The city is gearing up to add more curbside electric car chargers across the five boroughs over a decade, raising concerns among advocates that the power infrastructure will cede too much public space to motor vehicles.

The Mayor’s Office of Contract Services announced on Wednesday in the City Record that the it will soon seek a contractor to install chargers throughout the city from 2025 through the end of 2034.

The new infrastructure aims to cut carbon emissions from private vehicles — a substantial chunk of the city’s air pollution — but the chargers also take up already scarce sidewalk space and commit the curb, perhaps forever, to private vehicles. If so, it would repeat the revolutionary streetscape change the city made in the 1950s when it allowed private car owners to store their vehicles on roadways overnight.

And it comes just as the city has started planning for better uses of the curb.

“We’d be locking these curbs into serving as car storage when they might be put to much higher use,” said Sara Lind, co-executive director at Open Plans (which shares a parent company with Streetsblog). “Drivers gobble up so much public space — and make streets more congested and more dangerous while they’re at it. It’s really shortsighted to permanently allocate curb and sidewalk space in this way.

“We would never put a gas pump on the sidewalk, so why make this concession for EVs?” Lind asked rhetorically.

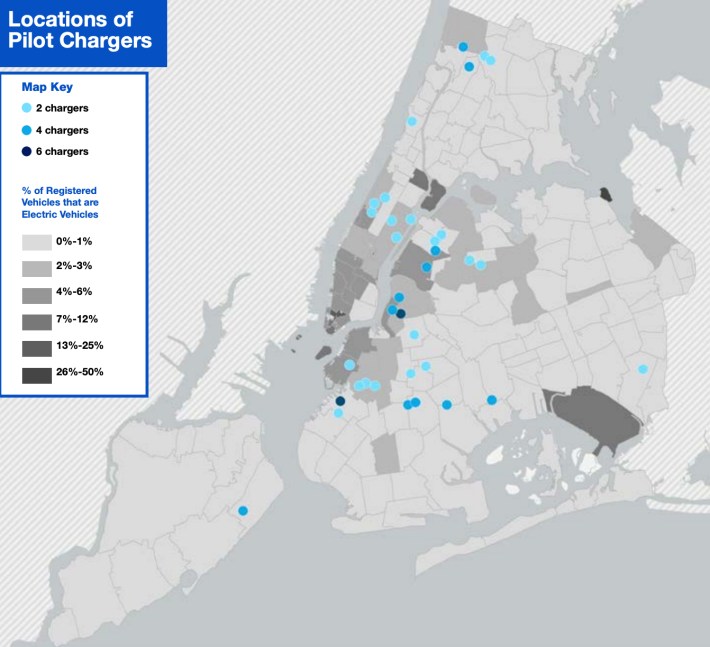

The Department of Transportation began testing 50 of the so-called Level 2 chargers with two ports each at 35 locations in 2021, charging drivers between $1 and $2.50 an hour depending on the time of day, with the parking space reserved for cars that are actively charging. City leaders have said they want to expand the network to 40,000 chargers, including 10,000 at the curb, by 2030 to reduce pollution from gas guzzlers.

The four-year demonstration project was funded by utility Con Edison. The charging company FLO installed the hardware.

At most of the sites, EVs occupied the space for about 40 percent of the time, while gas-guzzling cars illegally hogged the space for 20 percent of the time, according to a DOT report on the first 18 months of the program.

For the next decade-spanning phase, a city contractor would “implement an expanded citywide network of public [Level 2] curbside chargers,” and maintain both new and existing pilot sites, according to the City Record.

That threatens to cement more space for cars to park along the curb — as long as they’re charging — precluding other uses like curbside containerized garbage collection, outdoor dining, or street redesigns like protected bike lanes and sidewalk extensions, warned a pedestrian advocate.

“You’re going to have to go and rip out the infrastructure” to redesign the streets once chargers are in place, said Christine Berthet, the founder of the group CHEKPEDS. “It’s going to make it more difficult to repurpose the curb. It’s solidifying the free residential parking on the street.”

The city’s current standard design for curbside protected bike lane — using a row of parked cars to protect cyclists from traffic — would struggle to accommodate EV chargers, whose plugs extend from the sidewalk hardware to the car.

Berthet urged officials put chargers in gas station-like locations rather than on the sidewalk, and roll out Level 3 chargers, which only take 30 minutes to fill up a car battery. The city has installed some fast chargers at municipal parking lots, and the former moped rental company, Revel, has built an off-street charging “superhub” in Brooklyn.

Transportation accounts for nearly 30 percent of New York City’s greenhouse gas emissions — second only to building emissions — and more than 80 percent of that is from passenger vehicles, according to DOT.

City officials have pushed electric vehicles to help reach a goal of carbon neutrality by 2050, echoing similar efforts by Gov. Hochul at the state level and the Biden administration to bankroll EV infrastructure.

EVs may have zero tailpipe emissions, but like regular cars, they do nothing to solve America’s crisis of car dependence and road violence, which is actually made worse because the battery-powered vehicles tend to be heavier.

Even as it rolls out the electron carpet for e-cars, the city has been very slow in supporting the recharging needs of far more sustainable forms of electric mobility, such as e-bikes and mopeds.

The Adams administration promised — but failed — to electrify at least two Citi Bike stations last year, and the city has been slow to roll out charging hubs for delivery workers. A project to bring charging stations to public housing developments that was slated to start late last year won’t actually go live until the end of this year, according to New York City Housing Authority officials.