Reading is always a revolutionary act. From banned books featuring queer characters in school libraries to censorship under the guise of abridgement, it is without a doubt that reading and writing are inherently powerful tools to our own liberation and self realization. These tools are important even more so in Virginia, as Virginia has one of the highest numbers of banned books in public schools and libraries, most of which tell stories of underrepresented groups in literature, like people of color, LGBTQ+ people, and immigrants. In line with harmful, decades old stereotypes, most LGBTQ+ books are banned due to supposed graphic sexual content or imagery, while heterosexual books with the same caliber of content are not seen as inappropriate for public schools or libraries. The crime to these critics is not the romance or love alone, but instead who the object of the romance or love is.

Even though public libraries are victims to book banning, libraries were and still are important meeting places for underrepresented people that may not have safe spaces elsewhere. Richmond Public Library became a popular meeting space for queer individuals, mainly the Richmond Gay and Lesbian Pride Coalition, an LGBTQ+ rights group formed in the late 1970’s within Richmond to promote equal rights. Within the Richmond Public Library, they would hold meetings, with topic of conversation ranging from discussing the finances and promotion of their main event, the Richmond Lesbian and Gay Pride Festival, to voting on board members, to compiling the “Gayellow Pages”. Even though they are not yet digitized, you can find archival meeting minutes, board candidacy personality write-ups, and more at VCU’s library archives here.

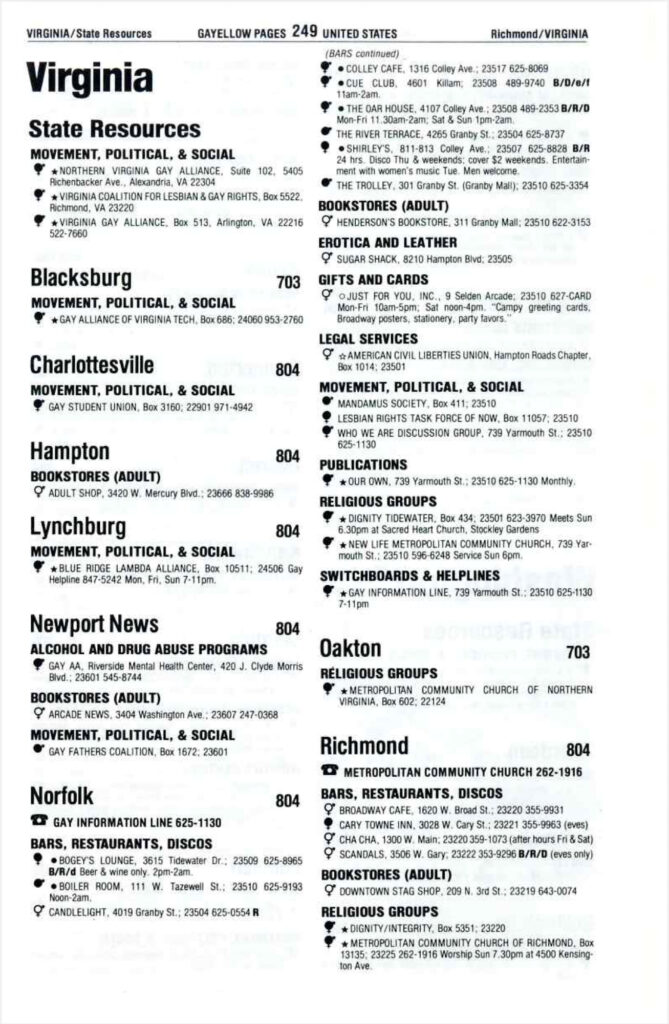

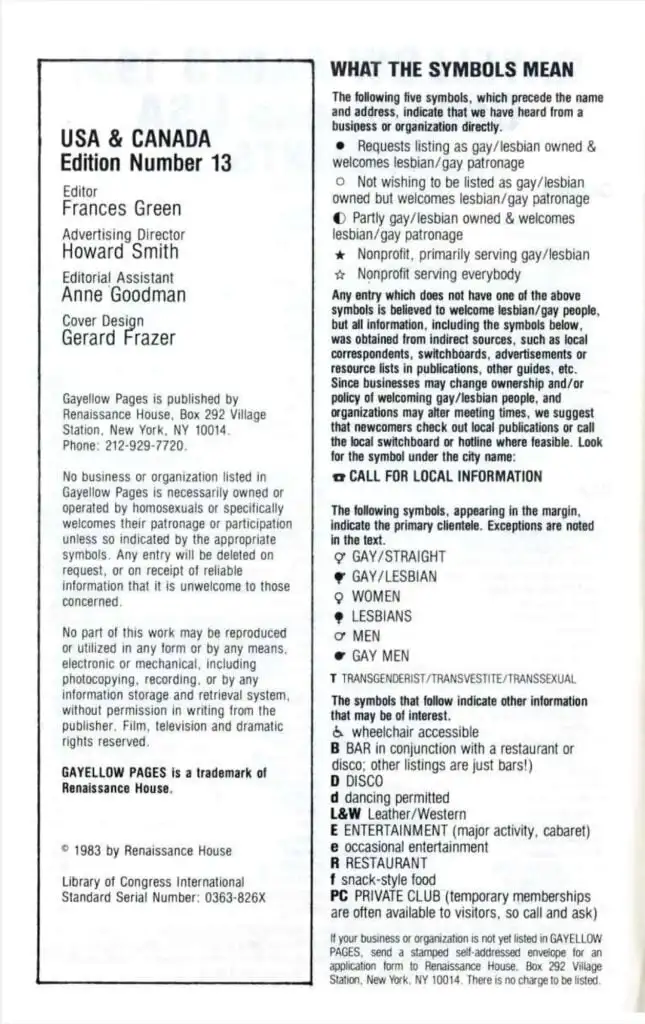

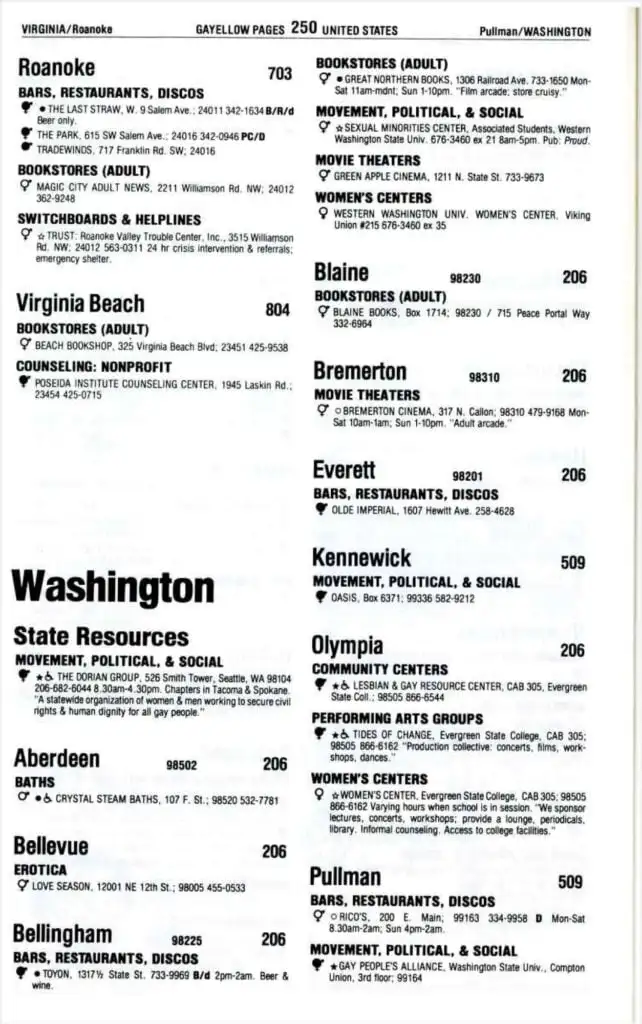

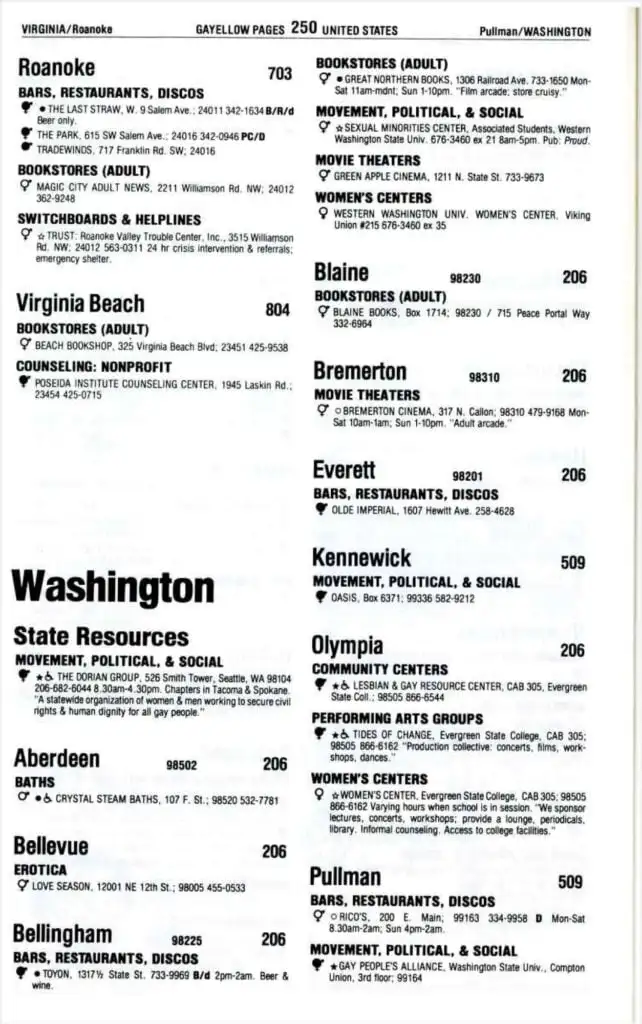

The Gayyellow Pages, a play on traditional “yellow pages” that would contain business locations and contact information, were a source of safety for LGBTQ+ people at the time. Below is an example of a different Gay Yellow pages book from 1984.

Archival Page of the “Gayellow Pages: The National Edition” (#13) Edited by Frances Green in 1984 featuring Virginia state locations open to LGBTQ+ guests, which can be accessed here.

These booklets would contain information concerning (but not limited to) unofficial meeting places, underground gay bars, or otherwise LGBTQ+ friendly spaces. Without the ability to read reviews online warning of transphobic staff, for example, the Gayellow Book in Richmond allowed for people, especially visitors and new residents, to know where it would be safe to go with a partner or alone as an openly queer person. Overlapping with other alternative lifestyles that are not explicitly queer, like the punk and goth scene that are still prominent in Richmond today, the Gayellow Pages offered places for people to see entertainment and socialize, such as drag performances at Godfrey’s or punk shows commonly held at Scandals.

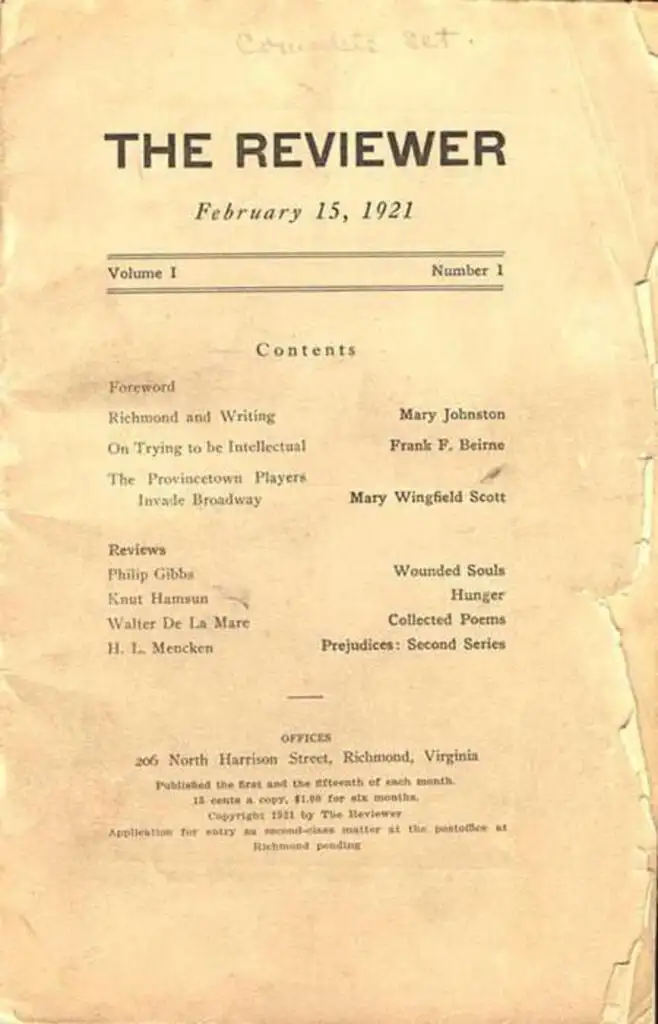

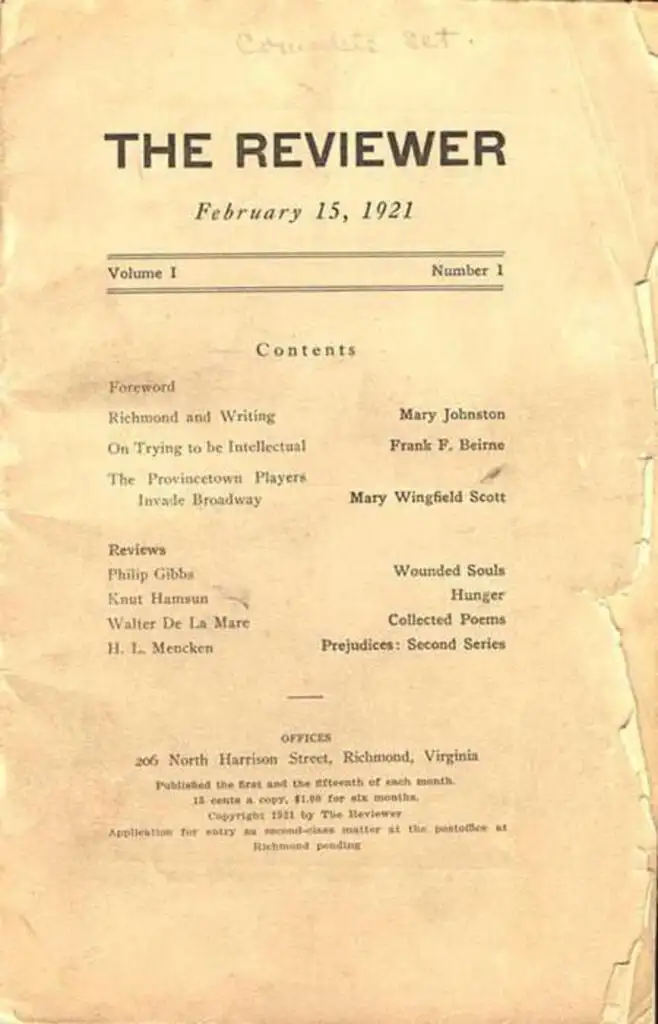

Although queer movements within Richmond gained traction in the late 20th century, queer resistance and livelihoods existed before these heightened times of growing queer visibility. Looking back to the early 1900’s, The Reviewer, published from 1921 to 1925, was edited by Hunter Stagg, a prominent literary critic and friend of many writers who was understood to be gay by both contemporaries and historians. Writing book reviews, mainly published within The Reviewer, Stagg managed to almost single handedly connect Richmond in the 1920’s to the writing world at large through his connections to writers from places across the nation, like New York, where the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing. Introduced to the Harlem Renaissance’s Langston Hughes, author and poet, through friend and popular writer Carl Van Vechten, Stagg famously held a party for Hughes at his home, featuring “Hard Daddy” cocktails – a reference to Langston Hughes’ poem of the same name four years prior. Without Hunter Stagg, Richmond may not have become the literary and cultural center that it is today.

Ellen Glasgow, born in Richmond in 1873, was an author, political activist, queer woman, and also an acquaintance of Hunter Stagg. During her career, Glasgow published 20 novels, as well as a collection of poems, a book of literary criticism, and a book of short stories. Writing of romance, relationships, the south during and before the Reconstruction Era, and class conflicts, Glasgow is hallmarked as the founder of “southern realism” in literature, a genre used by many writers after her, like the better known William Faulkner. Although having many relationships with men, she never married. However, she did live with her secretary, Anne V. Bennett in a Main Street home in Richmond until her death in 1945.

At the time, living with a “roommate” (read companion) was not necessarily frowned upon, however it was not commonplace the way that it is today. It would have definitely been considered outside of the norm of the time to live with the same gender, especially considering that neither of these women were married or widowed, however due to her status and business relationship with Bennett, they were not subject to much scrutiny, and in fact, her literary work was critically acclaimed at the time she was writing.

Within the same time period, Grace Arents, the niece of Lewis Ginter – a business man dealing tobacco who lived for most of his life with John Pope, a “business partner” – was another prominent queer woman. A wonderful philanthropist, Arents grew vegetables in her garden to donate to sickly youth and used the money inherited from Lewis Ginter to create foundations for schools and churches that still exist today, like the Grace Arents School, now called Open Highschool, and the Lewis Ginter Community Building in Ginter Park. Arents lived with Mary Garland Smith in the Bloemendaal House that still currently stands at Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden in Richmond from the early 1910’s to her death in the late 1920’s. She was extremely shy, with only a few photographs existing of her, but it is known that she was an avid reader and gardener.

After her death, she ordered to have her diary and personal correspondences be destroyed as well. After Arents death, Mary Garland Smith remained on the property in their home – it was written in Arents’ will that Smith was to be granted lifetime rights to the Bloemendaal House and the attached acreage. After Mary Garland Smith’s death, however, the land was to be given to Richmond City to create a botanical garden with the name sake of her uncle, Lewis Ginter. Even though Arents was not a writer herself, her financial contributions for the establishment of schools and libraries had a major impact upon the literary world of Richmond and the next generation of writers.

Today, there is still an extremely active LGBTQ+ community in Richmond, but thankfully, one that does not need to operate under the posture of “business partners” or same sex “companionship” anymore. Even so, there are still many barriers for queer people that exist within Virginia, especially for transgender and genderqueer people. With that said, with the invention of the internet and social media, it is much easier to assess the safety of businesses for openly queer people, generally removing the need for publications like the Gayellow Pages in modern times. Even so, without these foundational people and publications of history, whether they are from the 1970’s or the 1870’s, Richmond would not be the way that it is today.

Next time you pass Richmond Public Library, Open High, or Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden, make sure to thank the generations of queer people that walked by the exact same place and those that began the arduous journey towards queer acceptance.