The genre’s roots date back hundreds of years, to the prison cells and gallows of 17th-century London.

“There’s been 11 hardback books on me,” the serial killer John Wayne Gacy told a reporter on the eve of his execution in 1994. “Thirty-one paperbacks, two screenplays, one movie, one Off Broadway play, five songs and over 5,000 articles. What can I say about it?”

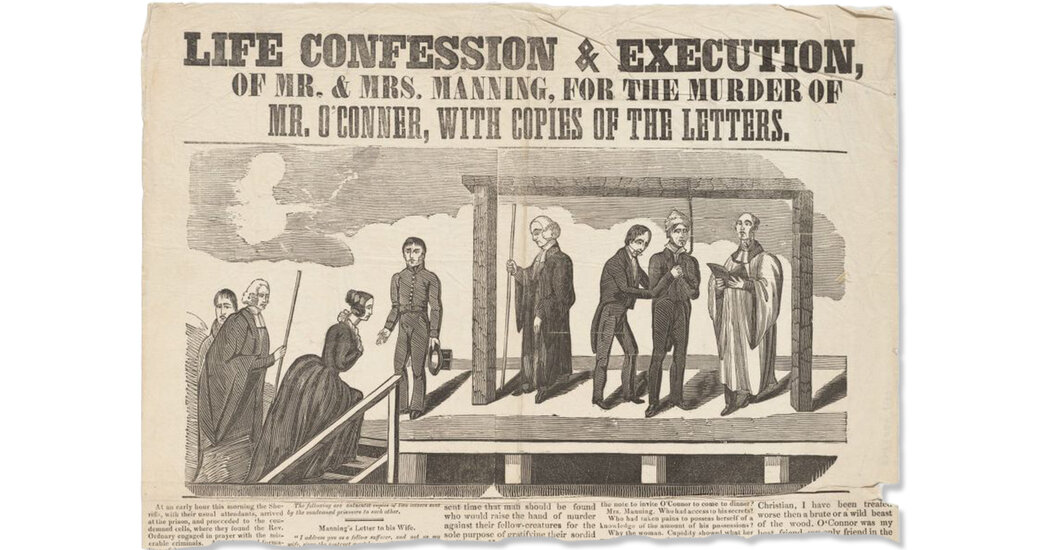

What can be said about it is that murder makes a lucrative story, something authors of the true crime genre have exploited in recent years to forge a multimillion-dollar industry, placing serial killers on our screens, funneling their voices into our ears, recounting their “exclusive” tell-alls in best-selling books. We may consider the obsession with true crime a contemporary preoccupation — with Etsy shops selling enamel pins of Ted Bundy’s face and his Volkswagen, and crime conventions filling casino-size hotels with teenage girls in “Murderino” T-shirts. But these grisly stories, and our insatiable thirst for them, have been monetized for hundreds of years.

Long before the self-styled Zodiac Killer mailed his letters to California newspapers, threatening killing sprees and bombings if his messages were not printed, there was an English prison chaplain named Henry Goodcole who bolstered his modest salary by selling stories about death and sin. Between 1620 and 1636 Goodcole served as “Ordinary,” or “Visitor,” at London’s notoriously lawless Newgate Prison, his job being to attend to the prisoners’ spiritual welfare — preaching, hearing confessions and leading services behind the thick, dank walls.

Newgate was rife with killers (as well as debtors and thieves) and, thus immersed in tales of blood and abomination, Goodcole saw a market opportunity. But how to make his money? Literacy was on the rise in England, and the political, social and religious upheaval of the 1600s meant the public was ravenous for information. Murder, Goodcole shrewdly realized, was among the stories they liked best.

So, the chaplain turned his hand to producing broadsides: cheaply printed prose pamphlets detailing the lives and crimes of the prison’s most dangerous inmates. The broadsides featured hyperbolic, often wildly embellished last confessions and “interviews” with the condemned, and for a long time Goodcole was one of the most eminent authors on the true crime scene.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.