our food waste comes from residential sources alone. Rescuing and donating even a portion of that wasted food would make a difference for the more than 91,000 Rhode Islanders who can’t meet their basic food needs.

Currently, just one-third of the food distributed by the Rhode Island Community Food Bank is donated. Almost half of it is purchased. With the cost of food rising, it’s not difficult to see how surplus from restaurants, supermarkets, food businesses, farms, and fisheries could help food rescue organizations serve more people in need.

Of households in Rhode Island that face food shortages, close to two-thirds are Hispanic and Black. Food equity and access should be foremost in redistributing the excess from a wasteful food system.

“The community we serve here at Lincoln Housing Authority would greatly benefit from an increase in food distribution,” said Kayla Lanoie. “Rent is now going up, medication prices are increasing, the cost of food is skyrocketing. Many residents are left with the uneasy thought of ‘Can I afford to eat?’”

Yet incentives themselves are not a fix-all. Community composters are understandably wary of such legislation, no matter how well intentioned. New York City’s recent budget cuts to community programs was a gift to entrenched waste management companies who want that business. Their profit model does not prioritize place-based community programs, or sustainable systems, or reconnecting people to their food.

But we must differentiate between “uneaten food” and “food scraps”: these are two different things. Uneaten food can be donated to feed families, food scraps cannot — or they can only do so indirectly, as compost. In the case of packaged foods and others that are difficult to process into compost, donation-based solutions are often preferable.

The key driver here is: Feed the people first, feed the soil second. So rewarding food donation, as an alternative to landfilling, is the first line of defense against rampant food waste.

There’s enough evidence to support tax incentives as an effective tool for that. Extending those laws to include individuals and businesses would not only give food rescue organizations more to work with, it would also see that waste diverted from landfills or incineration. That’s a win for the environment.

And there’s an economic upside too: The costs to produce that food — water, energy, land, fuel, animal feed, and wages — are wasted the moment it’s tossed in a dumpster. Donation helps to recoup some of those costs through tax credits.

Heather C. Zoller, owner of Z pita chipz in Warren, is supportive of tax incentives: “We strongly believe that donating excess food is a no-brainer. More people need to be educated on the positive impact this has within our communities. Tax credits would help to do just that because let’s face it, saving money always incentivizes people.”

Other states have paved the way for boosting food donation. Rhode Island must create its own law to reap the benefits that tax incentives promise. And it can be crafted to coexist with our flourishing community programs.

“Now is the time to turn common sense into common practice,” said Dana Siles, who is director of partnerships for Rescuing Leftover Cuisine, and a member of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council. “Food donation is socially, environmentally, and economically practical, it is just, and it is a win-win-win.”

That work is underway, led by the Rhode Island Food Policy Council which, together with partner organizations and local businesses, has drafted a letter urging Gov. Dan McKee to introduce a tax credit for food donation in his proposed 2025 budget.

Enticing businesses to choose donation over disposal of their surplus food can have a substantial impact on Rhode Islanders facing hardship. And its restorative effects on the environment and the local economy is the cherry on top.

To make a contribution or to learn more about food donations in Rhode Island, visit the Rhode Island Community Food Bank.

Emlyn Addison is a writer, composer, and environmentalist. He writes about sustainability and climate technology at Cookies and Robots. Addison grew up in South Africa and has been a Rhode Island resident for 20 years.