Luiz Braga, “Netuno II,” 2020/Photo: Luiz Braga

Luiz Braga, “Netuno II,” 2020/Photo: Luiz BragaLuiz Braga is a visual poet. An unmistakable figure in contemporary Brazilian photography, the so-called “Amazonian photographer” is talkative, sharp-witted, generous, acidic, sensitive, humorous and keenly perceptive. Now sixty-nine and behind the lens since 1975, Braga still burns with the spark of curiosity more often found in the most eager of young apprentices. Ever hungry for knowledge, thrilled to share what he’s learned, and restless for what he hasn’t yet discovered, Braga approaches photography as a fantastical language—a poetic all its own, in which fiction and reality blur to the point of irrelevance. Not that he minds. He sees himself, after all, as a maker of “visual fables.”

In an interview with Newcity Brazil, timed to coincide with “Luiz Braga—Imaginary Archipelago,” on view at Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS), in São Paulo through September 7, Braga reflects on his artistic and intellectual formation, revisits the stylistic influences that shaped his eye—from fine arts to cinema, ponders the impact of technology on photographic language, and speaks with heartfelt reverence for the Amazonian people and territory—which he has never ceased to call home.

You studied architecture, which is interesting—not a formal education in photography, but in fine arts. How did that background shape you as an artist?

When I enrolled in architecture school, I already knew it was what resonated most deeply with my soul. It all happened in parallel—I was seventeen, almost eighteen, when I opened my first photography studio, in 1975, and started my degree in architecture. The subjects that really captivated me were those tied to the fine arts—art history, aesthetics, architectural history, drawing and composition, painting. Those were the ones that lit me up.

Even so, it was always very clear to me that I wouldn’t become an architect—but that my “architecture” would be built through images. You can see that in the way I design my exhibitions. In the current show at IMS, for example, I was involved in selecting the colors, working alongside the installation team and the curator.

But what really shaped my mind as a child and teenager were the books my father collected about the world’s great museums or the volumes from Editora Abril on the masters of painting. My artistic foundation was far more aligned with fine arts—with the work of Rembrandt, Degas, Renoir, Monet—than with photography itself.

By the time I began taking an interest in the work of photographers, the great masters, I was already making photographs myself. At that time, we Brazilians were still very culturally colonized. It was far easier for a kid like me, growing up in Belém do Pará, to encounter the work of [Robert] Doisneau, [Raymond] Depardon, [Alfred] Stieglitz, [Richard] Avedon, or [Henri Cartier] Bresson than that of [Walter] Firmo or Mário Cravo Neto, for instance.

Brazil only began to discover itself through the National Photography Week at Funarte (1982–1989), which is when Brazilian photographers started to realize there were others—other Brazilian photographers—looking at Brazil through their lenses.

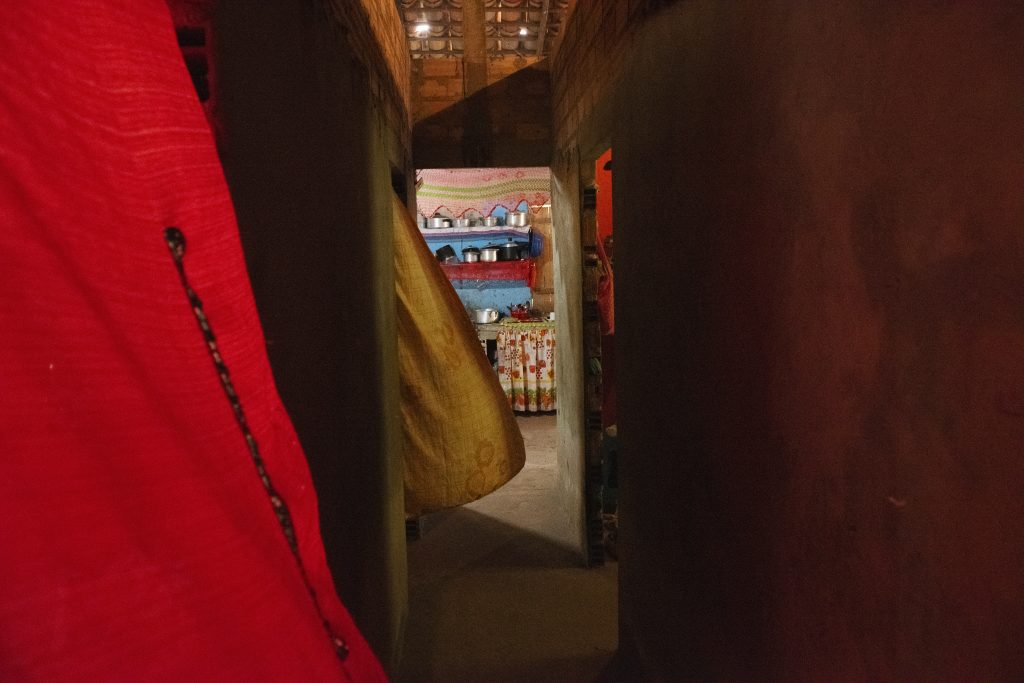

Luiz Braga, “Esperando o barco,” 1986/Photo: Luiz Braga

Luiz Braga, “Esperando o barco,” 1986/Photo: Luiz BragaSpeaking of fine arts—and after seeing your exhibition—it feels impossible not to draw certain parallels between your photographs and the canons of Brazilian art, whether it was the early Republic (post-1889) or the modernist period. Even your titles echo works like “Caipira Picando Fumo” (1893) or “Amolação Interrompida” (1894) by Almeida Júnior (1850-1899), or your own “Blue Boatman in Manaus” (1992), which calls to mind “Mestizo Man” (1934) by Cândido Portinari (1903–1962). How have these masters of painting—especially the Brazilian ones—influenced your photographic language?

In the case of those Brazilian painters, it’s more a matter of affinity. I only really came into contact with their work once I was already developing my own. Some people make that comparison to Portinari, perhaps because of who and what I choose to focus on—even more than how I look. In my case, it’s the caboclos, it’s Black communities, it’s the Indigenous ancestry of the North.

There’s also that layer of popular culture—the street festivals, the religious processions, the faith. It’s more a matter of shared ground than something I can trace directly to Portinari as a starting point for my language, because that’s just not how it happened. And I wouldn’t mind saying so if it were! But I’m not a tributary of those painters.

One photographer I was thrilled to discover was Mário Cravo Neto (1947–2009). I realized he was an outsider—he didn’t live in Rio or São Paulo; he stayed in Bahia, even though he traveled all over the world. His work was deeply rooted in Bahia and its culture. That gave me a kind of reference, the courage to say: it’s possible. I don’t have to move to São Paulo or Rio to do something powerful, something that might reach beyond the borders of my city.

Back then, it was common to hear that old saying: “He caught an Ita boat from the North and moved to Rio” [a reference to the ship Itapé, made famous in a song by songwriter Dorival Caymmi]. People would ascend to a certain social level and say, “You have to leave Belém if you want to be somebody.” I never did that. My work traveled far more than I ever did. I went out to seek knowledge, but I always came back.

Brazil doesn’t know itself—that’s the truth. Especially the Brazil that’s farther out. And Belém is far away.

Since the days of colonial Brazil, there’s been a deeply ingrained notion in our culture of “province” and “metropolis”—an extension of the old idea of “kingdom” and “colony.” In that sense, the north of Brazil has long been viewed primarily as a site for exploitation—first by Europeans, and later, even by the country itself, through the Rubber Boom (late nineteenth to early twentieth century), or illegal gold mining, for instance. Your choice to remain in the north and to create from within it seems, then, like an ideological act of decolonizing the way that region is perceived…

Absolutely.

Luiz Braga, “Caixotes do Zé,” 1986/Photo: Luiz Braga

Luiz Braga, “Caixotes do Zé,” 1986/Photo: Luiz BragaHow does that ideology manifest in your work?

That was an intuitive stance. I had no idea how deeply rooted my ancestry was within me. It took time to mature that understanding and see it clearly. But I always sensed, from a very young age, that we [people from the North] were different.

I remember feeling, in some way, angry when I would go spend summer vacation at my aunt’s place—she had moved to Rio de Janeiro. I’ll never forget how my cousin, who was also from Pará, and his friends from Rio used to refer to me: “Here comes the Paraíba!” [a derogatory slang used to mock Northeasterners and Northerners]. It was as if I were somehow lesser, a second-rate person. That always hurt me deeply, because I knew it was unfair.

It’s hard for people to understand that you can make something of yourself without having lived abroad, without having studied abroad. That’s something Brazilians really struggle with: this constant need to be under someone else’s rule—culturally, too. As if we were incapable of producing knowledge that didn’t require external validation.

In these fifty years, I’ve witnessed such wisdom, such inventive thinking, so many solutions… It’s a whole encyclopedia! But it’s an oral encyclopedia. It doesn’t have the financial power of, say, an American or French university that attracts talent from all over the world. Still, the lack of diffusion and recognition doesn’t make that knowledge any less meaningful—it’s worthy, it matters. Every place has its own intelligence, its own way of understanding, its own myths.

Take this exhibition, for example. There’s a section I called “Map of Eden,” which I built gradually, reflecting along the way. Later, I realized it actually pointed to an Indigenous myth about a “Land without Seas,” which corresponds, in our Western culture, to the idea of Heaven.

Another example: “Night.” The origin of this work came from a tool—night vision. There’s a story about the Night that my father used to tell me as we rocked in a hammock. He said that, according to Indigenous lore, Night had once been trapped inside a tucumã seed. A curious Indigenous boy cracked it open, and only then did Night come into being—it hadn’t existed before. If that story had come out of Greece, the entire world would know it.

Back in the 1980s, the only artist in this region looking inward like that was Emmanuel Nassar [Capanema, Pará, 1949]. No one else. The others were all aligned with classical aesthetics, with middlebrow taste. The outskirts [of the city] I photographed only appeared in the news when someone died or when a crime occurred. But were people with agency—central to the work, not just depicted? Never. That’s something I’m proud to say I embraced.

There’s this whole discussion in the book “Where We Stand.” I didn’t live there [in the outskirts], that’s true. But so what? I had a real connection, a deep affection for that entire region—one I returned to hundreds of times. I saw children grow up, businesses evolve, the river docks vanish. I witnessed that history and built a body of work around it.

Photography still carries that legacy of the photographer as exploiter/colonizer. There’s this distant gaze directed at Africans, South Americans, Afro-descendants—a gaze that looks down, that dominates, very much like European photography. It often comes from someone who didn’t live there, didn’t truly connect, who simply spent a brief period and shot beautifully crafted images—but they’re almost like visual property deeds. Once I understood that, I knew I didn’t want to reproduce it.

Of course, this [ideological stance] is something that was built over time. When I was seventeen or eighteen, I didn’t have the maturity to grasp any of this. But with time, through all my travels and especially through listening—listening to those communities and people—I came to understand how rare and profound their wisdom is. And yes, with gentleness, without waving a flag about it, that value is present in my work. It’s an affirmation of that heritage, of the colors born from that ancestry.

Luiz Braga, “A Preferida,” 1985/Photo: Luiz Braga

Luiz Braga, “A Preferida,” 1985/Photo: Luiz BragaNow, let’s speak about photography as a language. There’s often an expectation that a photographer, camera in hand, would somehow “capture reality.” However, the very title of your exhibition at IMS, “Imaginary Archipelago,” reveals a contradiction to that idea. On the one hand, there’s the recording of factual reality, but on the other hand, you bring your own poetic vision into this factual record. How do these two sides coexist in your work?

I started photographing at a time when this idea of photography as a document—to show that something exists, that reality exists—was very clear. Photography in 1975, at least the kind that reached me, was like that. The kind made by documentarians like Zé [José] Medeiros (1921–1990) or the great photojournalists from Life magazine, who were there to tell stories, to create photographic essays, and so on. I can’t deny that, in the beginning, my photography definitely leaned in that direction.

As I matured, photography allowed me to return, to revisit [what I had captured]. This exhibition, in fact, is only possible because I kept everything I ever made and always revisited my work. And it’s amazing: every time I revisit it, new pathways open up—pathways that, at the moment of the famous shutter click, weren’t clear to me at all. I needed years to mature enough to realize that there were absolutely fable-like layers—subjective, fictional layers—that we didn’t really talk about back then.

Maybe this exhibition is the greatest revelation of what photography is to me: a great moment of fabulation. Of telling and creating stories. “The Map of Eden” room is just a small fragment, where I recreated a world—this so-called “Land Without Seas”—by subverting technique, using infrared. Anyone could ask: “Is that real or not?”

Photography will always pay tribute to reality. For example, on Instagram—you see where it was, who it was, when it happened. That doesn’t interest me anymore. It would interest me if I were there to document a civil status, or the existence of a person with a tag, like in a police file. That’s not what I’m doing, even when it might look like I am.

There’s a pair of photographs in this exhibition, one above the other—on top, some girls holding hands; underneath, the feet of some children. People often think they were taken in the same place, at the same time—but they weren’t. Placing them together like that is about creating a planet where it no longer matters where or when it was taken, but rather the existence of that world as a photograph. The time of the photograph is not the time we live in. Time is elsewhere; the place is the photograph.

When people ask me, “Where is this?,” what I feel like answering is, “It’s inside a Luiz Braga photograph.” It’s a circular existence, not a linear timeline. People still tend to see photography as something to be filed along, like in a social media feed. That has its uses in some cases. But in my work—especially the way it’s grouped in this exhibition, through panels, associations and clusters—I try to build visual fables.

Luiz Braga, “Fátima Cabeleireira,” 1991/Photo: Luiz Braga

Luiz Braga, “Fátima Cabeleireira,” 1991/Photo: Luiz BragaWhen we think about fabulation in writing, for example, the distinction between fiction and reality can be more apparent. You can fictionalize a scene, create a believable dialogue, invent an ending that serves a particular story. This is clear even in the way audiences are used to engaging with that kind of language. But in photography, fabulation happens through different kinds of subtleties, in different ways. What are these subtleties that are particular to the photographic language?

When you post a photo on Instagram, for example, and someone comes along and says, “Man, your picture brought back the scent of my grandmother’s house!”—that photo has become a bridge. It’s not even just a fable anymore. It managed to throw that person back in time and make them feel a smell in something that I know has no smell. But does it really have none? It does! So, the photo becomes a portal.

The possibilities are endless. That’s why I think photography can’t be confined just because it is made from capturing reality. Take painting, for instance: if I were a painter, I wouldn’t even have to explain this. I would just pick up the brush and paint.

[Over the years] I’ve experimented with thermal cameras; this “Map of Eden” series came from my restlessness about a camera that I dug into until I found a way to use it differently from what it was meant for; even the color material, those blends of light, came out of a mistake—using the wrong film in the wrong context—and it worked.

That’s something I always try to play with. In a way, it’s a fictional tool, because the moment I start subverting technique, I’m already saying that I can “write” this story, but I can also swap the letters—and it will still be interesting for whoever is willing to read it.

You touched on an interesting topic: the relationship between certain technological developments and photography. You began using digital cameras in the mid-2000s, and one technology you’ve adopted since then is the “nightshot” mode. What exactly is this technology, and how has it impacted your style?

In the early 2000s, it was getting hard to buy film, to develop it, to make prints. Labs were shutting down. Digital photography emerged, and I decided I wanted to buy a camera to see what it was about. I bought a Sony in São Paulo, eight megapixels—today we’re talking about one hundred!—with a wonderful, luminous Zeiss German lens. I started shooting the same color work I was doing before, but with it.

When I saw the results on the computer, I was shocked. It looked fake. There was no tonal gradation, no texture, no grain, no relief. It looked like a computer-generated image—hyper-real, hyper-sharp, boring. I thought, “Holy shit, I just threw my money away!” So, I went back to the manual.

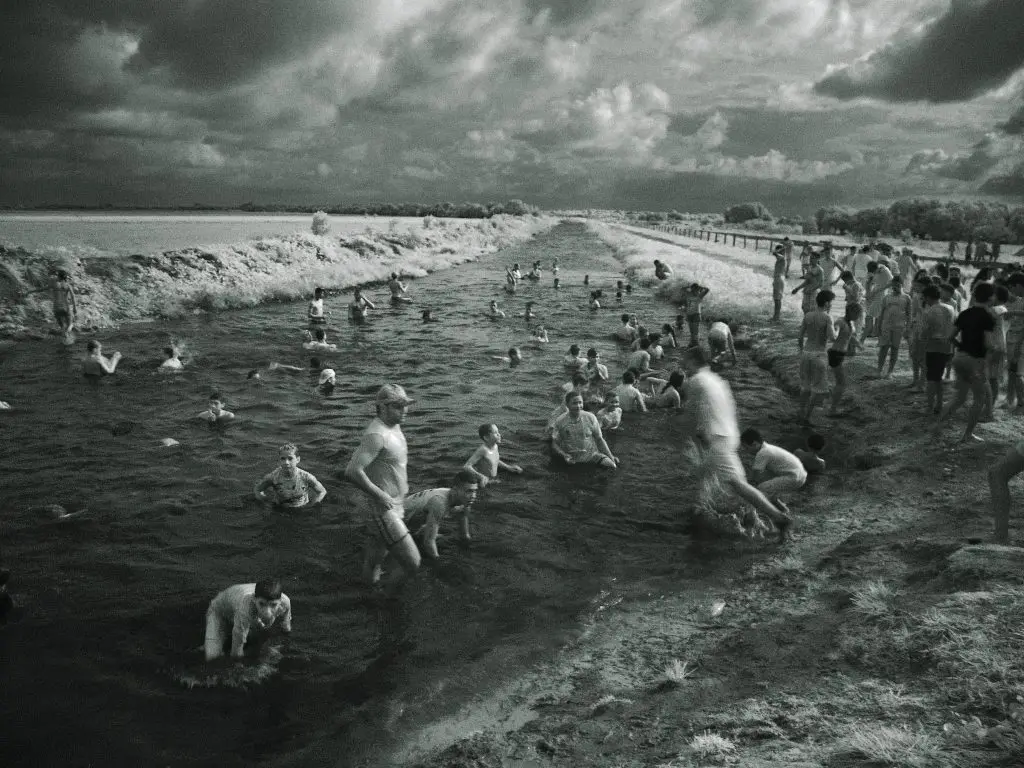

Luiz Braga, “Banho Marajoara,” 2013/Photo: Luiz Braga

Luiz Braga, “Banho Marajoara,” 2013/Photo: Luiz BragaI spent a lot of money and time experimenting, reading, trying things that didn’t work. People think artists are these guys who just show up, paint, and that’s it. Hell no! You need a lot of dedication, you have to be committed. I don’t believe in results without dedication. You have to allow yourself to experiment, to fail.

That’s when I found out this camera had a “nightshot” feature—a Sony patent that allowed you to capture images in total darkness without using flash. I thought, “I’ll give this a try.” I programmed it into a button, and when I started shooting, already out on the outskirts of the city, I saw that the result was incredible—grainy, greenish, gritty. I thought, “There’s a path here.”

I started photographing at night, but then came this nagging feeling: “What if I use this thing during the day, what would happen?” At first, it didn’t work—of course, using something made for the night under our harsh equatorial sun… I tried all kinds of filters: red, green, polarizer, neutral density—and nothing. Digging deeper, I found a factory in [South] Korea that made surveillance filters—you know, for monitoring borders, prison yards, real police stuff. I bought two of those filters. It took three months for them to arrive—you have to be patient.

I used them to shoot that photo of the man pushing the boat that says “Fé em Deus” (Faith in God). When the photo showed up on the monitor, I thought, “I got it!”

Why was I so happy? First, because I had been chasing that result for almost a year. And second, because I realized in that very first photo that, through this subversive tool, I had finally managed to bring the forest into my work. Up until then, the forest, the vegetation, the trees, the water sources—they weren’t part of my work. That was deliberate. I didn’t want to reinforce the stereotype propagated by National Geographic and others, this idea of my land being just a “green stain” filled with jaguars, Indigenous peoples and devastation. I know all that exists, but my work shows there’s so much more beyond that.

When I managed to recreate a world, this “Land Without Seas” using this technique, I kept working with it and named it “Nightvision”—actually, it was [curator and art critic] Paulo Herkenhoff who came up with that name.

After thirteen years, the camera died of old age. I bought another used one, and it also died shortly after. But I thought, “I want to keep doing this because this planet I created interests me.” So, I took another camera I had and sent it to a lab in the United States to have it dismantled and converted to capture only infrared.

That’s the camera I’m working with today. It has this magic—this slightly surreal look that gives the images a kind of enchantment. It’s perfect for photographing the forest, the river, even the human body. Anyway, it’s a path that’s still evolving.

At the IMS, there’s the largest exhibition I’ve ever done within this series, which continues alongside my color work. Sometimes I also convert images to black-and-white… I try to explore all the technical possibilities that these fifty years have given me, without letting myself get trapped in mannerisms.

And look: just for space reasons, we didn’t have a room in this show where there would be no images—only my voice speaking about what the images I didn’t take would have been, could have been, or might still be.

Luiz Braga, “Barqueiro azul em Manaus,” 1992/Photo: Luiz Braga

Luiz Braga, “Barqueiro azul em Manaus,” 1992/Photo: Luiz BragaSounds like a great idea for a future exhibition.

I think so too, because it would leave the viewer with the task and the mission of building their own world, based on their life experience and references, from my provocation.

I remember that way back, at my first exhibitions, people would often ask me, “Is photography art?” I had to answer that dozens of times.

If you pay close attention, back in the days of that fotoclubista [of informal photography collectives] movement—the one of Geraldo de Barros, [Thomaz] Farkas—there were some technical and aesthetic tricks that subverted photography, but aimed to make it look more like painting. It was as if photography, stripped of those embellishments, couldn’t be seen as art. Solarization, posterization, photomontages… all of that was created so photography could have a sort of “artistic” veneer.

But photography is art, with or without the extra frills. Just like I don’t believe that photography is art because of the format. People have even said to me, “This photograph is so small, and yet it costs so much!” And I say, “Man, I’m not selling fabric by the square meter!” There’s still a lot we have to deconstruct.

Going back to the issue of technology: today, smartphones come equipped with increasingly sophisticated cameras at prices that, while not exactly popular, are accessible to a large portion of the population. In your opinion, what impact has this exponential growth in the number of people with access to high-quality cameras had on photography as an artistic language?

I’ve always liked good equipment—high-quality lenses, cameras, film, good labs. I’ve never been lenient about that, because this is what I chose to do with my life, and I want to do it well.

I have a smartphone, and I sometimes use it in daily life, but I rarely trivialize it the way I see others do. I generally like to take photographs with the intention of looking at them and having them be looked at. When you take pictures in such an urgent, impulsive, hasty way, I think it doesn’t allow for what I understand as photography—a form of expression, of communication, even of fabulation.

Today, practically every outstretched hand is holding a phone—either to take a picture or to hand it over to a thief. It’s staggering how many images are circulating. Often, they lean toward a kind of exaggerated and foolish narcissism. It’s like the world is in a frenzy to photograph itself. It’s pure egocentrism.

And in that case, it doesn’t matter if you’ve got a top-of-the-line camera with features most people don’t even know how to use, because they don’t care. What matters is whether it takes a good selfie, whether there’s a filter to smooth their skin, to make them look like a Korean drama actor. To me, that cheapens the device—but I don’t consider what these people do to be photography.

They could be making photography—and that would be wonderful. Because when they do so, they become sources for me. I look and think: “Wow, what an interesting take on that place! What a compelling person! Great framing!” That does happen. But most of the time, it’s selfie after selfie after selfie. It creates something I call “photorrhage,” a “photographic hemorrhage.” And like any hemorrhage, it’s never beneficial.

Your take seems to reveal a need for a certain aesthetic sensibility in order to make what you consider “photography.”

It requires time, reflection, affection. You can’t be doing it all the time, constantly. That’s not healthy. It’s no use having a great device if you’re not making reasonable, thoughtful use of it. Choosing is at the core of photography. Choosing, from within a 360-degree field of vision, what I find meaningful. And how I’m going to convey that. But it’s nothing like that—it’s just click, click, click. People seem like crazed grasshoppers. That doesn’t work.

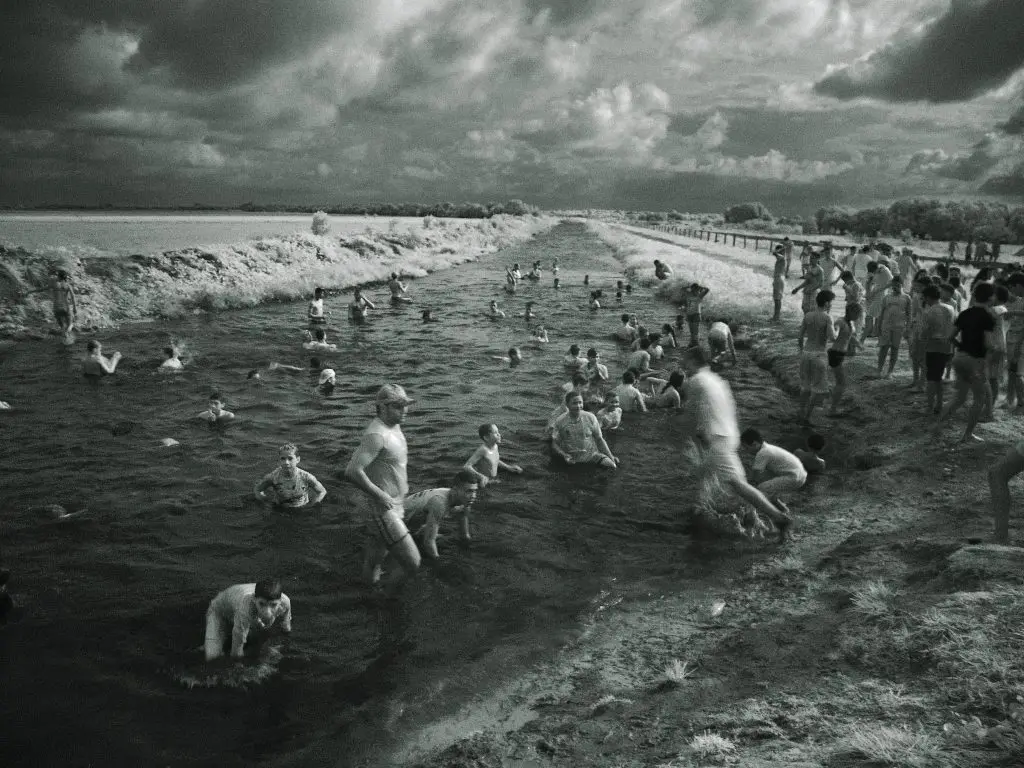

Luiz Braga, “Casa de farinha,” 2019/Photo: Luiz Braga

Luiz Braga, “Casa de farinha,” 2019/Photo: Luiz BragaSpeaking of that aesthetic sensibility you associate with photography, there’s something deeply cinematic about your work. Sometimes it’s wide shots, sometimes close-ups—faces, details, interiors, exteriors… It’s as if you were composing different narratives.

Cinema has definitely been a major influence in my development. My father loved cinema and used to take me often, and as a teenager, I went all the time. Interestingly, in Belém do Pará during my teenage years, we might’ve had access to more films by cinema’s great masters than many cities around the world. There were a few alternative screenings—non-commercial ones—where we’d watch, on film, because there was no video yet, directors like Stanley Kubrick, Fellini, Antonioni, Buñuel, Wim Wenders….

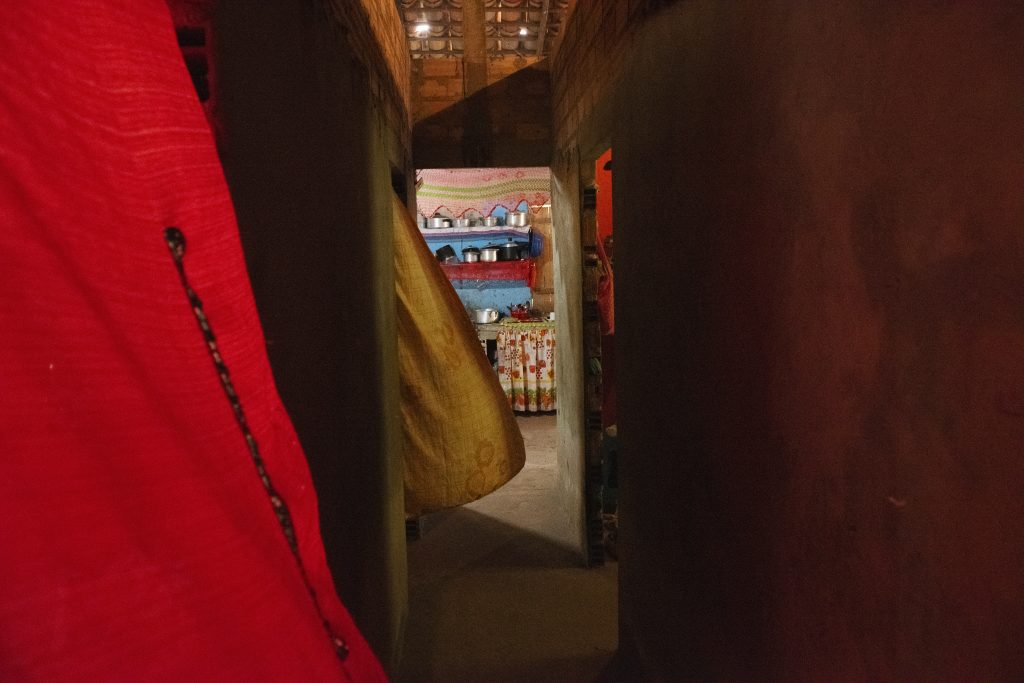

As we walk through the exhibition, there’s this almost cinematic record of a kind of aesthetic sensibility often labeled as “camp”—or maybe “kitsch”: the extravagant fashion, home and shop décor filled with media personalities, logos, Catholic saints, contrasting colors… And at the same time, all of this coexists with traditional elements of the region, like fishing tools and boats, buffalo riding, the architecture of the houses, even pre-Columbian Marajoara ceramics. What’s your take on the coexistence of this so-called “camp/kitsch” aesthetic from Northern Brazil with that atmosphere of ancestry, Indigenous cultures, and forest that we were just discussing?

When it comes to this aesthetic, around here we call it estética caboca, or caboquice. It’s the way these riverside communities—born of the mix of Afro-descendants, Indigenous peoples and Portuguese—express themselves. They’re very colorful, very exuberant.

There’s a section of the exhibition with four images, all from the home of one person: Dona Socorro. Dona Socorro is a muralist. With limited access to certain materials, she solves it with fabric. They line the walls with fabric, don’t use doors—just fabric to close things off. If you want to go into a room, you pull back a curtain—there’s that photo of the girl sitting on a bed seen through a slit in the curtain.

When I started focusing on this aesthetic, a lot of people turned up their noses, calling it tacky, “kitsch.” But I’ve always seen it as a legitimate expression of a way of being in the region. To me, that’s what sets us apart from the rest of the world. A world where cars all look the same, clothes are increasingly uniform, and music—sometimes you don’t even know where it’s from anymore. What I see in that universe, which shows up in my work, is a way of being that’s a distinctive trait we can be recognized for. Even the way people sit, their gestures—it’s something very specific to us. It shows in our music, in our lights.

I go to Marajó [archipelago] a lot. I’ve focused much of my work there because of the warm welcome and because that aesthetic still survives there very strongly. Many places that appear in the show—super colorful, with paintings of the forest on the walls and popular art—are now beige. That off-white, bland tone. We’re not in a Maison Hermès; we’re in the Amazon. It’s a whole different thing, a whole different place. Every place has its own color. We have our color. And I don’t see why we should give it up just to look good in someone else’s photo.

Luiz Braga, “Interior casa Gerlane, Movimento II,” 2024/Photo: Luiz Braga

Luiz Braga, “Interior casa Gerlane, Movimento II,” 2024/Photo: Luiz BragaLastly, I can’t avoid asking a more political, institutional question. You began photographing in the 1970s, at the height of the civic-military dictatorship (1964-1985), and have lived through several governments, from the return to democracy to today’s leadership. What has changed since then, and how have those changes impacted you as an artist?

I supported my artistic work through my studio income—doing product photos, backshots, board reports, political campaigns, debutante parties, institutional portraits, architectural photography, aerial shots… That money allowed me to do the work you see in this exhibition. I didn’t receive any grants or sponsorship to do this.

My 1980 exhibition, held during the dictatorship, featured giant full-frontal nudes in a space that was subversive itself, because it was a nightclub, not an art gallery. People came to see it and even brought their children, strollers and all. I didn’t have any problems. If I wanted to romanticize it, I could—no one could prove me wrong. But I won’t, because that’s not what happened.

My father, who was the director of a psychiatric hospital, sheltered some students who were being persecuted. He hid them in the hospital’s attic because he truly didn’t believe students should be persecuted for protesting against something absurd. My uncle, who was an admiral in the Navy in Rio de Janeiro, was arrested by the military and stripped of his position. He was removed from office for not supporting the coup—and then he studied literature and carried on with his life.

I navigated through all of that. For example, during [President Luiz Inácio] Lula [da Silva]’s first term (2003-2006), when Bolsa Família [a social welfare program] was created—and even under [former President] Dilma [Rousseff] (2011-2016)—I noticed that in the communities I visit, people experienced a modest improvement in their quality of life. Homes that were once made of wattle and daub became brick houses. People gained something.

But, to tell you the truth, I live in a region that lives on the “lesser” side of inequality. The Amazon is still largely unknown—it’s the backyard. [Writer] João Moreira Salles put it well in a conversation we had, and in his book. This place is the outskirts.

That’s why this COP [UN Climate Change Conference, to be hosted in Belém in 2025] is so important—to say: “We’re here, we exist!” And it has to be held here. If you’re going to talk about the climate and the Amazon, you can’t do that in São Paulo. It has to be right here. I hope it brings some kind of visibility to this region.

I’m really happy with the visibility the IMS is giving to my work. I’ve been talking about everything we’re discussing here for the past fifty years, but it never had this kind of reach. I can see it in the media response—people getting emotional. Someone said, “This exhibition is both a photography lesson and a lesson in Brazil”—and that second part really moved me. Because that’s what it’s about.

But it’s not propaganda. I don’t believe in pamphlets, because pamphlets get tossed out and end up wrapping fish. If you can plant an idea in someone’s mind, that’s way more effective. And photography makes it possible.

“Luiz Braga: Arquipélago imaginário” (Imaginary Archipelago) is on view at Instituto Moreira Salles, Avenida Paulista, 2424, São Paulo, through September 7.

Olavo Barros is an arts-oriented journalist, independent curator and master’s student in art criticism at the Universidad Nacional de las Artes in Buenos Aires. With twelve years of experience in writing, planning and implementing projects for companies and agencies, he has also contributed to the creative and communication teams at São Paulo Art Museum (MASP) and ArPa Art Fair. As a scholar, he researches the intersections of modernity and contemporaneity in Latin American cinema, literature and visual arts.