Hiker-stink comes from hard work, polyester, and nutrition. That oh so familiar urine smell is ammonia buildup caused by an under-fueled body breaking down muscle protein to power itself. Even wool cannot overcome poor on-trail nutrition.

We have a fear of ramen-bomb thru hikes. Visions of a continuous noodle trail stretching from Maine to Georgia and Mexico to Canada dance in our heads.

To keep us fueled to run like finely tuned (vintage) Formula 1 cars, I did a deep dive into the nutritional science literature. I enlisted the help of our Health Coach and two registered dieticians. Here I tried to summarize months of research and planning. I you are not hungry for nutritional data, wait for the next blog, it is all about eating, not planning.

Please know I don’t claim to be an expert. I do feel good about our nutritional plan, even while recognizing it be subject to the wobbles of reality, not to mention hiker hunger and town food.

Nutrition 101: How Many Calories Do I Need for Backpacking?

A good starting place for general nutrition is the Dietary Reference Intakes calculator.(1) Backpacking is a unique activity so general references need adjustments. Most of the science is based on the Pandolf equation.(2) Outside Magazine has a very good article, The Ultimate Backpacking Calorie Estimator(3), that provides a detailed calculator.

Establishing Base Rate Calories for Optimal Nutrition

The adult human basal metabolism rate (BMR) runs roughly 1200 to 1800 calories a day. That is what a body spends on its internal workings.(4) Nutritionally, the more active you are, the more calories you need. All things being equal, it appears that some bodies use more calories than others for the same amount of work. This is called the “thrifty gene hypothesis.”(5) Hiking with a pack adds 200 to 500 calories an hour, depending on your thrift level, weight, gender, pack weight, and the terrain. Broadly speaking, hiking 8 hours a day adds 1,600 to 4,000 calories per day to your BMR.

During a visit to a nutritionist, I had my body basal metabolism measured. My BMR is 1500 calories a day. That figure aligned closely with two mainstream fitness watches I use. I was encouraged that the watches might provide good estimates for users.

Thrifty Genes

We have three years of smartwatch data tracking our food, hydration, and exercise per day. I know that our baseline calories are 1500-2000 calories for mundane exercise of 2-3 miles of moderate mountain hiking without packs. With a pack, we typically use 2500 to 3500 calories per day for a 6-8 mile mountain hike of 1000-2000 feet of elevation change. I decided to target 2500 to 3000 calories per day for a typical AT day. This might be low but seems a good starting point.

Establishing Nutrition Macros

Total calories are a major part, but not the whole nutrition story. Thru hikers often rely on the tried-and-true diet of fat and easy to digest carbohydrates to reach their caloric goals. They are cheap, available, and easy to prepare. Unfortunately, this type of diet does not fuel the body optimally and is likely one of the underlying issues with hiker stink and hiker hunger.

Social media would have us believe carbohydrates and fat are bad and protein is good. A diet of crisps and French fries may be protein deficit but if you also eat that hamburger and taco, protein deficits are unlikely. This scheme may work well for thru hikers on town days, but not all days.

A good ratio of fat, carbohydrate, and protein is nutritional key to optimal performance. One of the tricky parts of finding the right ratio is that there are ranges that vary for individuals based on age, activity, and health status.(6)

- Protein: 10–35% for people older than age 18 years

- Fats: 20–35% for people ages 4 years and older

- Carbohydrates: 45–65% for everyone

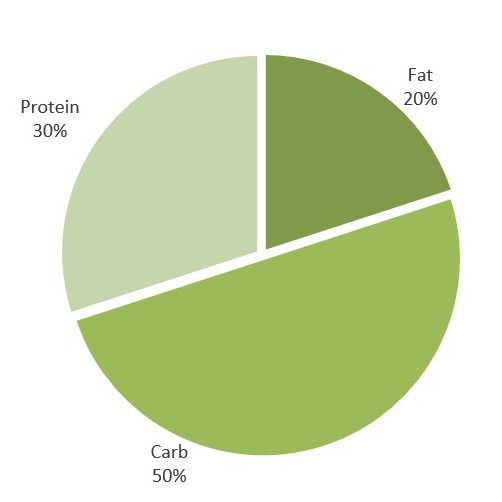

Our nutritional goal was to get enough fat, carbohydrates, and protein that our bodies don’t have to go shopping our muscles to fuel the journey. We established our ratios to be 20% Fat, 30% Protein, and 50% Carbohydrate.

Photo Caption: Average daily nutrition macros based on our dehydrated food and planned snacks

Nutrition Macro: Fats

We typically eat 20% to 30% of our calories in fats. I try to concentrate on “healthy fats” that are unsaturated fats. The Historian has a family history of high cholesterol, so I am particular about limiting saturated fats like those found in meat, dairy, and tropical oil products. We enjoy those things, but in moderation.

In dehydrated foods, fat increases the risks of spoilage, so we plan to add healthy fats like extra virgin olive oil when we prepare meals. Nuts are also a major fat source. Nutritionally, we expect to increase healthy fats to increase calories if we start to lose too much weight.

Nutrition Macro: Protein

General recommendations for protein are .66 to .83 grams per kilogram of body weight. For most people, that is in the range of 60 to 108 grams protein per day from plant or animal sources.(6) Those trying to increase (or not lose) muscle mass, may need increased protein. This includes athletes and older adults in general and older athletes in particular. Some recommend as much as 1.2 to 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight.(7) It can be tricky to balance since too much total protein, or too much protein at once, is hard on the kidneys for people at any age.(8)

Using a protein calculator set to “extra active,” I targeted us with a daily low of 80 g protein and a high of 180 grams protein.(9) While we may need more calories for very hard days, I don’t want to go much more than 180g per day protein to protect our kidneys. This suggests three meals of 20-70 grams per meal accompanied with protein in our snacks. If we need to increase calories, we will look to increasing fat and carbohydrates first.

Nutrition Macro: Carbohydrates

I feel sorry for the poor beleaguered carbohydrate. A couple of decades ago, someone branded carbs as bad when what they meant was refined carbohydrates with loads of sugar and fat added were concerning.

The noble celery stick is 60% carbohydrate. “I cut the carbs from my diet,” literally means only eating fat and protein. The body won’t run that way. Some people do seem to do better with a lower proportion of carbohydrates than others, but to discard carbohydrates is boring and not healthy.

Are Carbs Good or Bad?

Nutrition science divides carbs into simple and complex. Rather than thinking of carbs as good or bad, I prefer to think of them as fast (simple) or slow (complex). Fast carbs, those that are classified as simple carbohydrates, have rapid bioavailability. That means the body can break them down quickly. Slow, or complex carbohydrates, break down more slowly and provide more sustained energy. If you are bonking, a fast (simple) carb can pick you up quickly. A slow carb can help sustain you.

Generally, there is a role for both types of carbs, but when the simple carbohydrates are processed extensively, the same amount of food feels smaller. One research study offered participants the same meals, two weeks of ultraprocessed and two weeks of the same recipes cooked from whole foods. The participants ate more food with the ultraprocessed versions of the same foods.(10)

Cat Hole Management: The All Important Carb Component, Fiber

Ultraprocessed foods are great for hiking because they are shelf stable, easily available, cheap, and often lightweight. Unfortunately, they are low in fiber. Although hikers many do not think much about fiber it helps regulate blood sugar to reduce the incidences of bonking out. Fiber can also help stabilize the “cat hole” regimen as it improves digestion and predictability of pooping. In the longer-term, fiber can help reduce the risk of colon cancer and support a healthy gut microbiome that is crucial to your overall physical and mental health.

Our Nutritional Goal for Carbohydrates & Fiber

Because fiber is found in plant-based foods such as whole grains, beans, fruits and vegetables, it can be hard to haul in a backpack, regardless of its value to nutrition. We spent a lot of time dehydrating vegetables, fruits, beans, and grains. Vegetables and fruits have a poor calorie-to-weight ratio, but they improve nutrition and the palatability of our food. We discovered quinoa is magical. It cooks easily, dehydrates quickly, and weighs next to nothing. In addition to its fiber content, it has a good protein content.

Nutrition to Fuel the Whole Day

In summarizing our nutrition plan, I aim to provide a steady supply of fat, protein, slow carbs and fiber so our bodies are evenly fueled throughout the day.

Photo Caption: Graph of nutrition in grams per macro at time consumed and percent of daily total calories

We have a wide variety of foods to counteract boredom. If we are calorie deficient, we have extra grain packets to add to meals. We have tasty, light weight, calorie rich “add-ons” like powdered cream cheese and powdered butter. There is also some treat foods like chocolate-nut bars. Our no-sugar, chocolate whey protein drink should be a sneaky way to get us to consume more fluids and tuck in some protein after hard muscle use. Some days it will be the 4 pm “we still have a few miles to go” pick-me-up and other days it will be a reward for having made it to camp by 4 pm.

We have no way to know how our planning will work in practice until we implement it. I know it is nutritionally sound. It is lighter weight than many other options. I hope we will stink less. Only time will tell if it is palate pleasing on the trail. If it is not, we have enough food dehydrated to survive the Zombie Apocalypse.

References